The Koreshan Unity

Legacy

A New Purpose

As the most active period of a community or organization ends, a partial change in business practice occurs. Efforts previously centered on attracting members shift towards a need to safeguard its established history. Perhaps it’s the group’s legacy that most definitively decides the level of success achieved. It is, after all, through this legacy that the current generation determines the success of past generations; a retrospective selection. Regardless of the ways and means, the Koreshan Unity most assuredly left a legacy. This is most obvious at the Koreshan State Historic Site in Estero. The legacy retained in the Koreshan State Historic Site is due in large part to the work of Hedwig Michel and the support from her fellow Koreshans: Laurence Bubbett, Vesta Newcomb, Conrad Schlender, and Alfred Christensen. Beyond the Unity, the Koreshans benefited from assistance given by their attorney, Parker Holt, and friend and long-time ally, Claude Rahn.

The decades following Cyrus Teed’s death were those of slow decline for the remaining Koreshans. This abatement affected more than just membership; both Unity grounds and buildings were in serious need of repair. Bubbett and Michel, Unity President and Secretary, respectively, were cognizant of the less than desirable state of their homestead. In an effort to finance repairs and maintenance of the site, Michel sought out World War II reparations owed to her from Germany. Michel was successful in securing her dues, and set to work with renewed confidence.

Michel’s war reparations helped the Unity immensely. By loaning much of her personal money, Hedwig prevented the Unity from having to apply for outside loans. Once Unity funds were available, Michel was reimbursed for most, if not all, of the advance. Together, the remaining Koreshans were able to attend to the ever-growing building maintenance list as well as the general upkeep of the surrounding gardens, paths, and outdoor recreation areas. Michel knew, however, that this supplementary income was finite. Once the severe dwindling of both membership and funds took full effect, the Unity risked extinction.

State Park

Though the Unity owned a substantial amount of land in the Estero area, there was an ever-present risk of it falling into the wrong hands in the future. Michel and Bubbett were opposed to the possibility of the sale and wide-spread commercial development of Unity grounds. In an effort to preserve the Koreshan legacy, Michel looked to the State for collaboration. A devout member of several Florida-based and national environmental organizations, Michel was familiar with the assistance afforded if a portion of Koreshan land was admitted into the state park system.

Official discussions about the future of the grounds began on February 1, 1952, at a Koreshan Board of Directors Meeting. Here, initial ideas were discussed and a resolution adopted to make certain that the topic remained at the forefront of the Unity’s agenda. In 1956, the Board made a proposal to the State of Florida that outlined the historical value of the Koreshan land. Governor LeRoy Collins was receptive to the proposal and responded favorably, noting the current lack of a state park in the Lee County area.

While early communications were encouraging, interest fizzled in the late 1950s. Rahn, in his manuscript titled “A Brief Outline of the Life of Dr. Cyrus R. Teed (Koresh) and of the Koreshan Unity,” points to Bubbett’s death in 1960 as the cause for a renewed push for the long-term preservation of Koreshan terrain. After taking the Unity Presidency, Michel continued to devote her time towards an agreement with the State of Florida.

In 1961, after years of collaboration, the Unity deeded approximately 300 acres to the State of Florida. This “Gift to the People,” as Hedwig deemed it, aligned with Koreshanity’s fundamental values of education, environmentalism, and preservation. As Florida’s 36th state park, the site’s continued maintenance was ensured by the four remaining Koreshans in perpetuity.

Plans for the development of the site prior to its official opening took a few years to complete. With monetary assistance from the Florida Federation of Garden Clubs, a historic marker from the Florida Board of Parks and Historic Memorials was presented in 1963. Then, on Saturday April 8, 1967, the Koreshan State Park dedication ceremony commenced. In keeping with Koreshan event traditions, the ceremony was a social affair that brought entertainment, food, and many friends and supporters to Estero.

Beyond the State

Concurrent with the donation of Koreshan land to the State, the Unity collaborated with the Nature Conservancy. In 1966, 75 wooded acres of Koreshan land was donated to the Conservancy with plans to create a nature preserve. In 1976, the Koreshan State Historic District was added to the National Register. In addition to joint projects, the Unity pulled their resources together internally. Plans for a new Koreshan building began in 1971. Completed in 1980, the College of Life Building would eventually house a Foundation of the same name.

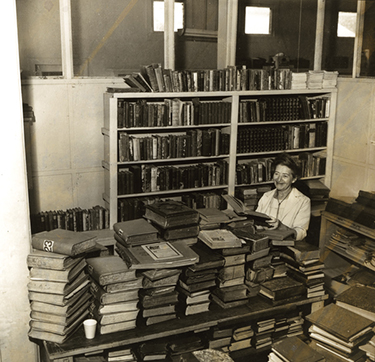

In 1972, the Unity incorporated the Pioneer Education Foundation in Florida, a non-profit offshoot of the Koreshan Unity primarily dedicated to services that promote lifelong learning. The organization was also designed to oversee remaining Koreshan property, stocks and other holdings. The Pioneer Education Foundation and future College of Life Foundation proved to be another avenue for the protection of Koreshan assets separate from the State owned and controlled parcel. A library, reading room, and space for the Unity’s expansive archival holdings were included in the building to facilitate Pioneer Education Foundation aims. Once it was completed in late 1979, the Estero and Fort Myers communities visited the College of Life building where they enjoyed various educational events.

Another Imprint

Though the Koreshan State Historic Site preserves much of the Koreshan legacy, it does not end there. Part of the Koreshan legacy rests in the records left behind. The fact that the Koreshan Unity Papers exist is in large part due to the work of the Koreshans. From the beginning, they saw the importance of the long-term preservation of their work. A portion of the manuscripts, correspondence, photographs, and other Koreshan documents housed at the State Archives of Florida were created during the Chicago years. They survived the trip to Estero, where they faced extreme environmental concerns and remained to form the foundation of the extensive Koreshan Unity archives. In a largely undeveloped area, poor living conditions worsened the existing threat from heat, humidity, and insects. While some damage is captured on the Chicago and Estero-based records themselves, their current condition is much better than might have been expected.

The Koreshan Unity Papers housed in Tallahassee, along with those that remain at the Koreshan State Historic Site in Estero, provide users with the chance to explore Koreshan history via primary sources. It is through this documentary legacy that the Koreshan Unity most assuredly will endure.

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program