The Koreshan Unity

Building a Utopia

- The Koreshan Unity in Estero

- Koreshans at Work

- Boats, Bees and Building

- Cashing In

- Brawl in Fort Myers

- A New Era

The Koreshan Unity in Estero

In late December 1893, Koreshan Unity founder and messiah Cyrus Teed and an entourage of his closest followers returned to Southwest Florida. A trip to the area earlier that month had failed to yield what they sought most: land on which to build New Jerusalem, a community that would become the physical manifestation of Koreshanity.

Teed and the Koreshan Unity were familiar with relocation. After emerging from the ashes of the Burned-Over District in central and western New York State in the 1880s, Teed found a foothold in Chicago and began publishing The Guiding Star, the first of several Koreshan publications. By 1893, the Koreshan Unity counted more than 120 members, most living in the communal estate known as Beth-Ophrah. Wherever Cyrus Teed went he attracted both followers and detractors. Koresh, as he was known to his adherents, realized the need to find a haven far from his critics.

The first trip to Florida in early December 1893 was not without consequence. Teed met with a Mr. Whitehead who offered to sell land on Pine Island to the Koreshan Unity. The price—$150,000—was too high and the contingent returned to Chicago. Before Teed left he conducted a series of lectures and distributed pamphlets. One of the tracts landed in the hands of a German immigrant named Gustave Damkohler.

Damkohler established a homestead on the Estero River in 1882. Although he did not hear Teed speak in person, Damkohler obtained Koreshan literature. He quickly became interested in the Unity and wrote Koreshan headquarters. After receiving promising correspondence from Damkohler, the determined Koresh returned to Florida with hopes of obtaining land on which to start a community.

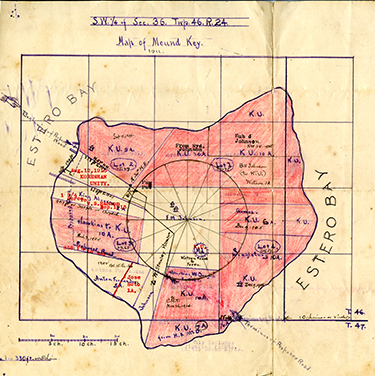

Damkohler sold most of his homestead to the Koreshan Unity shortly after they arrived in late December 1893. For $200 the Unity purchased 300 acres of undeveloped land along the Estero River. This turned out to be the first of many property acquisitions by the Koreshan Unity in Florida, and by 1907 they owned or controlled more than 6,000 acres in Lee County alone. Koreshan members migrated to Florida in waves over the next decade and put the land to work as Teed had imagined. Koresh did not promise a paradise in Estero, but “a pioneer life, one of strenuousity and sacrifice.” Unity members, most from affluent backgrounds, became “urban pioneers” on the South Florida frontier.

Koreshans at Work

Koreshan commerce and industry mirrored more established Florida communities. The Koreshans, unlike their neighbors, built a community on the principals of communal property and shared labor. Members did not receive cash payments, but exchanged labor credits earned for goods produced or purchased by the community. Shunning hourly wages in favor of community ownership and production was central to Teed’s economic philosophy. He hoped that Estero would serve as an example to the rest of the world and in time lure untold numbers away from the drudgery of industrialization.

Members started arriving on the Estero River in 1894, but the majority relocated from Chicago between 1903 and Teed’s death in 1908. Records from the early period of the Koreshan Unity in Florida reveal what the community achieved over a short period of time in a challenging environment.

Boats, Bees and Building

The earliest projects required clearing land for homes and agriculture. At first, community members lived in tents or thatched roof structures. In about 1895 the Koreshans purchased machinery for a sawmill. The sawmill was installed on the southern end of Estero Island. The sawmill and associated buildings on Estero Island burned in late December 1896, but were later rebuilt near the headwaters of the Estero River closer to the mainland settlement.

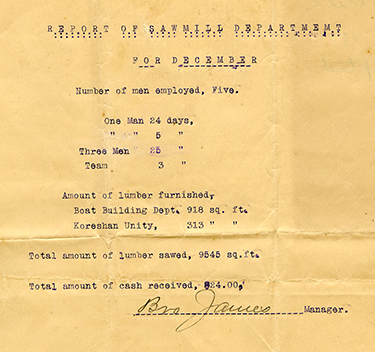

The sawmill report from December 1902 provides insight into early Koreshan industry. Like neighboring communities along the Florida frontier, the Koreshans’ proximity to bountiful forest products allowed their settlement to emerge seemingly overnight. In December 1902, the Sawmill Department reported a total of 9,545 square feet of lumber sawed. Of the lumber produced, 918 square feet went to the Boat Building Department and 313 to the Koreshan Unity. The remainder is not accounted for specifically in the report and at least some was probably sold to area residents.

The sawmill furnished cypress and pine for buildings on Koreshan land. Between 1895 and 1905 the Koreshans constructed several structures including a dining hall, bakery, two machine shops, and cottages for its members. In 1905, the Unity built the Art Hall, where they staged performances and community events. In addition to the arts and music, Teed practiced medicine on the grounds of the Unity and Koreshan members operated a school dubbed Pioneer University. People from the surrounding area came to Estero for education and medical treatment, in some cases the only such services available in the area.

The Koreshan Unity moved its printing operations from Chicago to Estero in 1903. The printing house, destroyed by fire in 1949, contained several large and small presses as well as paper cutting equipment. Only the successful Tampa and Jacksonville newspapers rivaled Koreshan publishing in the early 1900s.

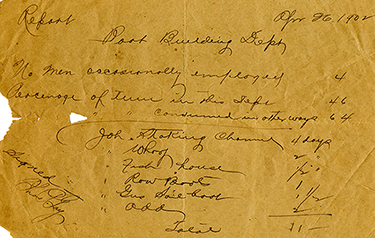

Boat building began on Estero Island soon after the sawmill was established. The accounting files of the Unity provide glimpses into Koreshan involvement in marine industries. In the document below, the Boat Building Department reported 11 days labor from four men “occasionally employed” in construction and repair work in November 1902. Later reports from the department list the names of completed projects, including the schooner Success, the steamers Seminole and Victoria, and the launch Wolverine.

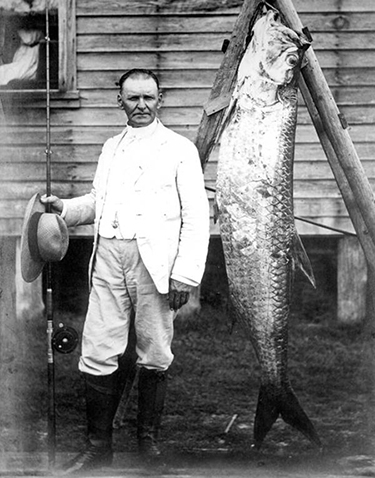

Subsistence and commercial fishing formed the backbone of many coastal towns in late 19th and early 20th century Florida. Koreshan properties were ideally positioned to take advantage of the thriving fish market in southwestern Florida, exactly as Teed had planned. In General Information Concerning Membership and its Obligations, Teed expounded on the role of waterways, the “greatest channels of international commerce,” in his vision of an ideal community.

Boat works and fishing were the initial steps towards Koreshan prominence in the region’s marine industries.

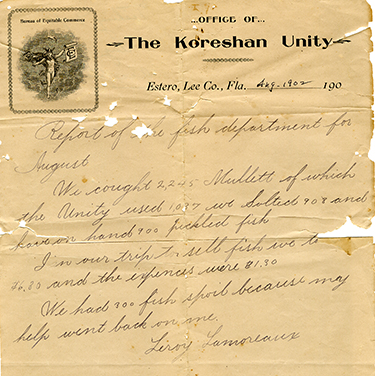

In August 1902, the Fish Department reported a hefty catch: “We cought [sic] 2,245 Mullett [sic] of which the Unity used 1,037 we Salted 908 and have on hand 900 pickled fish.” Koreshan involvement in the seafood industry also extended to sport fishing and harvesting turtles and shellfish such as oysters.

The Koreshans engaged in various agricultural pursuits at the main settlement on the Estero River as well as on parcels owned by the Unity throughout Lee County. From November 1901 to January 1902, Unity members worked a total of 250 days in agriculture. Noted on the Farm report for these months are three acres of “sugar cane planted” and 370 “gallons syrup made.”

The Koreshans also kept livestock and sold fruits and vegetables. The Unity became well known for their bakery, reportedly capable of producing 500-600 loaves per day. In the case of agriculture, livestock and the bakery, surplus items were sold for the benefit of the community. For example, in 1902 the Unity realized $43.22 for the “Sale of Hogs.”

Truck farming in Florida grew contemporaneously with the development of the Koreshan community. The expansion of rail lines into southern Florida allowed produce to be shipped northward during the winter months. Although the Koreshans appear to have consumed most of their fruits and vegetables, or sold them locally, they were part of the broader expansion of intensive agriculture in southern Florida.

Cashing In

The Koreshan Store, located just upriver from Bamboo Landing, sold dry goods and functioned like other general merchandise stores in Florida at the turn of the 20th century. The success of the store was directly tied to the expansion of transportation infrastructure in southern Florida. In 1902, “Cash sales in store” totaled $173.24; however, by 1916 the store reported sales of $18,539.43. The Tamiami Trail, completed in the late 1920s, ran directly through Koreshan property, which greatly increased visits by motorists. The Unity built a service station across from the store in 1926 to cater to the increased volume of travelers.

The “Itemized Report” of the Koreshan Unity for 1908 illustrates how far the community progressed from its inception in 1894. According to the report, land holdings in Estero amounted to $107,000 with improvements (buildings) worth $43,550. Other assets recorded, including the bee hives, livestock, water system, musical instruments and household goods, were valued at $17,350. The assets of the Unity totaled $259,873.50.

Brawl in Fort Myers

By 1906, with the bulk of the Unity relocated in Estero, the Koreshans ventured into local politics. In 1904, Teed sought incorporation for the town of Estero. Little opposition emerged among residents living nearest the Unity compound, but serious concern developed in Fort Myers, the seat of Lee County government.

Established Lee County politicians feared that incorporating Estero would divert local road tax revenues away from Fort Myers. Seeking to garner favor with Fort Myers politicians regarding the Koreshan situation, County Judge Philip Isaacs had the Estero election returns thrown out. This blatant disenfranchisement prompted the Koreshans to form their own political party, the Progressive Liberty Party (PLP), to oppose the Democrats in subsequent elections. The American Eagle became the voice of the PLP.

The Koreshan foray into politics angered the Democratic Party’s political machine in Lee County. Confrontations between local Democrats and the PLP turned to violence in October 1906 when Cyrus Teed and other Unity members were in Fort Myers on business. Teed was seriously injured in the melee and experienced permanent health problems until his death in 1908. Following the altercation, the Fort Myers News Press carried inflammatory editorials criticizing the Koreshans who responded in kind in the The American Eagle.

Historians of the Koreshan Unity trace the decline of the movement to the death of Cyrus Teed in 1908. Following Teed’s death, many members left Estero. Despite the drop in membership, the Koreshans continued to operate many of their economic ventures and hold community performances. The settlement entered a period of renewal with the arrival of Hedwig Michel in the 1940s.

A New Era

Michel, a refugee from Nazi Germany, helped revive the general store and the musical and theatrical performances characteristic of early Koreshan life in Estero. She also poured her energy into the trailer park operated by the Unity. In late 1979, Michel oversaw the completion of a new building to house Koreshan headquarters and the records produced by the Unity over the previous century. Michel passed away in 1982 as one of three women to serve as President of the Koreshan Unity.

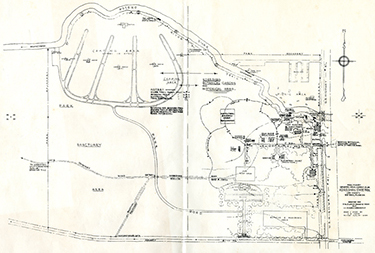

The State of Florida acquired most of the property held by the Koreshan Unity in 1961. Since that time, the Florida Park Service has operated the Koreshan State Historic Site. The park interprets Koreshan history with a focus on the life of Unity members on the Southwest Florida frontier. Programs at the park center on economic activities that flourished during the early days of the Koreshan Unity in Estero.

The Koreshan Unity achieved a great deal in their time on the Estero River. This is especially significant given the difficulties of life in southern Florida at the turn of the 20th century. The Koreshans persisted through internal divisions and external pressures and built a community founded on Cyrus Teed’s ideology of communal prosperity. Even though the New Jerusalem envisioned by Teed failed to materialize from the Florida swamp, the history of the Koreshan Unity provides important lessons on sustainability and the various ideologies wielded by pioneers as they confronted the Florida frontier.

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program