The Koreshan Unity

Spreading the Word

- Support, Sustained

- On Their Soapbox

- Publications

- Satellite Branches

- Paradise Found and Lost

- The Social Side

Support, Sustained

The long-term success of any organization, group, or business is contingent upon a myriad of factors. Among these are outreach programs designed to strengthen and attract support from within the group and its surrounding community. This awareness shapes public perception and ensures its place in history.

The Koreshan Unity employed various outreach tactics over the years. As membership grew and then dwindled, the focus of the group changed. Each transition period required an alteration in advocacy efforts. This section centers on three Koreshan Unity outreach activities: evangelism, publishing, and community events. Each enterprise sought to propagate Unity opinions and religious beliefs as well as to emphasize its cultural significance.

Lectures given by Cyrus Teed and other key Koreshans, Unity publications and literature, and annual events were an integral part of Koreshan life. Impact beyond the Unity itself is visible in the history of the development of Southwest Florida. Outreach benefited Koreshans as well as Florida’s citizens and environment.

On Their Soapbox

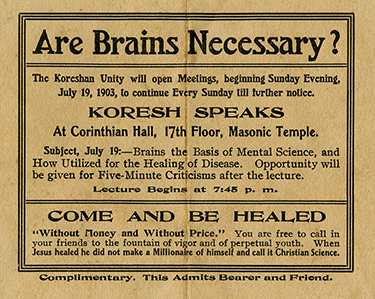

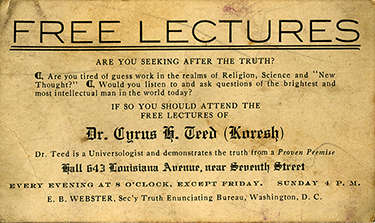

As the leader and creator of Koreshanity, Cyrus Teed lectured extensively to advocate for his religious beliefs. A charismatic orator, Dr. Teed’s lectures attracted a great number of attendees. Through these lectures Teed discussed his views on science, religion, and his personal relationship with God as a result of his illumination. While his early lectures had adverse affects on his local medical practice, they eventually proved successful in attracting spiritual followers.

In 1886 Teed received the honor of speaking at the National Association of Mental Science Convention in Chicago. Time spent expounding beliefs at the Chicago conference was arguably the most fortuitous of his career. Here, Teed found a receptive audience, eager to listen and discuss. Many of Teed’s early followers pointed to his lectures as the catalyst for their acceptance of Koreshanity. In addition to formal addresses to the outside community, Teed gave frequent informal talks to Koreshans. From the member files of the Koreshan Unity Papers, it is clear that these intimate lectures were prized memories for the Koreshans.

As membership flourished, Teed’s followers took on lecturing responsibilities. The most notable of the traveling lecturers was Henry Silverfriend. Traveling across the country, Silverfriend discussed Koreshan doctrine and cultivated relationships with other communal societies on behalf of Teed.

Dissension amongst the Koreshans following Teed’s death interrupted the Unity’s routine. Once an essential part of Koreshan activities, lecturing for religious purposes ceased. Eventually the outreach technique was used again, though its new purpose was not to gain followers, but to educate listeners on Koreshan history.

Publications

This section provides a brief overview of Koreshan publishing operations from the 1880s to the late 20th century. For more information, see Irvin D.S. Winsboro, “The Koreshan Communitarians’ Papers and Publications in Estero, 1884-1963,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 83:2 (2004): 173-190.

Cyrus Teed was a tireless promoter of Koreshan beliefs. In addition to regular lectures, the most successful vehicles for disseminating information about the Unity were the numerous publications printed. The Koreshans produced more than 35 publications between the 1880s and the late 20th century, ranging from placards and pamphlets to weekly newspapers and books.

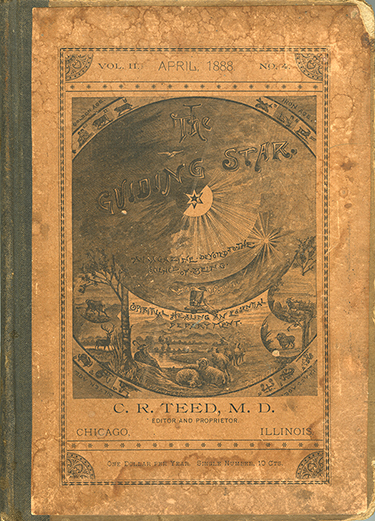

Koreshan publishing began in Chicago on December 1, 1886 with The Guiding Star. Initially published by the Koreshan-owned Daily Englewood Company, The Guiding Star focused on faith healing.

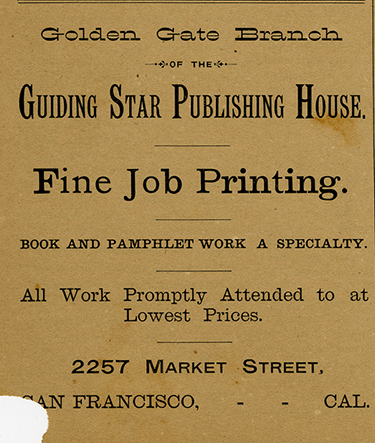

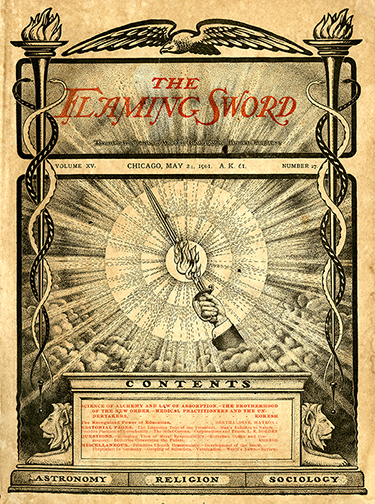

In 1888, the Koreshans founded Guiding Star Publishing House, which supplanted the Daily Englewood Company. The Guiding Star ceased publication in May 1889 and was replaced with The Flaming Sword on November 30, 1889. The Flaming Sword went on to become one of the longest running Koreshan publications and Teed personally authored many of the lead articles. In addition to publishing their own literature, the Koreshans solicited outside contracts for custom printing jobs.

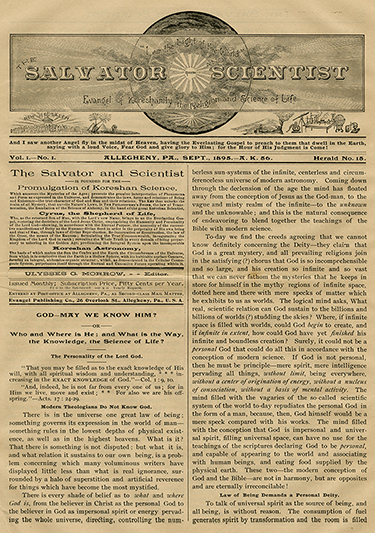

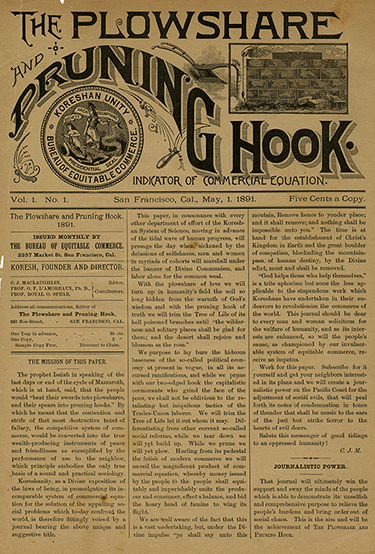

Satellite Branches

Satellite Koreshan communities in San Francisco and Allegheny, Pennsylvania, published their own literature. The San Francisco contingent published The Plowshare and Pruning Hook from May to November 1891. The Plowshare and Pruning Hook focused on labor issues. The Allegheny community published The Salvator and Scientist, which detailed Teed’s “hollow earth” theory. Both publications eventually moved to Chicago and were phased out.

Paradise Found and Lost

In 1903, publishing operations moved to the newly established settlement in Estero, Florida. Printing equipment arrived from Chicago and was assembled. The Koreshans built a two-story printing house of heart pine harvested from their property along the Estero River. Once installed, Koreshan operations rivaled any commercial printing house in Florida. From the final years in Chicago through the move to Estero, Koreshan publishing shifted its focus from Koreshanity to the secular manifestation of these beliefs in the form of rights for labor, women and minorities.

The workforce behind Koreshan publishing revealed the progressive nature of some of their beliefs. According to historian Irvin D.S. Winsboro, women made up about 40% of workers employed in Koreshan publishing. In comparison, women constituted roughly 15% of the industry in Florida as a whole. The opportunity for women to find work in printing made the Koreshans exceptional in relation to their neighbors on the issue of women in industry.

The events of October 1906 changed the course of Koreshan publishing. On October 13, Cyrus Teed and other Unity members were attacked by their political rivals in Fort Myers while in town on business. Teed suffered permanent health problems from his injuries and died in 1908.

In response to confrontations before and after the brawl in Fort Myers, the Koreshans launched The American Eagle, the longest lasting and farthest reaching of their publications. Also in 1906, The Flaming Sword transitioned from a weekly to a monthly paper, but doubled in size from 14 to 28 pages. After Teed’s death, Unity members continued publishing The Flaming Sword on an infrequent basis, but maintained regular issues of The American Eagle.

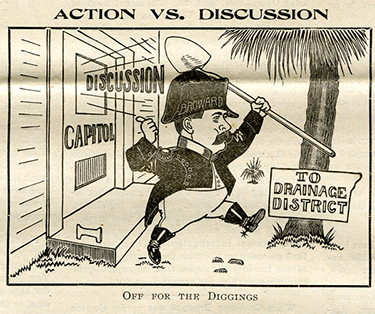

The American Eagle initially served as the organ of the Progressive Liberty Party, a political party formed by the Koreshans to counter Lee County’s Democratic Party. The American Eagle carried stories on local and national issues and featured political cartoons and advertisements for local businesses. Some of the topics of regional significance covered in early issues of The American Eagle included Everglades drainage and construction on the Tamiami Trail. The American Eagle blended the desire of Unity members to express their opinions on pressing political issues with the archetypal symbols and language of Florida boosterism common at the turn of the 20th century.

Tragedy stuck the Koreshan Unity compound on February 15, 1949, when a fire destroyed the printing house and its contents. Along with machinery, official records and print jobs were consumed by the blaze. The Flaming Sword never resumed publication. The American Eagle returned in 1965, but because the Unity lacked the funds to reconstruct their publishing operations it had to be done on the outside.

The publications of the Koreshan Unity represent an interesting chapter in the story of the utopian community. Despite the challenges of the frontier, the organization managed to produce and maintain high quality printing on a variety of topics. The collective works of the Koreshans provide insight into the ideologies of members as well as glimpses into an important period in Florida history.

The Social Side

The Koreshan Unity placed great importance on the social aspects of communal living. From the early years in Chicago, to the pioneer days in Estero and through the Presidency of Hedwig Michel, the Koreshans hosted numerous events. The local community was invited to many of these Koreshan festivals, especially those held in later years when few Koreshans remained. Some were scheduled around a time of religious importance to the Koreshans while others fluctuated depending upon cultural events during the year.

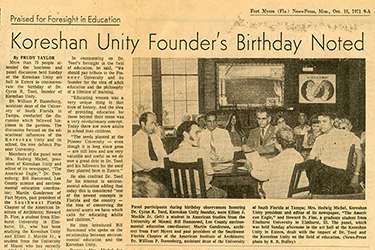

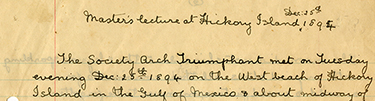

The most widely known of these events were the Solar and Lunar Festivals. The Solar Festival commemorated Cyrus Teed’s birthday (October 18, 1839) and was held yearly in mid-October. Members were entertained in various ways. Theatrical and musical performances by fellow Koreshans highlighted a combination of original and mainstream works. The recitation of Koreshan student compositions, food, fun, games, and souvenir awards ensued. In the early years, members could expect an address from Koresh based upon both current events in the community and religious teachings.

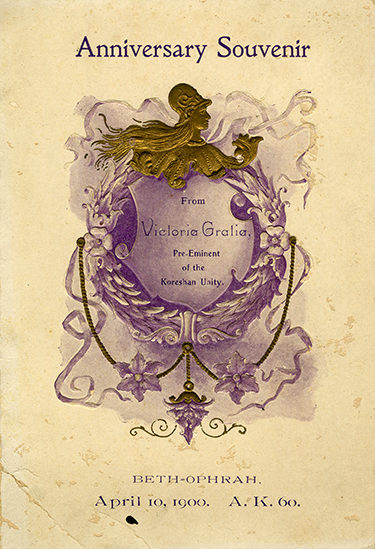

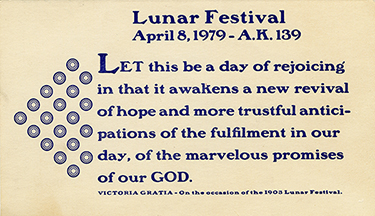

The lesser known of the two events was the Lunar Festival. Celebrated in the same fashion as the Solar Festival, this mid-April gathering marked the birth of Annie G. Ordway. Ordway, one of the earliest followers of Koresh, served as the first President of the Koreshan Unity. She operated as Teed’s counterpart in the managerial and supervisory sense, and in 1891 Teed pronounced her Victoria Gratia, Pre-Eminent of the Koreshan Unity. He believed Victoria embodied the female version of God and was, therefore, destined to be his successor. Despite Teed’s overwhelming faith in Victoria, not all Koreshans were convinced. After Teed’s death, many opposed Victoria’s continued leadership. This led to a discontinuation of the annual Lunar Festival, though some members did celebrate it sporadically in following years.

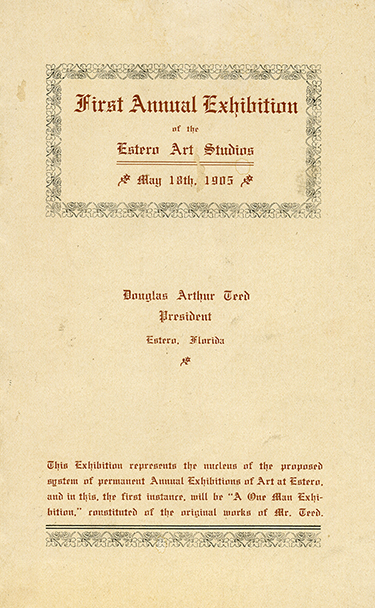

Along with the Solar and Lunar Festivals, the Koreshan community held an additional assortment of events in Estero. For example, they organized an Industrial and Art Exhibit for the general public beginning in 1905. The event first sought to display the various works of Koresh’s son, Douglas Arthur Teed, and eventually progressed to a general program of art, music, and dramatic entertainment. The Koreshan education system provided many extracurricular activities. Commencement exercises, holiday programs, and curriculum-related gatherings offered recreation for Unity members.

Following the Estero site’s admittance to the State Park system, event plans expanded in order to incorporate environmental activities as well as elements of Koreshan history and education. Attendees were invited on boat rides along the Estero River and enjoyed tours of the settlement and re-enactments of the Unity’s early pioneer life.

Beyond Koreshan inspired and coordinated proceedings, surrounding communities also began to use Unity grounds for local events. The Fort Myers and Estero Garden Clubs made frequent trips there to study and discuss horticulture. The state park attracted school field trips and even hosted a wedding. Through it all, Unity members, volunteers, and local supporters continued to strive for improved celebrations. The value placed upon community outreach encompassed both the early and later years of Koreshan life. Its continued importance is testament to the social and cultural traditions of the greater Fort Myers area.

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program