Florida in World War I

Floridians Who Fought Over There

Over 42,000 Floridians served in the Army, Marine Corps, Navy and Coast Guard during WWI. Though U.S. foreign policy mandated a neutral position during the first three years of the conflict, the country reacted to the specter of war with caution, steadily strengthening its defenses.

Soon after the Great War erupted in Europe during the summer of 1914, both the Florida Naval Militia and Florida National Guard saw enrollment increases. That same year, the United States Navy opened the nation’s first aeronautic training center, Naval Air Station Pensacola, where over 6,000 officers and enlistees would complete training by the war’s end in November 1918.

Despite moderate efforts at military preparedness, average civilians in Florida thought war was a distant possibility. However, rising German hostilities in early 1917 — aggressive submarine warfare and the publication of the Zimmerman telegram — signaled the increasing likelihood of war and propelled President Wilson to adopt a policy of armed neutrality. Floridians weighed in, and the majority of the state’s leading newspapers endorsed President Wilson’s move towards military engagement. Of the president’s actions, the St. Petersburg Daily Times pledged “the undivided loyalty of the American public.” The Miami Herald further concluded that “there [were] worse things for a nation than … armed conflict.” Other publications offered more measured responses. The Gainesville Daily Sun supported Wilson’s actions but held out hope that the country could “avert an open rupture with Germany.” The Madison Enterprise-Recorder further scrutinized U.S. diplomatic relations, observing that “we have been neutral in letter but not in spirit.” And in Estero, Florida, the Koreshan Unity, a utopian religious community, entirely rejected the prospect of becoming involved in the war. “Who will … show the way to a higher and nobler life, when this world war has completed its work of devastation and destruction?” cautioned the pacifist sect.

By April 1917, as unrestricted German submarine warfare continued to escalate, war seemed imminent. As a result, public opinion in Florida converged in support of full-fledged military action. On April 6, 1917, the overwhelming majority of the U.S. Congress, including Florida’s two senators and four representatives, voted to approve President Wilson’s request for a declaration of war. When the announcement was made to the American public, the Florida Times-Union echoed the nationalist sentiments sweeping the country, imploring “every American worthy of the name [to] bend his energies to ending the war through victory.” Just two days later, the Florida Naval Militia deployed from training bases in Sarasota, Key West and Jacksonville and reported for duty in Charleston, South Carolina. Soon after, an additional 2,000 Florida National Guardsmen mobilized for service. But aiding the Allied war effort in Europe would require more than reserve forces.

Florida Joins the Fight

In May 1917, Congress passed the Selective Service Act, requiring all men between the ages of 21 and 31 to register for the draft. The law set Florida's initial draftee quota at 6,325 enlistees. Beginning in July 1917, the first round of recruits went out of state to train at either Camp Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina, or Camp Wheeler near Macon, Georgia. An additional 36,000 more men and women would come from all over Florida to join the military during the war. In total, 35,829 joined the Army, 5,963 joined the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard and 238 joined the Marine Corps.

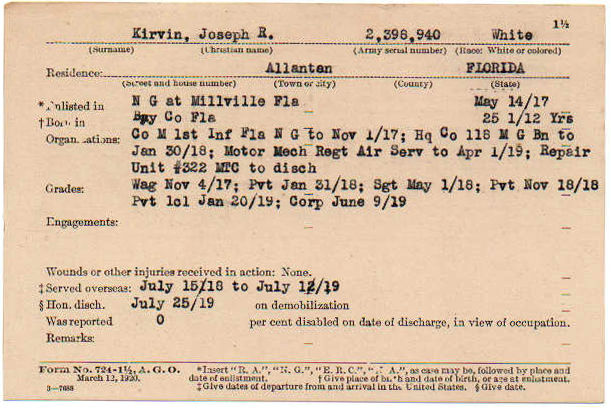

Service card for Pvt. Joseph R. Kirvin from Allenton, FL. Search all WWI service cards.

African-American soldiers made up 36 percent of the total number of Army enlistees from Florida, but they were subjected to the armed services’ strict racial segregation policies. Neither the Navy nor the Marine Corps accepted African-Americans at all. The Army accepted a total of 13,024 African-American enlistees and 7 officers from Florida. With some exceptions, racial barriers prevented African-Americans from enjoying the same career advancement opportunities available to white soldiers. In keeping with Jim Crow custom, African-Americans were more likely to be drafted and assigned to labor battalions, performing menial tasks like cooking and cleaning, and less likely to see combat or receive special recognition for their service.

Several thousand Florida women also joined the military during the war. About 200 women enlisted as Yeoman Class (secretaries) in the Navy and others as nurses in both the Army and Navy.

Profiles of WWI Service from the Archives

Living within the State Archives of Florida are photographs and documents that highlight the diverse military service of Floridians:

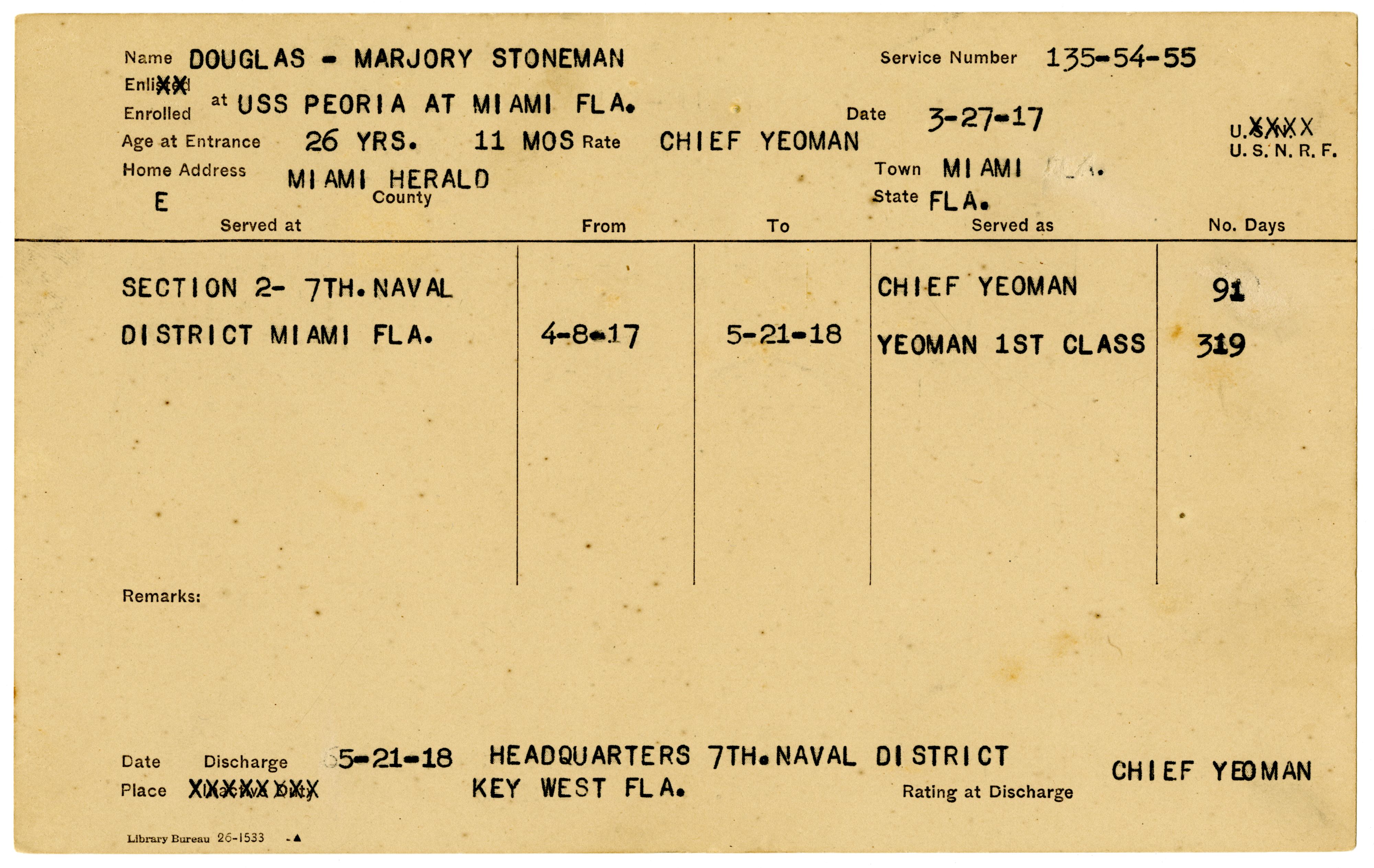

Famed Florida author and environmentalist Marjory Stoneman Douglas served in the Navy and the Red Cross. At the start of the war, Douglas worked for the Miami Herald. She went down to the enlistment office on an assignment to report about the first woman in the city to enlist. But the woman never appeared. Douglas volunteered and instead took the distinction. Initially, she served as a Navy Yeoman First Class administering boat licenses. Douglas then joined the Red Cross, where she traveled to Europe and wrote publicity for the organization.

Private William George McMullen served in the 9th Infantry Regiment of the Second Division, Army Expeditionary Force in France. Originally from Largo, Florida, McMullen enlisted in the U.S. Army in the fall of 1917 at the age of 19. On his decision to volunteer, he later wrote in his memoir that “the government publicity trying to generate a state of patriotism has worked,” leaving him “imbued with [the patriotic] fever covering the nation.” McMullen trained at Camp Screven in Savannah, Georgia, before crossing the Atlantic to fight on the Western Front in France. (For more information see State Archives of Florida, M90-24).

Jacksonville resident Private Mitchell Evans served in the U.S. Army in the 151st Depot Brigade. Evans’ wartime experience was not uncommon for African-American soldiers during the war. He did not deploy to France until near the end of the war and reportedly never saw front-line combat. While civil rights leaders such as W.E.B. DuBois and James Weldon Johnson encouraged black men to enlist, the military’s treatment of black soldiers ignited demands for racial equality after the war. “We are [foolish] if now that the war is over we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land,” DuBois contended. (See all related records on Florida Memory).

Ruth Bryan Owen, who would become Florida's first congresswoman, also joined the Allied fight. She was living in Germany with her husband, Major General Owen when war broke out. She served in England as secretary-treasurer of the American Woman's War Relief Fund. Owen later worked in Cairo, Egypt, as a Voluntary Aid Detachment war nurse during Britain's Egypt-Palestine campaign. Shortly after the war, the couple moved to Coconut Grove, where she launched her political career.

Brothers Algy and Arthur Bevins from Davenport, Florida, served aboard the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Tampa. Algy worked on the cutter as a water tender and Arthur as a fireman. They both enlisted in the U.S. Coast Guard, convinced that the guard service posed the least risk of any military branch. “There are chances against us, but of not nearly so much consequence as trench warfare,” Algy wrote to his parents. Sadly, on September 26, 1918, the Tampa disappeared from its convoy into a patch of fog in the Bristol Channel. A German submarine presumably torpedoed it, killing all 131 people aboard, including 35 Floridians. According to the U.S. Coast Guard, this incident marked the largest single loss of life by any Naval unit during the war. (For more information see State Archives of Florida, N2001-2).

Three of the state’s future governors, Spessard Holland, David Sholtz and Millard Caldwell, took up active duty during the war. Sitting Governor Sidney Catts’ son, 2nd Lieutenant Sidney Catts Jr., served with the 28th Infantry Regiment in France. Former Governor George Franklin Drew’s grandsons, Herbert J. Drew and George F. Drew, also deployed to France.

Many Floridians were honored for their distinguished service during the Great War. France awarded 63 Floridians with the Croix de Guerre and 2 received the Congressional Medal of Honor (Lieutenant Commander William Merrill Corry, Jr. and Chief Machinist’s Mate Francis Edward Ormsbee, Jr.), America's highest military award.

Military Training and Intelligence Facilities

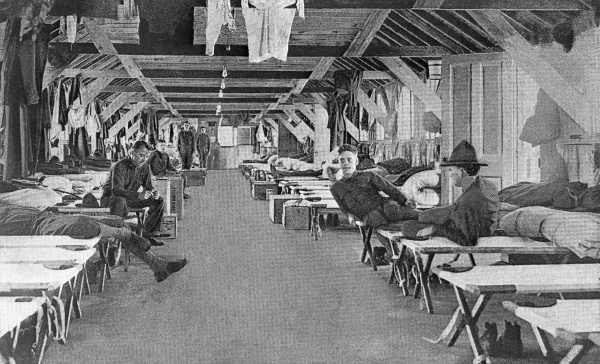

The Sunshine State's subtropical coastlines and wide-open inlands became the site of numerous military training and intelligence facilities during WWI. The largest installment was U.S. Army Camp Joseph E. Johnston in Jacksonville. Originally known as Black Point, the National Guard first used the site beginning in 1909. When the war came, the U.S. Army renamed the site Camp Joseph E. Johnston and opened it as an Army Quartermaster training camp in November 1917. The camp grew to include over 600 buildings and at one time held a population of just under 27,000. Additionally, five of the nation's 35 flying schools operated in Florida: Naval Air Station Pensacola, Curtiss Field and Chapman Field in Miami, and Carlstrom Field and Dorr Field in Arcadia. Inventors Charles Kettering and Lawrence Sperry used the open spaces in Arcadia, or "Aviation City," as it became known during the war, to test guided missiles. Their project did not succeed. Key West's balmy winters also made it an ideal site for Thomas A. Edison, who chaired the Naval Consulting Board during the war, to conduct experiments for the development of depth bombs. President Wilson designated Key West, Tampa and Pensacola as defensive sea areas. Men stationed in those locations utilized an array of flying machines and sea vessels to defend the coasts against enemy attack. Thankfully, no such assault occurred.

Armistice

After Germany’s final defeat on November 11, 1918, Florida’s troops in Europe began returning home. Six months later, in June 1919, President Wilson signed the Treaty of Versailles, which outlined the terms for post-WWI peace. For some, the heavy physical and emotional burdens of modern warfare lingered. Troops were shell-shocked by their experiences in the trenches and their exposure to chemical warfare long after their return home. Nonetheless, the war brought Floridians — many of whom would not have otherwise ventured far from their hometowns — into contact with people from other states and created perhaps the first shared national experience of the 20th century. In his first post-war address to the Florida Legislature in 1919, Governor Sidney Catts reflected on the importance of the state’s contributions to the war and described the war as an effective catalyst for “cementing our own people, as a nation, in the bonds of friendship, unity and strength.”

Listen: The Folk Program

Listen: The Folk Program