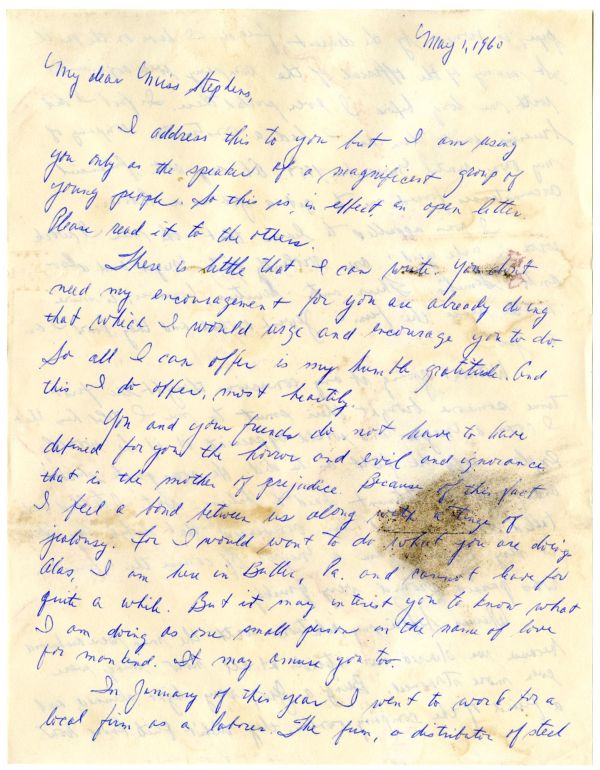

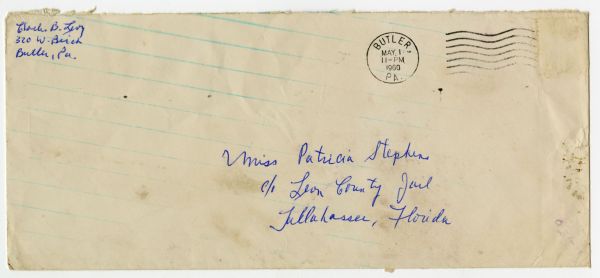

May 1, 1960

My dear Miss Stephens,

I address this to you but I am using you only as the speaker of a magnificent group of young people. So this is in effect an open letter. Please read it to the others.

There is little that I can write. You don't need my encouragement for you are already doing that which I would urge and encourage you to do. So all I can offer is my humble gratitude. God this I do offer, most heartily.

You and your friends do not have to have defined for you the horror and evil and ignorance that is the mother of prejudice. Because of this fact I feel a bond between us along with a tinge of jealousy. For I would want to do what you are doing alas, I am living in Butler, Pa. and cannot leave [?] for quite a while. But it may interest you to know what I am doing as one small person in the name of love for mankind. It may amuse you too.

In January of this year I went to work for a legal firm, as a laborer. The firm, a distributor of steel

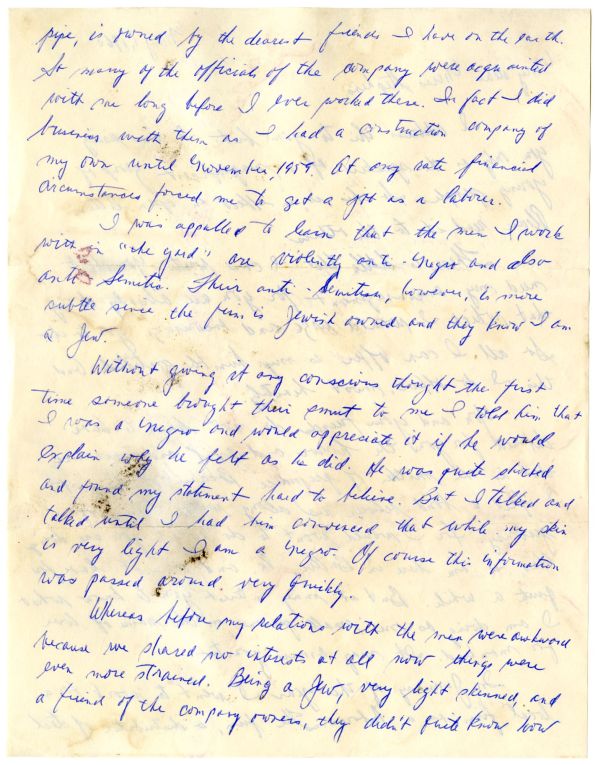

pipe, is owned by the dearest friend I have in the South. So many of the officials of the company were acquainted with one long before I ever worked there. In fact I did business with them as I had a construction company of my own until November [sic], 1959. At any rate financial circumstances forced me to get a job as a laborer.

I was appalled to learn that the men I work with in "the yard" are violently anti-Negro and also anti-Semites. This anti-Semitism, however, is more subtle since the firm is Jewish owned and they know I am a Jew.

Without giving it any conscious thought the first time someone brought their smut to me I told him that I was a Negro and would appreciate it if he would explain why he felt as he did. He was quite shocked and found my statement hard to believe. But I talked and talked until I had him convinced that while my skin is very light I am a Negro. Of course this information was passed around very quickly.

Whereas before my relations with the men were awkward because we played no interests at all now things were even more strained. Being a Jew, very light skinned, and a friend of the company owners, they didn't quite know how

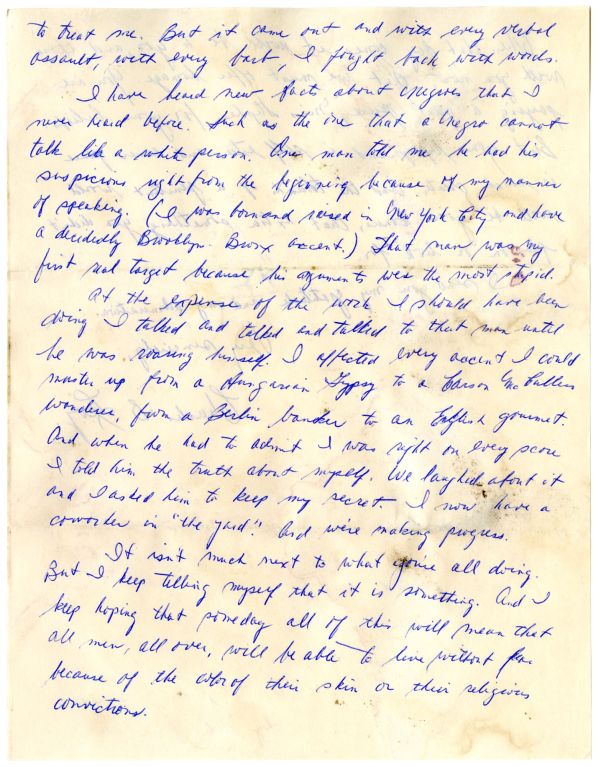

to treat me. But it came out and with [sic] every verbal assault, with every barb, I fought back with words.

I have heard new facts about Negroes that I never heard before. Such as the one that a Negro cannot talk like a white person. One man told me he had his suspicions right from the beginning because of my manner of speaking. (I was born and raised in New York City and have a decidedly Brooklyn-Bronx accent.) That man was my first real target because his arguments were the most stupid.

At the expense of the work I should have been doing I talked and talked and talked to that man until he was [?] himself. I affected every accent I could muster up from a Hungarian Gypsy to a Carson McCullers wonderer, from a Berlin banker to an English gourmet. And when he had to admit I was right on every score I told him the truth about myself. We laughed about it and I asked him to keep my secret. I now have a coworker in "the yard." And we're making progress.

It isn't much next to what you're all doing. But I keep telling myself that it is something. And I keep hoping that someday all of this will mean that men, all over, will be able to live without fear because of the color of their skin or their religious convictions.

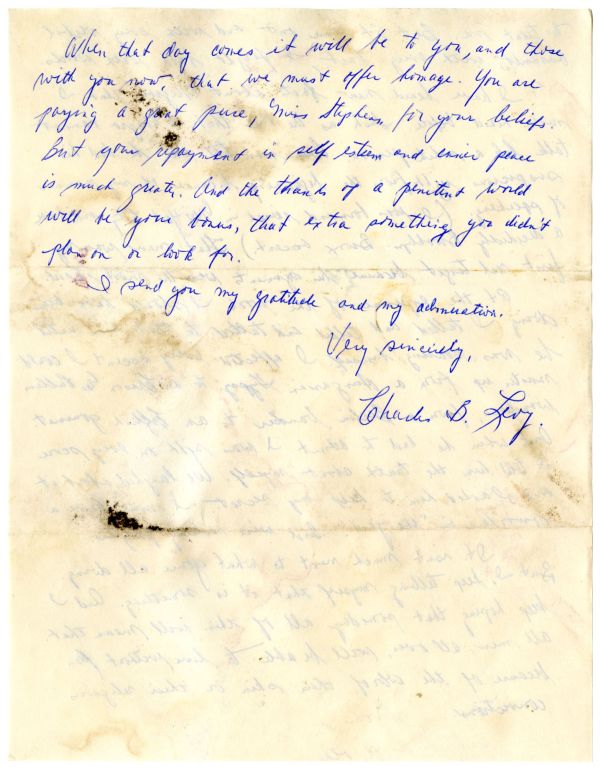

When that day comes it will be to you, and those with you [know], that we must offer homage. You are paying a great price, Miss Stephens, for your beliefs. But your repayment in self-esteem and inner peace is much greater. And the thanks of a penitent world will be your bonus, that extra something you didn't plan on or look for.

I send you my gratitude and my admiration.

Very sincerely,

Charles B. Levy

Listen: The World Program

Listen: The World Program