The Koreshan Unity

Followers

Becoming Koreshan

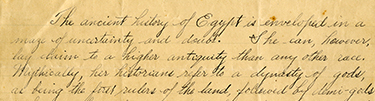

The impetus of Cyrus Teed’s Koreshanity can be traced to his illumination, when Teed experienced a vision of a woman while alone in his laboratory. This woman conveyed a set of truths, which formed the basis of Koreshanity. Though the catalyst for Koreshanity centered on an introspective experience, its success required the exact opposite. Teed studied, communicated with, and visited various other religious groups, and eventually gained followers of his own.

His following grew as he lectured throughout New York State and in San Francisco and Chicago, though it was not limited to these locations. Newspapers reported on Teed’s beliefs, attracting the attention of men and women throughout the country. Teed garnered support, converted many to Koreshanity, and established the College of Life and his Chicago-based commune in 1886 and 1888, respectively. Multiple stages of membership existed for prospective Koreshans. Initially, applicants entered a probationary period with the Unity in order to explore the lifestyle and determine his or her future level of participation.

Working Together

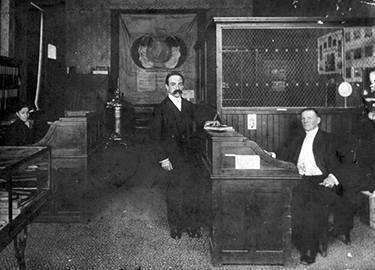

Much of Koreshanity’s success can be attributed to work completed by Teed’s followers. Each member had a role within the Unity from its initial stages in San Francisco and Chicago to its settlement and growth in Estero, Florida. Responsibilities ranged from cooking and household work to the management of finances, farming, and printing. Gender did not determine a member’s place within the Unity; individual skills and interests drove labor assignments. Despite moving to an undeveloped portion of Southwest Florida that required a large amount of effort to create livable conditions, members found time for leisure and entertainment. Together, Koreshans established a community rich in culture, religion and education.

Though membership rose and fell throughout the years, a number of prominent members devoted their lives to the Koreshan Unity. Life outside of the administrative realm of the Koreshan Unity was captured in the manuscripts of these Koreshans. At the Unity’s height, it is estimated that there were upwards of 200 members in Estero. Many individuals and families shaped the history of the Koreshan Unity, but only a portion of their records remain within the Koreshan Unity Papers. What follows is a glimpse into the Koreshan lifestyle as documented in the existing records within the Andrews, Silverfriend, Bubbett, Rahn and Michel member files.

Andrews

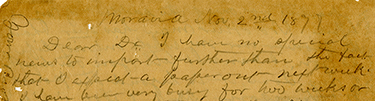

Considered one of the earliest followers of Teed, Dr. Abiel W.K. Andrews and his wife Virginia were instrumental in the Koreshan Movement. Abiel Andrews acted as an early collaborator and editor of Teed’s manuscripts and publications, often discussing beliefs and theories at length. Abiel provided Teed with additional insight into daily and spiritual life.

While Abiel’s death in 1891 prevented him from assisting Teed in his Estero years, the same cannot be said for Mrs. Andrews. Virginia devoted a large part of her life to Teed’s work in Chicago and Estero. A member of the Planetary Court and Koreshan Unity Secretary, Virginia partnered with other Koreshans to maintain Unity operations. Perhaps the most important contribution can be found within her journal, where she wrote on the day-to-day life of the Koreshans in Chicago.

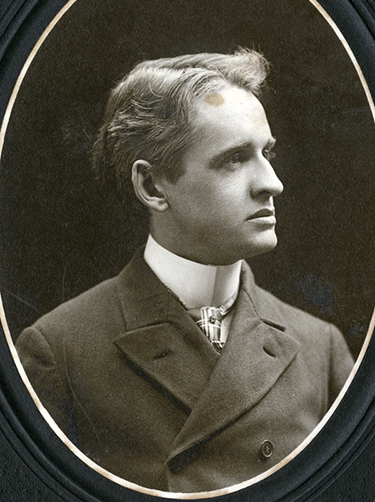

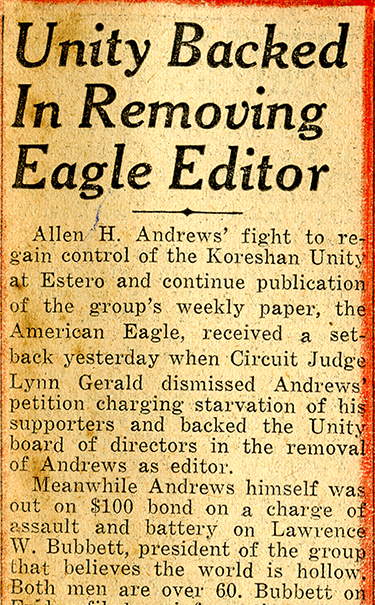

Abiel and Virginia Andrews had four children. Three of the four made the trip with Virginia to Estero in 1894, but only one of the children remained a Koreshan into adulthood. Growing up in the Unity, Allen Andrews received years of training at the Guiding Star Publishing House. He eventually became the editor of The American Eagle, and the Unity’s President from 1929-1949. Relations between Andrews and new Koreshan leadership deteriorated in later years, culminating in a court case. The Koreshan infighting garnered quite a bit of publicity in the local Fort Myers newspapers.

Silverfriend

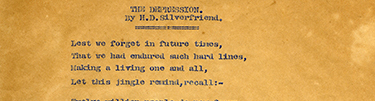

Joining in 1888, both Henry D. and Henrietta “Etta” Silverfriend were charter members of the Koreshan Unity. The brother and sister pair served as board members for most, if not all, of their tenure as Koreshans and lived in the Planetary Court from its inception in 1904. Though the Court was intended as housing for the Seven Sisters, or managerial staff, of the Unity, Henry served as a male protector of sorts for the women.

Etta held the position of Treasurer, Manager of The Flaming Sword, member of the Sisters of the Planetary Court, and caregiver. Records show that she was well respected within the Unity and that Teed often valued her opinion above all others. A devout Koreshan until her death in 1944, Etta was buried alongside fellow Koreshans in their private cemetery.

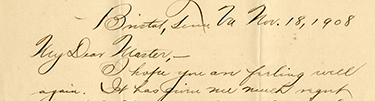

Henry assisted Teed with his business ventures and lectures, often traveling around the country to gain additional followers. He assisted with the Bristol Manufacturing Plant in Tennessee and the Koreshan Cooperative in Washington, D.C. and acted as a Koreshan diplomat to the Harmonists in Economy, Pennsylvania. Though the Plant and Cooperative would eventually be sold and deemed a failure and relations with the Economy Harmonists broke down, it was not for Silverfriend’s lack of effort, which is apparent in his correspondence.

Bubbett

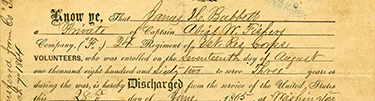

Though the Bubbett family originated in Western Pennsylvania, it was a lecture in Chicago in September of 1886 that first converted Evelyn Bubbett to Teed’s cause. Her husband, James H. Bubbett, a Civil War veteran and participant at Gettysburg, agreed with Koreshan doctrine. Both began work for Teed in 1887, assisting with the publication of The Guiding Star. The couple, along with their three children, moved first to the newly acquired communal home in Chicago in 1888, and later to Estero in 1894. As a Sister of the Planetary Court, Evelyn lodged with the other six sisters and Henry Silverfriend. James took up residence at the Founders House with Teed. Evelyn and James served on the Board of Directors; Evelyn served as Treasurer and James as Chairman. James went on to serve as Unity President from 1909 until his death in 1924.

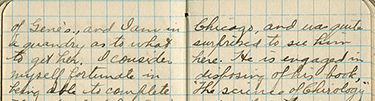

While the three Bubbett children, LeRoy, Imogene, and Laurence, grew up in the Koreshan faith, they did not remain devout lifelong members. With both parents active in the Guiding Star Publishing House and the Unity’s strong belief in the education and training of children and young adults, LeRoy, Imogene, and Laurence became skilled at trades. The Bubbett sons worked in Baltimore, Chicago, and New York as printers. LeRoy started a family of his own and remained in the North until his death in 1936. Imogene left the Unity to marry Claude Rahn, a childhood friend and one-time Koreshan, in 1913.

Later in life, Laurence went back to Florida to work in Miami. In the 1940s he returned to the Koreshan Unity and took up work at the Print Shop. In 1947 he was elected President of the Unity. He worked to restore the Unity grounds with the assistance of the remaining members.

Rahn

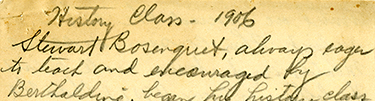

In 1906, Claude Rahn traveled from Baltimore, Maryland to Fort Myers along with his father and grandmother, Henry N. and Elizabeth Rahn, to meet Dr. Teed. Despite his father and grandmother’s eventual return to Baltimore, Claude remained at the Unity where he would spend the next five years. In 1912, with the blessing of those in charge of the Unity, Rahn left Estero to work initially at a New York City publishing house and later for the E.B. Kelley Company of New York. He continued to value both the Koreshans and their beliefs, marrying Imogene Bubbett in 1913. Claude and Imogene lived in Brooklyn, New York until the stock market crashed in 1929 and prompted a move first to Tampa and later back to Estero, Florida.

Even with Imogene’s early death in 1932 and his sporadic relocations between the Northeast and Florida, Claude persevered, eventually remarried, and had continued success in his business ventures. Rahn served as a Board Member for many years, as Secretary beginning in 1933, and as Vice President for a short time after Laurence Bubbett’s death in 1960, until officers were able to be elected. Rahn gave great care and placed a high level of importance on the history of the Koreshan Unity. He composed many manuscripts on the institutional history of the Unity as well as its members. In August of 1973, at the age of 88, Rahn suffered a major heart attack and passed away.

Michel

Hedwig Michel, a German Jew, came to the United States from Germany in 1940 in order to escape Nazi persecution. Since the vast majority of her property was lost in transit, she arrived in Estero with few material possessions. She made up for this, however, with an exceptional work ethic, a deep interest in cellular cosmogony, and extensive experience as secretary and headmistress of a Frankfurt-based boarding school.

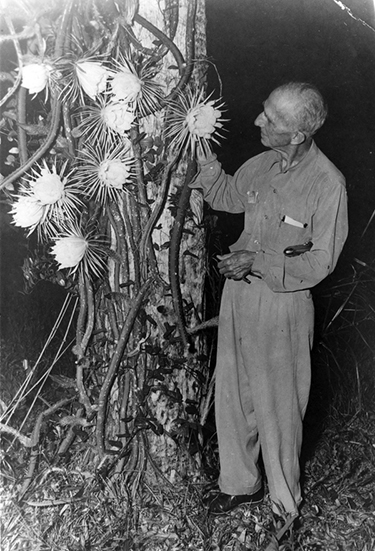

From 1940 until her death in 1982, Michel worked as a custodian for the Unity’s trailer park, caregiver to many aging Koreshans, manager of the general store, editor of The American Eagle, as well as a Unity board member, Treasurer, and President. Outside of her Koreshan work, Michel participated in various organizations ranging from her work as an active member of The American Red Cross and Fort Myers News-Press to various Florida-based garden clubs, the National and Florida Nature Conservancy, and the National Audubon Society.

Officially entering the Ecclesia of the Koreshan Unity in 1944, Hedwig became known as the “Last Koreshan.” Just like many Koreshans before her, she recognized the importance of their Estero settlement. Both Michel’s resolve and purpose are apparent in a letter written to Division of Recreation and Parks Director Ney Landrum in 1976: “Some time ago...I had made a vow to do whatever asked of me for a country and his people who made it possible for those in despair to find a new homeland, that I would devote all I had to give without receiving a reward. I found in The Koreshan Unity the mission for my life work, complete fulfillment.”

In order to ensure its protection and place within Florida’s history, Michel, with the help of Rahn, Bubbett, and countless others, worked to secure a state park on Koreshan grounds. In 1967, the Koreshan State Park was dedicated and ensured the preservation of almost a century of work.

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program