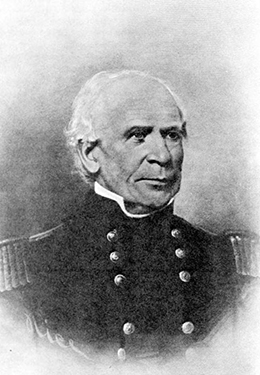

Thomas Sidney Jesup Diary

Brief Biography of Thomas Sidney Jesup

Thomas Sidney Jesup was born on December 16, 1788, in Berkeley County, Virginia. Living on the frontier, Jesup established a work ethic, sense of protection, and paternalism that he carried throughout his military career. In 1808, Congress doubled the size of the federal Army. Jesup enlisted at the age of 19, and was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant without any prior experience.[1] Almost immediately, Jesup criticized the material conditions and operations of the military. He was eager to make changes and experience combat.

During the War of 1812, the Secretary of War appointed Jesup as the Deputy Quartermaster General in charge of providing transportation for General William Henry Harrison’s army on Lake Erie.[2] Promoted to the rank of Major, Jesup commanded the 25th Regiment at Fort Erie and participated in the Battle of Chippewa and the Niagara Campaign. Jesup was wounded four times at the Battle of Lundy’s Lane, but recovered and was promoted to the rank of Brevet Colonel.

After serving as a recruitment officer in Connecticut, Jesup was assigned to command the 1st Infantry of the Southern Division of the Army in 1816. Under the command of General Andrew Jackson, the Southern Division oversaw settlement in Louisiana and protected the boundary with Spanish Florida from Indian raids by Creeks and Seminoles. During his command, Jesup traveled from Baton Rouge to New Orleans to recruit soldiers for his unit.

In 1818, the newly appointed Secretary of War, John C. Calhoun, promoted Jesup to the rank of Brigadier General and Quartermaster General of the Unites States Army. Jesup’s prior experience and study of military service allowed him to make significant changes to the structure, operations and regulations of the Quartermaster’s Department. Under his tenure, Jesup appointed his own subordinates, organized the transportation of troops via steamboat, and kept the army supplied through a careful system of record keeping, business transactions and budget appropriations.

When President Andrew Jackson ordered the removal of the southeastern tribes to the Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River, many Muscogees in Florida, Alabama and Georgia resisted. By the winter of 1835, resistance to removal erupted in Florida and across the Creek Country. What became known as the Second Seminole War began in 1835, and the Second Creek War broke out in 1836.

When the United States Army initially sought to pacify the frontier in late 1835, Jesup remained in the office of Quartermaster General. However, in May 1836, President Jackson ordered Jesup to leave his position and join U.S. regular troops and militia from Georgia and Alabama operating in Florida.[3] Under General Winfield Scott, Jesup was second-in-command and led the Alabamians to join Scott’s Georgians at Fort Mitchell before proceeding to Florida. Communications between Scott and Jesup broke down, which resulted in a scandal within the War Department, further fueled by politicians and journalists. President Jackson recalled General Scott and placed General Jesup in command of military operations in Florida.

A court of inquiry determined General Scott’s campaign had failed. Scott and his supporters blamed Jesup for acting independently and disobeying orders. Nonetheless, Jesup remained in command of the Army in Florida. He was responsible for securing friendly Creek Indians in Alabama and Georgia, and raising among them a militia of 500 warriors to aid in the suppression of hostile Indians in Florida.

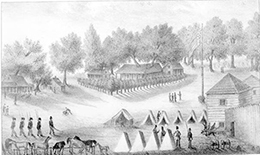

In the fall of 1836, the new Secretary of War, Benjamin F. Butler, ordered Jesup to lead an offensive campaign into the interior of Florida and attack Indians who resisted removal. Jesup commanded the regular army, militia, artillery, mounted horsemen and navy to build a series of forts along rivers and swamps from Tampa Bay to Volusia in an attempt to surround the Seminoles. Using his experience as Quartermaster, Jesup set up an intricate network of depots with supplies, rations and ordinances to sustain the troops. Despite being well-supplied and fortified, General Jessup’s Army struggled to locate the Seminoles.

In January 1837, General Jesup’s reconnaissance reported Seminole strongholds on the headwaters of the Ocklawaha River.[4] At Cypress Swamp, Jesup’s men engaged a force of Indian and black warriors and captured women and children. The warriors fled deeper into the swamp, but because Jesup held their families as prisoners, he sent terms of surrender to the hostile Indian leaders.

Several Seminole leaders, namely Jumper, Alligator, and Abraham, agreed to end hostilities and meet for negotiations on February 18 at Fort Dade.[5] However, these leaders could not speak for all Florida Indians and several bands held out, refusing to negotiate with Jesup. In addition, many leaders failed to return on February 18, and those who came argued against removal. General Jesup then decided to move negotiations to March 4. Four leaders signed a peace pact and agreed to assemble their people for emigration.

General Jesup’s duty as commander was to contain hostages gathered near Fort Brooke (Tampa). Under the terms of the peace agreement, any Florida Indian who resisted removal or ventured north of the Hillsborough River was deemed hostile. In May, Micanopy and other leaders succumbed to Jesup and began assembling their people in detention camps near Tampa. On June 2, 1837, Osceola and Sam Jones (also known as Abieka) kidnapped Micanopy, Jumper, Cloud, and other pro-emigration leaders and liberated the Seminoles awaiting deportation.[6] General Jesup realized that the Seminoles would not submit without a fight and raised additional troops for another offensive campaign.

General Jesup approached the fall of 1837 with a hardline policy towards the Seminoles. In order to prevent delays, Jesup ordered that any Seminole who came to him under a white flag of truce would be detained, lest they escape and continue to fight. He later received harsh and sustained criticism for this policy. Jesup considered any Indian who came into his camp to be surrendering. After Osceola approached the General under a white flag of truce in October 1837, Jesup declared that he and his followers be taken into custody at Fort Marion in St. Augustine.[7]

Jesup is most remembered for capturing Osceola under a white flag of truce. The famed warrior later died at Fort Moultrie in Charleston Harbor. Despite capturing several leaders, many Seminoles and Mikasukis, including Sam Jones and his band, remained scattered across the Florida peninsula. General Jesup employed the help of Micanopy to bring in Sam Jones and his followers. However, Coacoochee, who was captured with Osceola, escaped from Fort Marion and joined Sam Jones at Battle of Okeechobee in December 1837.[8]

After the Battle of Okeechobee, Jesup moved his Army south to meet up with General Zachary Taylor’s force and engaged the Seminoles at the Loxahatchee River. Again, the Indians scattered and after tending to his wounded men, Jesup proceeded south towards the Big Cypress Swamp. Jesup met with several leaders and obliged them to assemble at Fort Jupiter in 10 days.

In the meantime, inspired by their courage, Jesup wrote a letter to President Martin Van Buren asking him to end the conflict and let the Seminoles reside in the uninhabitable areas of South Florida.[9] However, President Van Buren refused Jesup’s plea and stated that he would not waiver from Jackson’s desire to remove all Indians west of the Mississippi River. Jesup once again assembled his Army to pursue the largest resistance groups under Sam Jones and Alligator. But in April 1838, General Jessup was recalled to his Quartermaster post in Washington and his command was turned over to future president Zachary Taylor.

After returning to his duties in Washington, Jesup learned that the promises he made to the Seminoles were being ignored. Jesup supported Seminole appeals and pushed for provisions of land promised to the Seminoles by the Treaty of Payne’s Landing in 1832 and the Treaty of Fort Gibson in 1833 to be upheld. In addition to his political activism on behalf of the Seminoles, Jesup released official records relating to his command in Florida and toured army posts throughout the interior.

When the Mexican War broke out in 1845, the Army depended upon Jesup to transport troops, equipment and supplies to the southwest.[10] At first, Jesup delegated responsibilities to his subordinates while he remained in Washington. By October 1846, Jesup went to Mexico to command operations on the front lines. With the acquisition of new territories as a result of the military victory over Mexico, Jesup pushed for the continued presence of troops and garrisons along the borderland regions. In addition to military support, as Quartermaster General, Jesup advocated for the development of railroads and towns during the last years of his career. While sectional tensions increased during the 1850s, Jesup remained a loyal Unionist. He died on June 10, 1860, at the age of 72.

Download PDF versionNotes

- ^ Chester L. Kieffer, Maligned General: The Biography of Thomas Sidney Jesup (San Rafael, California: Presidio Press, 1979), 4.

- ^ Kieffer, 16.

- ^ Kieffer, 126.

- ^ Kieffer, 158.

- ^ John K. Mahon, History of the Second Seminole War, 1835-1842, rev. ed. (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1985), 199

- ^ Mahon, 204.

- ^ Thomas S. Jesup, Joseph M. Hernandez, K. B. Gibbs and John Ross, “The White Flag,” The Florida Historical Quarterly, 33, n. 3/4, Osceola Double Number (January - April, 1955): 218.

- ^ Frank White, ed., “The Journals of Lieutenant John Pickell, 1836-1837,” The Florida Historical Quarterly, 38, n. 2 (Oct., 1959): 142.

- ^ Mahon, 207.

- ^ Kieffer, 259.

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program