Description of previous item

Description of next item

Florida and the Civil War (November 1863)

Published November 11, 2013 by Florida Memory

Mission Impossible

The Battle of Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863, was one of the most spectacular and daunting Union victories of the Civil War.

Running north to south for approximately six miles, Missionary Ridge dominates the skyline to the east of Chattanooga, Tennessee. The ridge was the key to the defense of Chattanooga, a city that served as one of the principal railroad hubs of the war. Since September 1863, the Confederate Army of Tennessee, under the command of General Braxton Bragg, held the ridge as part of its line of operations to the south and east of Chattanooga, a line that included Lookout Mountain, the area’s most prominent point. Bragg hoped his positions would allow him to starve out the Union Army of the Cumberland, which had retreated to Chattanooga following its defeat at Chickamauga on September 20. The Union counteroffensive to relieve the siege of Chattanooga culminated in a battle for control of Missionary Ridge, a battle in which Florida regiments played an important role.

Following a reorganization of the Union command in Tennessee, General Ulysses S. Grant took over Federal operations at Chattanooga. Grant replaced the Army of the Cumberland’s Major General William S. Rosecrans, the losing commander at Chickamauga, with Major General George H. Thomas, whose determined leadership in that earlier battle earned him the nickname “The Rock of Chickamauga.” Under Grant’s command, the Union forces at Missionary Ridge consisted of Thomas’s army, two detached corps from the Army of the Potomac under Major General Joseph Hooker, and the Army of the Tennessee under Grant’s favorite general, William Tecumseh Sherman. The combined Union forces totaled more than 56,000 men.

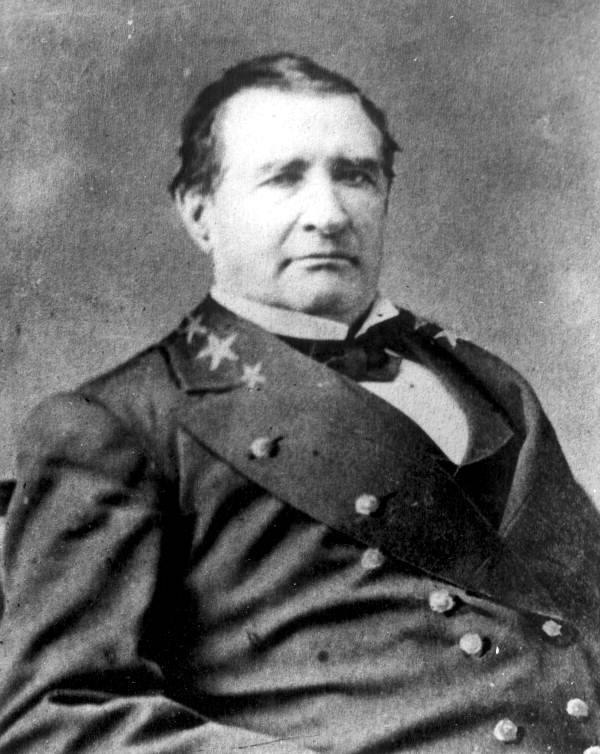

Bragg’s Army of Tennessee totaled some 44,000 men at Missionary Ridge. Organized on the ridge from left to right, the Confederate forces consisted of two corps under the command of Major General John C. Breckenridge and Lieutenant General William G. Hardee. Each corps consisted of four divisions; however, one of Hardee’s divisions had been dispatched to Knoxville, Tennessee, and was not present on the day of the battle. Two of Breckenridge’s divisions made up the left and a portion of the center of the Confederate line on Missionary Ridge, while his two other divisions fought the battle on the extreme right of the Confederate line under Hardee’s corps. Floridian James Patton Anderson commanded one of Hardee’s divisions at the center of the ridge.

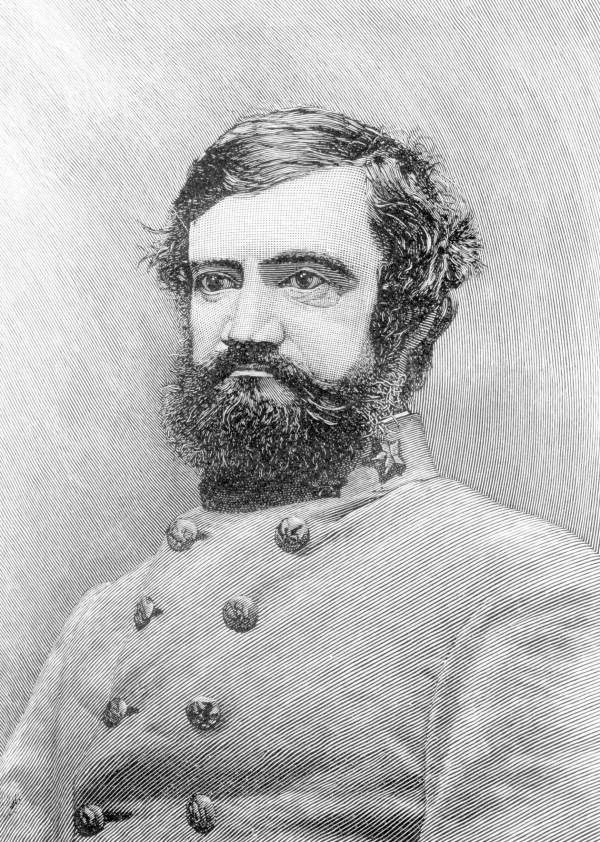

On the left of Anderson, Brigadier General William P. Bate commanded one of Breckenridge’s divisions. Bate’s division included the regiments of the Florida Brigade under the command of Brigadier General Jesse Johnson Finley, former commander of the 6th Florida Infantry Regiment. Finley’s brave leadership of the 6th at Chickamauga earned him Florida Governor John Milton’s highest recommendation for command of the Florida Brigade and promotion to general: “I know of no gentleman whose patriotism, integrity, courage and intelligence, commend him more favorably to my consideration . . . .” The Florida Brigade at Missionary Ridge consisted of the 6th, 1st, 3rd, 7th, and 4th infantry regiments, as well as the 1st Florida Cavalry, Dismounted. Half of the Florida regiments formed a line of rifle pits at the bottom of the ridge, and the other half held positions at the ridge’s crest. Finley’s men just happened to be positioned at the center of the Confederate line, which bore the brunt of the Union assault.

After securing control of Lookout Mountain on November 24, Grant’s corps began their attacks on Missionary Ridge the next morning. The Union attack that broke the Confederate line was not supposed to happen. Grant ordered Hooker and Sherman to attack the southern and northern flanks of the ridge, respectively. When their attacks failed, General Thomas, whose Army of the Cumberland was only supposed to make a faint attack on the Confederate center, launched an all-out assault on his own initiative. His troops quickly overran the Confederate entrenchments at the bottom of the ridge and then charged six hundred feet to the crest to secure the center of the ridge and victory for the Union.

Thomas’s attack ripped into Finley’s Floridians. Due to the Union attacks on the flanks of the ridge, General Bragg ordered some Confederate units from the center to reinforce the flanks, forcing Finley to thin out his lines to cover more ground. As Thomas’s men advanced towards the foot of the ridge, one Florida soldier recollected, “[O]h, what a purity [sic] sight it was to see them charge in 3 solide [sic] columns across the old field as blue as indigo mud and their arms glittered like new.” The three Florida regiments dug in along the bottom of the ridge held their fire until the Federals were almost on top of them. The Floridians fired their volleys but had to retreat in the face of overwhelming numbers.

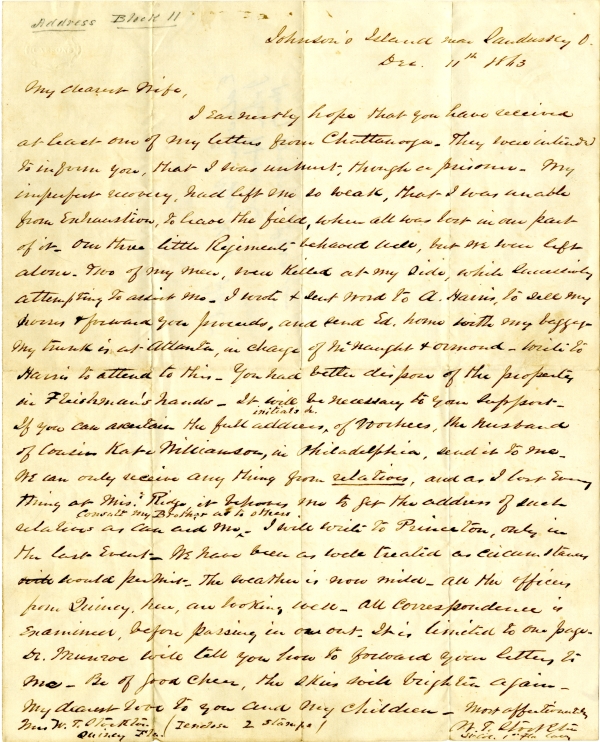

Some of the wounded and most exhausted men could not leave their positions and were taken prisoner, including Lieutenant Colonel William T. Stockton of the 1st Florida Cavalry, Dismounted, who while in Union captivity wrote his wife an account of the fighting and his capture: “Our three little regiments behaved well, but we were left alone- Two of my men, were killed at my side, while successively attempting to assist me.” As they withdrew up the ridge, the Floridians climbed under a rain of Federal bullets into the Confederate line on the crest.

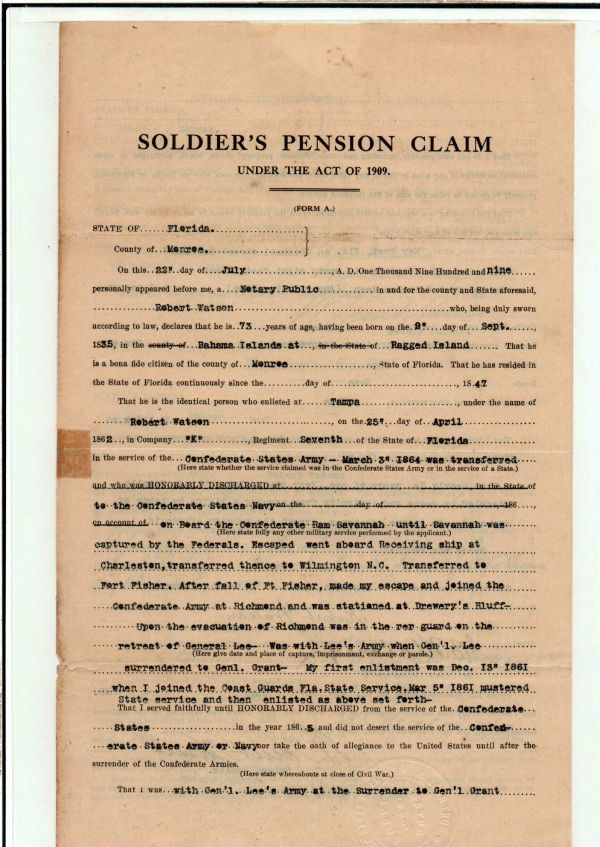

Instead of positioning his men on the ridge along the “military crest,” a position just below the top of the crest, Bragg had mistakenly placed his units on the summit of the ridge, from which it was difficult to see and fire upon the enemy. When the retreating Florida regiments joined their compatriot regiments at the crest, they realized they could not provide effective fire against the oncoming Federals. The six Florida regiments did their best to defend the summit, but had to retreat down the opposite side of the ridge as the Federals overwhelmed their positions. Robert Watson, a soldier in the 7th Florida, related how the Floridians “retreated down the hill under a shower of lead leaving many a noble son of the South dead and wounded on the ground and many more shared the same fate on the retreat.”

At battle’s end on the evening of November 25, Bate’s division began a withdrawal from Tennessee along with the rest of Bragg’s army to Dalton, Georgia, where Bate reported the Battle of Missionary Ridge had cost his unit 857 casualties. Only 33 of the 200 Floridians who had begun the battle at the bottom of the ridge survived to fight another day. The best estimate of the Florida Brigade’s overall casualties places the unit’s losses at 471 men, over half of Bate’s division’s total casualties.

The Floridians had put up a brave fight, but they and the Army of Tennessee could not prevent one of the most impressive Union victories of the war. The Battle of Missionary Ridge left the Union in control of Chattanooga and made possible Sherman’s offensive into Georgia in the spring of 1864. During that campaign, the Florida Brigade of the West would continue its service as the Army of Tennessee fought the Federals all along their advance towards Atlanta.

With the exception of the Milton and Stockton quotes, all quotes come from Jonathan C. Sheppard, By the Noble Daring of Her Sons: The Florida Brigade in the Army of Tennessee (University Press of Alabama, 2012). Sheppard’s book is available at the State Library and Archives of Florida, as are the papers of Governor John Milton and William T. Stockton.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Florida and the Civil War (November 1863)." Floridiana, 2013. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295139.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Florida and the Civil War (November 1863)." Floridiana, 2013, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295139. Accessed March 9, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2013, November 11). Florida and the Civil War (November 1863). Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295139

Listen: The Blues Program

Listen: The Blues Program