Description of previous item

Description of next item

Native Floridians through European Eyes

Published November 11, 2013 by Florida Memory

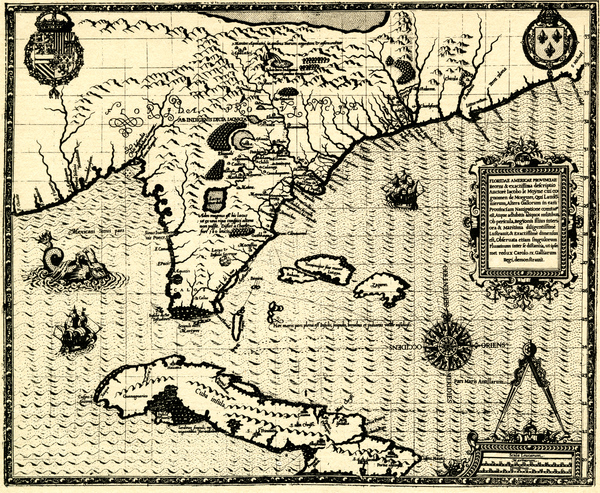

It should be no surprise that some of the earliest images of Native peoples in what is now the United States originated in Florida. The first recorded European expedition to North America, under the command of Juan Ponce de León, landed somewhere along the east coast of Florida in 1513. Several conquistadors followed over the ensuing half century and left a trail of bloodshed across the peninsula.

“Floridae Americae Provinciae Recens & Exactissima,” attributed to Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues and published by Theodor de Bry (1591)

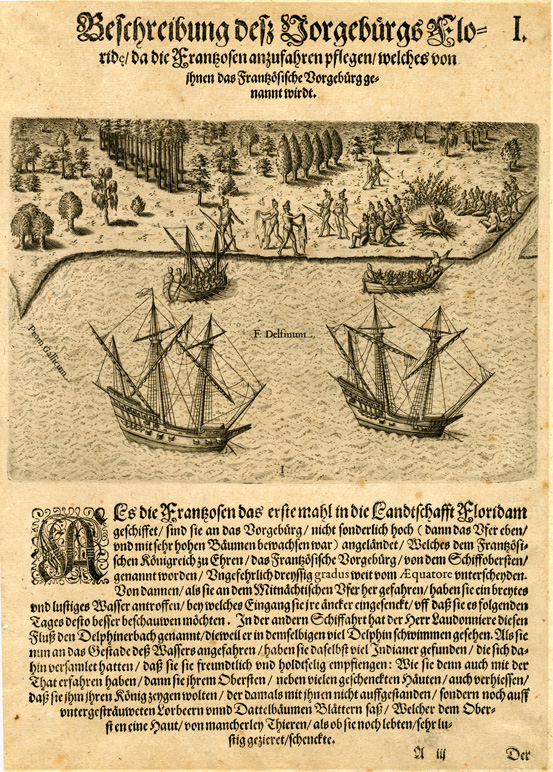

In 1564, the second of two French expeditions landed in northeast Florida near the St. Johns River. They established a short-lived settlement, dubbed Fort Caroline, which survived until it was destroyed by the Spanish in 1565.

Plate I: The Promontory of Florida, at Which the French Touched; Named by Them the French Promontory, by Theodor de Bry (ca. 1591)

One of the members of the ill-fated French settlement, cartographer and artist Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, is credited with creating the earliest known images of Native Floridians during his brief stay. Le Moyne survived the Spanish attack and sought refuge in England upon his return to Europe.

It is unknown whether Le Moyne’s sketches made in Florida survived the journey across the Atlantic, or if he later reproduced drawings from memory. Regardless, by 1591, engraver Theodor de Bry had acquired sketches and an account from Le Moyne’s widow and published them, along with other scenes of the Americas, in a series known as Grand Voyages.

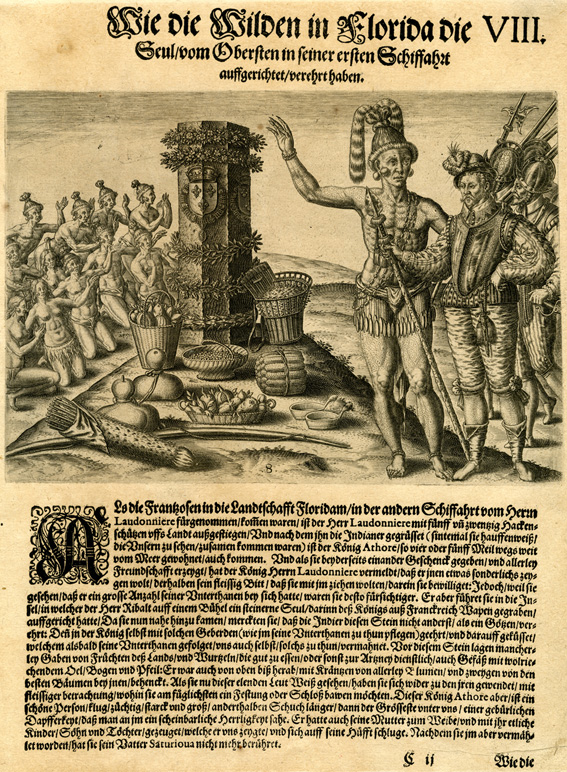

Plate VIII: The Natives of Florida Worship the Column Erected by the Commander on his First Voyage, by Theodor de Bry (ca. 1591)

De Bry’s renditions of Le Moyne’s images are some of the most significant and controversial artifacts that document European activities in 16th century America. Scholars have long pointed out the inaccuracies present in many of the de Bry engravings. Despite the problematic nature of the engravings as a whole, they do provide small glimpses into Native American culture in 16th century Florida.

The images below are among those in the de Bry series that provide hints into the life and customs of Native Floridians. The indigenous people depicted in the images were known as the Timucua, and they inhabited northeast and north-central Florida at the time of first contact with Europeans and Africans in the early 16th century.

The Timucua were divided into several small chiefdoms and subsisted on farming, hunting, and harvesting marine resources. Ethnographic evidence from the 17th century, in the form of documents created by Spanish priests, lend additional credibility to some of the elements portrayed by de Bry in his 1591 publication.

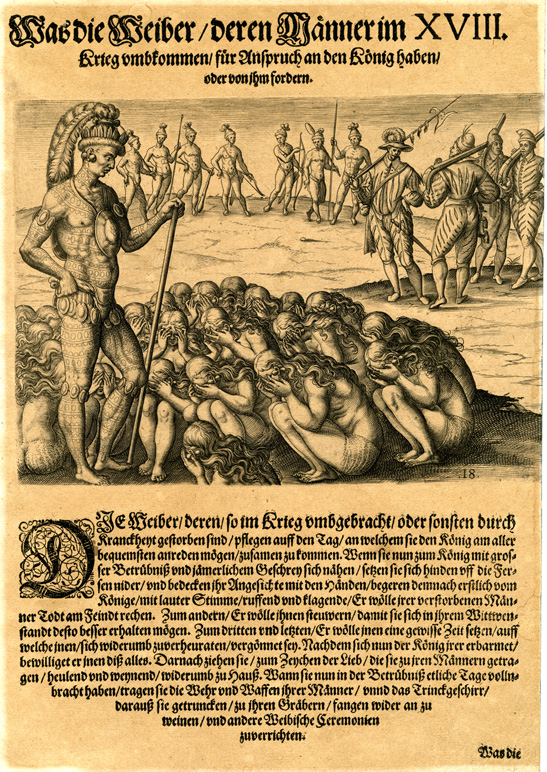

Plate XVIII: The Chief Applied to by Women Whose Husbands Have Died in the War or by Disease, by Theodor de Bry (ca. 1591)

The motivations of the artist are quite apparent in the above image. The European soldiers in the background stand armed with superior technology–guns–while the Native warriors carry only bow and arrows. The intended message was that Europeans need not worry about the military prowess of the Indians, because the Europeans enjoyed far greater firepower.

The portrayal of women kneeling before the chief is more complex. The chief is adorned with elaborate tattoos, a detail unlikely fabricated by de Bry. Later evidence gathered by European observers confirms that Native American men and women tattooed their bodies with a variety of symbols.

The caption that accompanied this image explains that, as part of his chiefly duties, the chief had the power to compel warriors to attack rival tribes and take captives. The captives would then become part of the capturing tribe through ritual adoption.

This image alone might convey to European males the notion that women were subordinate to the chief, and men in general, in their society. However, as elsewhere in the Native southeast, the chief in this case is obligated to the women to launch a military campaign to replace loved ones lost to war or disease.

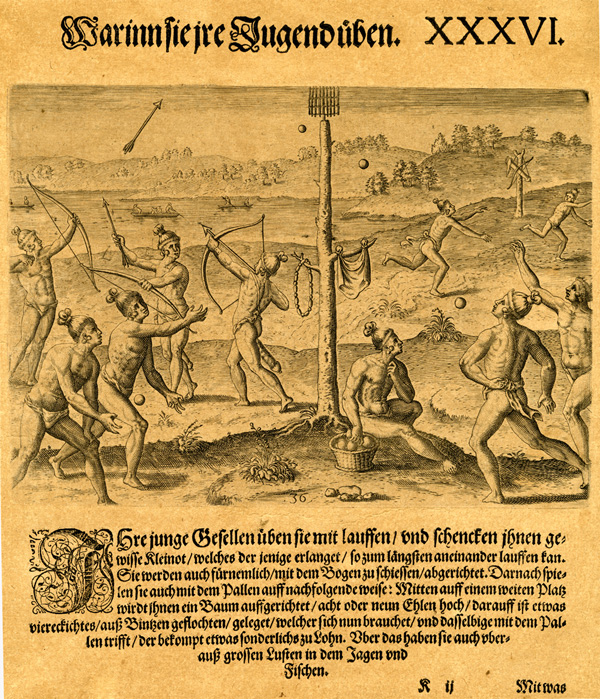

The image above portrays the various types of athletic activity engaged in by Timucuan youth. The pole at the center represents a local version of a game found throughout eastern North America. Sometimes called the ball game, or stickball, tribes from New England to Florida to the Mississippi Valley played versions of this game, and their descendents still do today.

One of the best accounts of the game was collected in 1676 by Juan de Paiva among the Apalachee, western neighbors to the Timucua.

Plate XXII: Industry of the Floridians in Depositing Their Crops in the Public Granary, by Theodor de Bry (ca. 1591)

There are two aspects of the above image worth noting. First, the portrayal of the dugout canoe corresponds to the findings of archeologists throughout the state of Florida. Canoes found in Florida, constructed in the manner depicted here, date from 5,000 years ago to the early 20th century, the most recent versions built by Seminole and Miccosukee Indians.

The second important aspect of this image is the reference to the public granary in the accompanying caption. Evidence from throughout the southeast indicates that certain tribes used public granaries to store and dispense commonly harvested agricultural goods.

In the largest chiefdoms, the chief alone distributed the contents of the granary to his people. Well into the historic period, leaders in the Muskogee world, including the Creeks and Seminoles, maintained public granaries and other methods of communal distribution.

This final image depicts Timucuan methods of cooking meat in the fashion known today as barbecue. The modern English language term barbecue likely derives from baribicu, meaning “scared fire” in Timucuan and related languages spoken by Native inhabitants of the Greater Antilles.

Although we certainly learn more about the ideology and intentions of the European creators of these images than we do about the Native people they portray, the significance of the de Bry engravings cannot be discounted in the history of Native American-European encounters. These images certainly influenced many who saw them and have figured prominently in the European imagination of Native Americans from the time of their creation to the present.

Visit the de Bry engravings collection page on Florida Memory to learn more about the significance and controversy surrounding these remarkable images.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Native Floridians through European Eyes." Floridiana, 2013. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295134.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Native Floridians through European Eyes." Floridiana, 2013, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295134. Accessed March 9, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2013, November 11). Native Floridians through European Eyes. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295134

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program