Description of previous item

Description of next item

The Apalachicola Timber Boom and the Rise of a Black Floridian Working Class

Published March 3, 2023 by Florida Memory

The city of Apalachicola sits at a prime location along the Florida Panhandle. Here the Apalachicola River widens into tidal marshes and merges with the calm blue waters of the Gulf of Mexico. The city known to locals as “Apalach” faced a declining cotton export industry after the Civil War. During Reconstruction, most of the formerly enslaved Black population of Florida worked as sharecroppers. In the 1880s the timber trade transformed the entire Panhandle region into a lumber center for the eastern United States. For many Black laborers, the timber boom provided opportunities for work outside of farming. In the lumber camps and mills, laborers engaged with people from diverse backgrounds. These experiences, paired with higher wages, created new social, political and economic spaces for the rising Black working class.

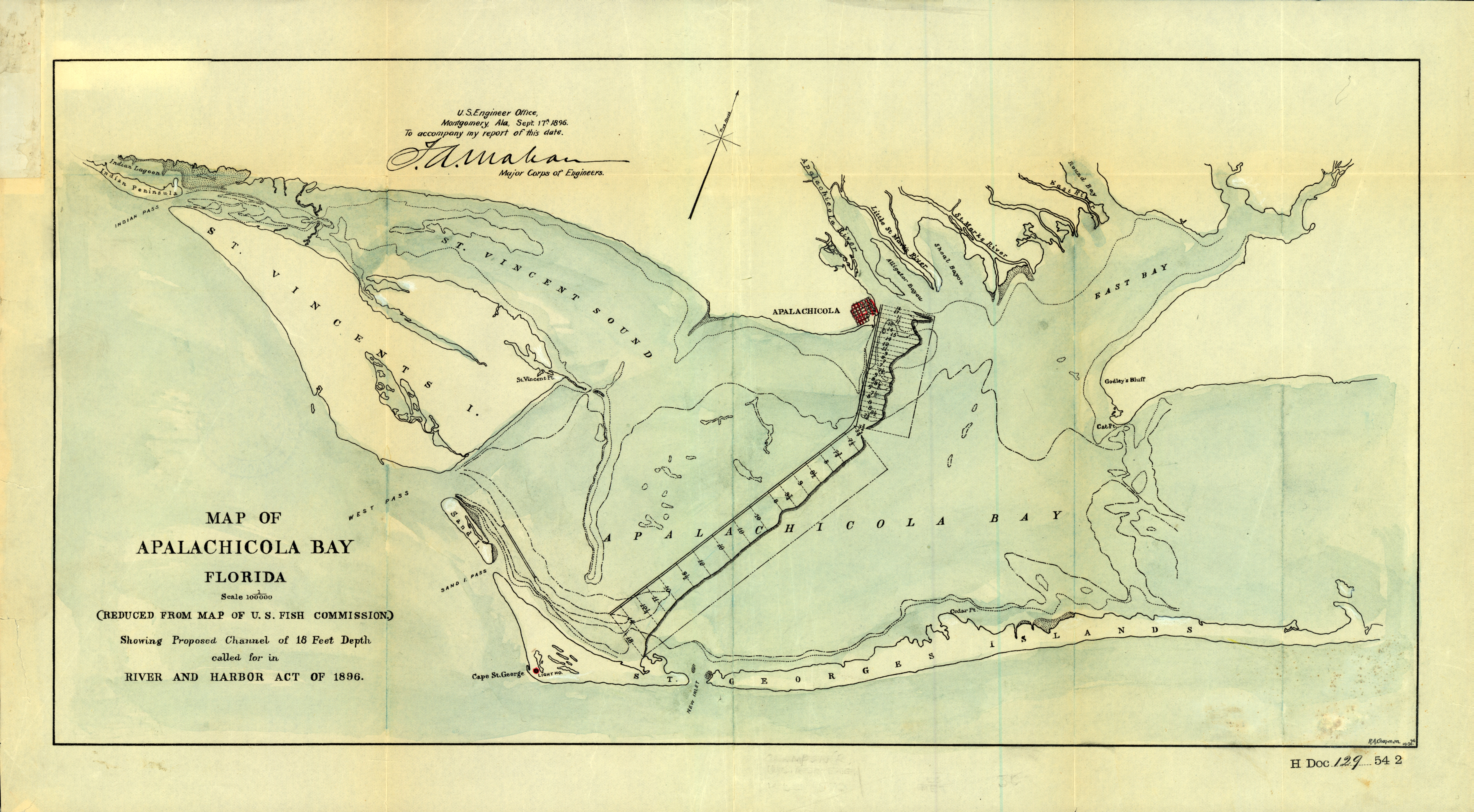

Map of Apalachicola Bay Florida Showing Proposed Channel of 18 Feet Depth Called for in River and Harbor Act of 1896.

Map of Apalachicola Bay Florida Showing Proposed Channel of 18 Feet Depth Called for in River and Harbor Act of 1896.The South lacked industrial infrastructure both before and immediately after the Civil War. In the 1870s, the federal government opened up vast tracts of Florida forest land for purchase. In response, many entrepreneurs bought up huge sections of woodland for logging. The ever-urbanizing North along with Midwestern cities desperately needed lumber. The Great Lakes forests that formerly provided much of the lumber to the Eastern Seaboard had been depleted by the late nineteenth-century. Franklin and other Florida counties in the northern half of the state not only possessed the trees needed for timber but also the workers to process that timber. Workers processed lumber from Florida's forests into a variety of useful products. Shipbuilders had been using sap extracted from pine trees to seal wooden vessels since the 1700s. Workers in these secondary lumber industries processed sap, tar, turpentine and rosin from the lumber harvested in the timber trade.

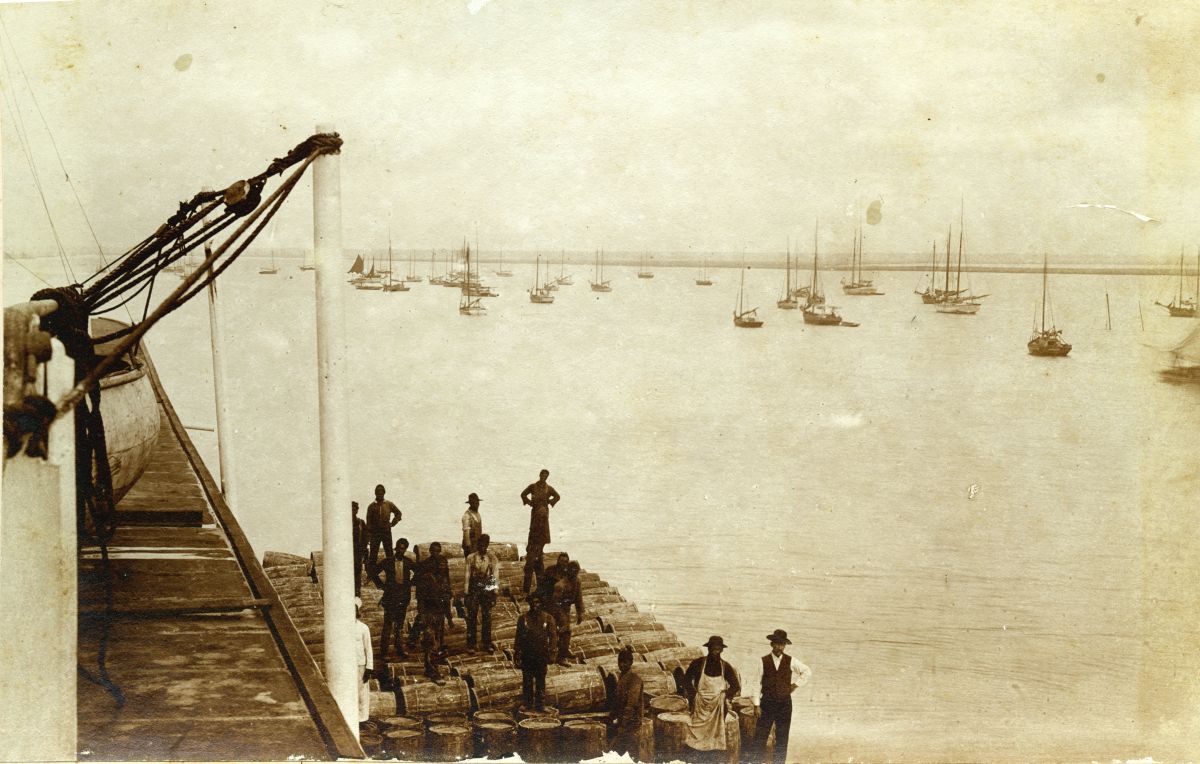

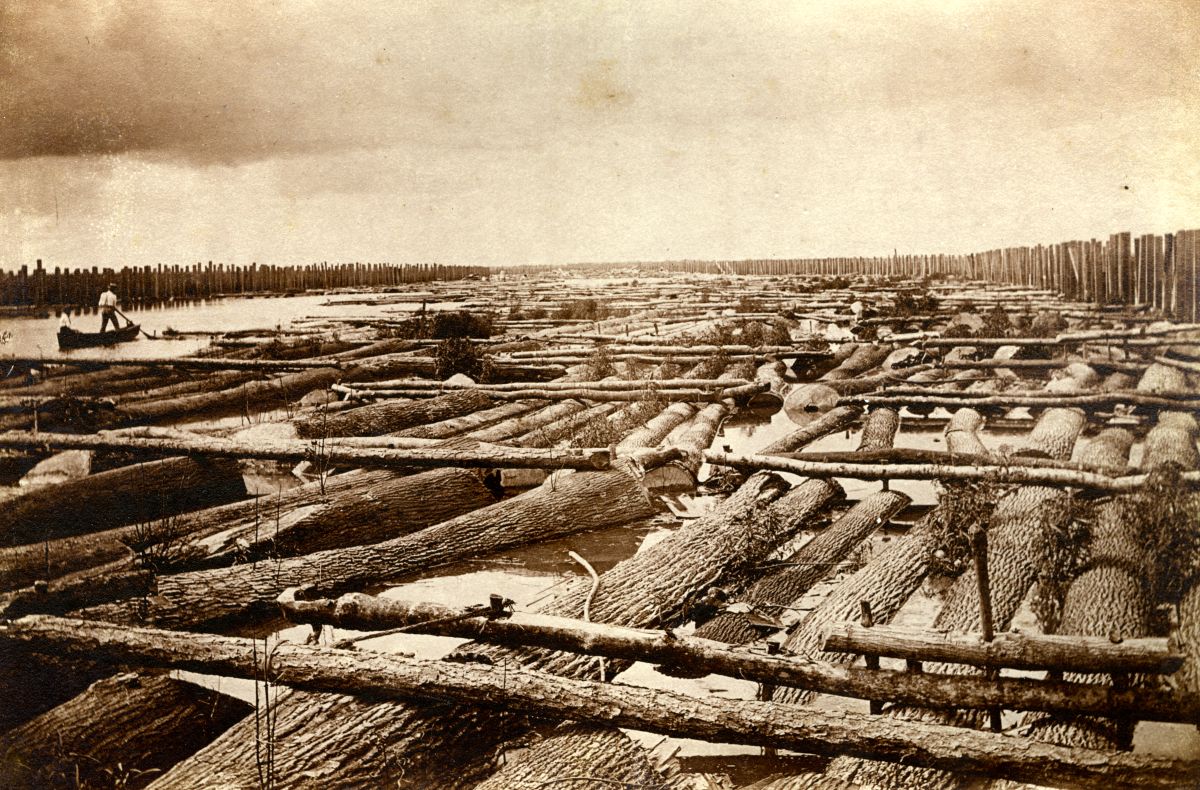

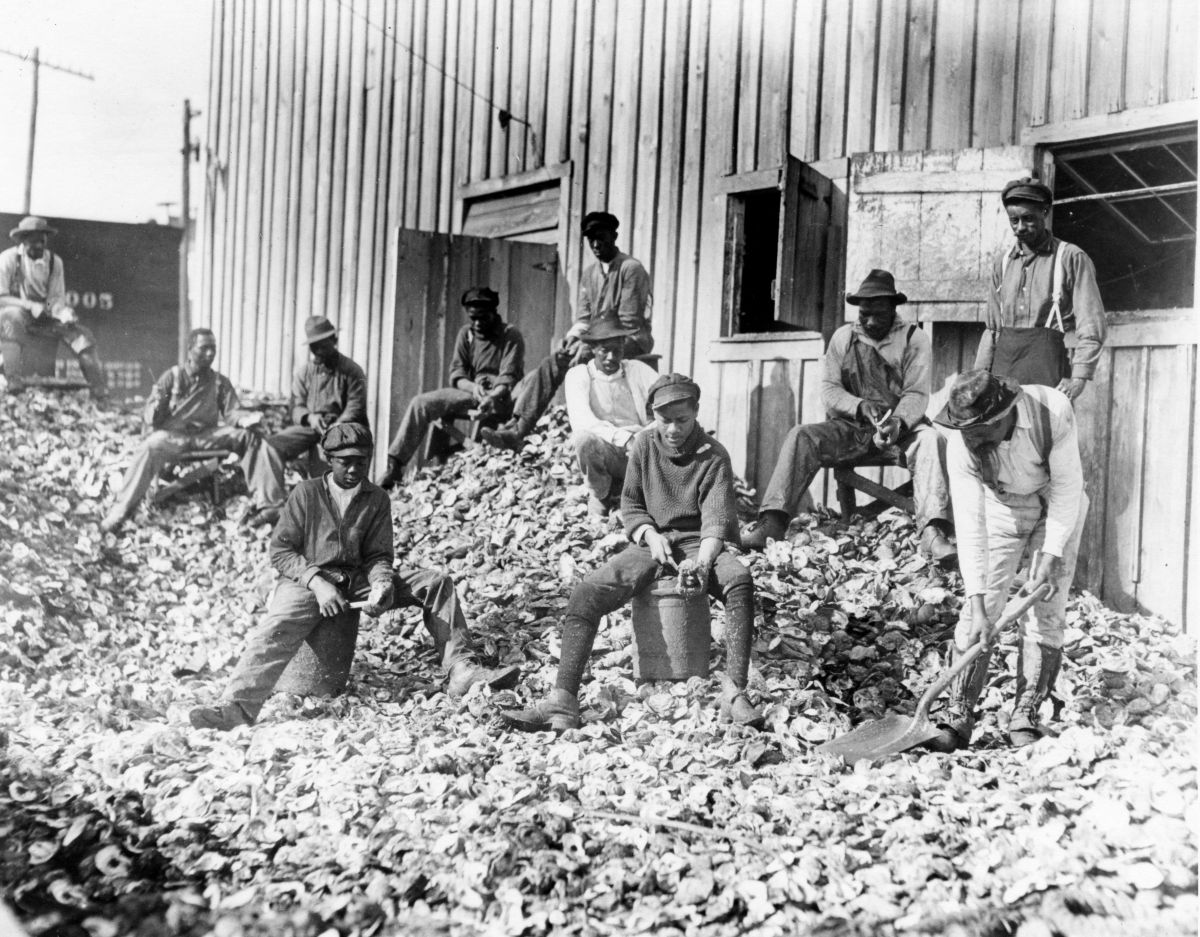

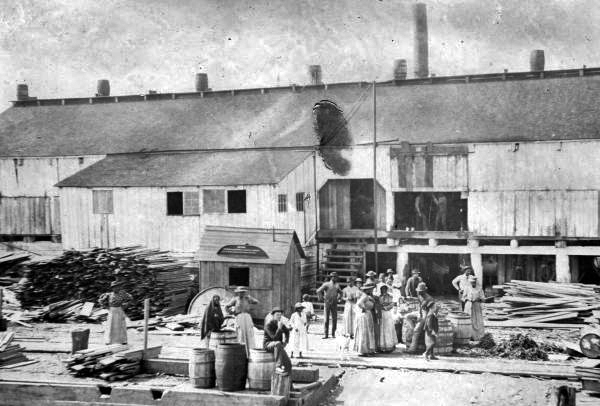

Once the logs had been cut into transportable sections, they would bob down the Apalachicola River into the port town of Apalach. Here workers guided the logs into the various lumber mills built along the water's edge. By the 1880s, companies added logging railroad lines to the mix. The railroad lines allowed for the expansion of logging excursions into areas that lacked adequate waterways. In addition to this new industry in the region, the fishing trade continued to flourish as it had for centuries in the area. Oyster harvesting and canning expanded dramatically in the late 19th century. Here a variety of ethnicities and nationalities mingled within the factories, along the docks and aboard ships destined for ports across the globe.

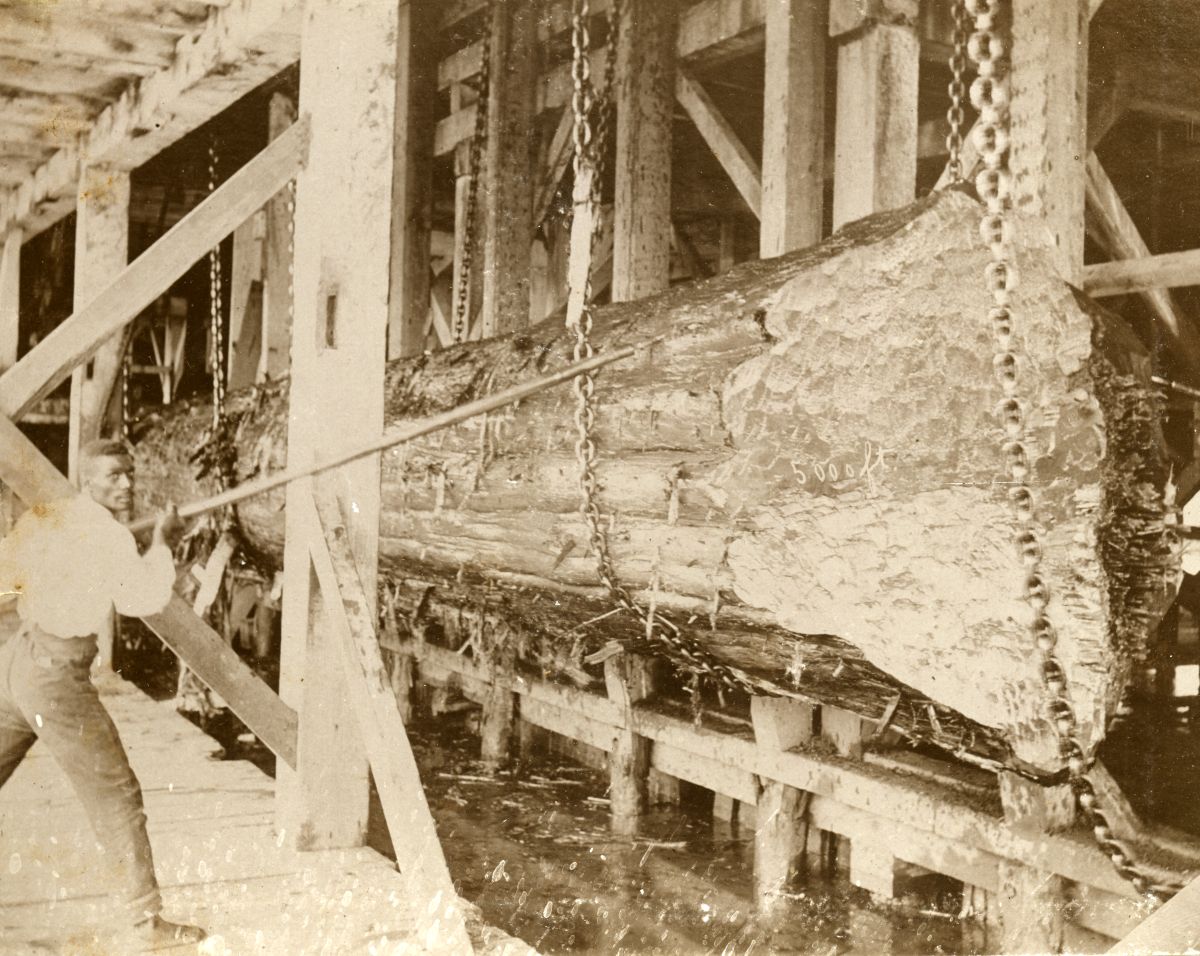

Logging provided steady wages across northern Florida for a variety of laborers. But it was dangerous work. Out in the lumber camps, workers faced grueling conditions. Loggers worked in the stifling Florida heat, often surrounded by alligator and snake-infested swamps. Log dragging machines such as skidders made hauling lumber faster. But these machines also contained metal cables capable of snapping and seriously injuring or killing workers. Once logs arrived at the waterway, ready to float to their next destination, raftsmen risked being crushed should they lose their footing on the slippery wood. Men of the lumber camps also faced the hardships of isolation. Sawmill and factory workers often lived in busy company towns with their families. But the loggers lived farther out in the wilderness with other lumbermen, far from their families back home.

Black men dominated timber work in Northern Florida in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They comprised over half of the total population of loggers in the region. Logging teams were racially mixed, while most other spaces at that time would have been segregated. A logging operation could only be safe and successful if all involved worked as a cohesive team. In this way, the racial differences could not play a role in the day-to-day work of the timbermen. In the evenings, the workers would return to their logging camps. Companies separated workers by race in the living and dining sections of the worker quarters. Despite the segregated organization of the camps, Black and white people spent many of their leisure hours together. These miniature and often temporary communities of male workers dotted the forested landscape outside of cities such as Apalachicola.

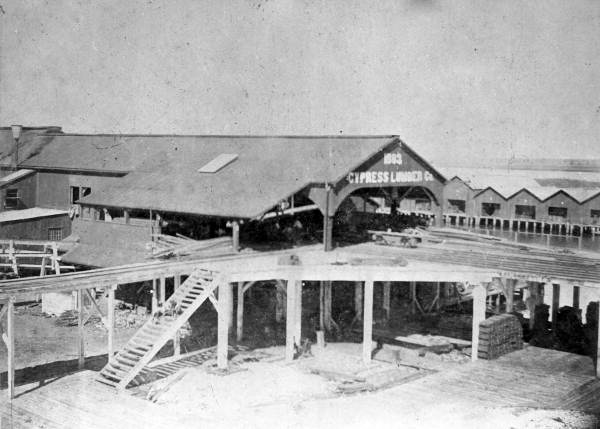

Downriver in the city of Apalachicola, workers processed logs into usable materials. Companies then shipped these materials out across the nation and around the globe. By the late 1800s, improvements in saw technology made processing much faster than in centuries past. Innovations to mills such as steam power sped up production, but also sped up the pace of work, increasing the risk of injuries. With these new technologies, mills ran every day and throughout the year. In the process, the mills created a new and industrially-specialized permanent working population in the surrounding areas. By the 1890s, many laborers were second-generation sawmill workers. These men were married with families, and in North Florida, a little over half of these workers were Black. In the late 1800s, however, Black workers did not usually receive managerial or skilled labor positions. This dynamic changed rapidly in the lumber industry at the turn of the century. Even during the Jim Crow era, one-third of the white workers in the mills of North Florida would be supervised by Black men. A steady increase in both career mobility and wages did not occur because of political or cultural progress related to race. The need for workers in the logging forests and mills grew ever greater and the pull of a less restrictive North for Black people grew stronger. This imbalance forced lumber company owners to offer better opportunities to Black workers if they wanted to retain them.

The timber trade in North Florida offered new opportunities for workers from all backgrounds. But this industry also created new problems for its laborers. Florida barreled ahead of other Southern states in expanding industries. In addition to timber, phosphate and cigar factories flourished. But Florida lagged far behind in protecting workers through injury compensation laws. The court systems of the state usually sided with employers over employees when it came to workplace injuries. With few legal protections, workers frequently organized and advocated for better wages. Florida wages fell short of the national average when compared to the wages of other timbermen in the United States. Employers did not guarantee set work hours for employees. Lumber yards and mills frequently shut down for several days due to machinery failures and sometimes longer in cases of fires. Company owners often purposefully limited production in times of surplus lumber or low demand. This practice resulted in random layoffs for laborers. With so many workers living in company camps and towns, company owners found ways to nickel and dime employees even after they left the mill for the day. Company owners charged workers living in the camps for room and board along with any meals taken there. The owners frequently took these charges out of a worker’s monthly pay. Often, employers paid workers in company-specific currency called “scrip." Workers could only use this business-specific currency in company-owned stores. This restriction severely limited workers who wished to shop outside of company-owned businesses.

The unique history of Apalachicola created a black community with a strong tradition of independent work even in the antebellum period. Apalachicola had not been as entrenched in the plantation patterns of chattel slavery as other Southern port cities such as Savannah had. The city itself had a small enslaved population that frequently worked for families in town. Many enslaved people also worked in the oyster and shrimp industries. This familiarity with local industries outside of the plantation economy encouraged Black people to remain in the region after the Civil War. Eventually, they would become some of the earliest Black free workers in the Apalachicola timber trade.

During the late 19th century, Black residents of Apalachicola created institutional support networks in the form of Black churches, such as St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church. They also developed new local chapters of fraternal organizations such as the Colored Odd Fellows. These mutual aid societies assisted workers when injured on the job. They would even provide compensation to their families in case of accidental death while working. During the Reconstruction era, Black people in Apalach took active part in local government positions. Black men worked in law enforcement and on the local school board. Black citizens in the city created a vibrant community known as “The Hill.” This section of the city featured Black-owned businesses and residences. This Black neighborhood also housed white residents creating an integrated urban area not commonly seen in the Southeastern United States at the time.

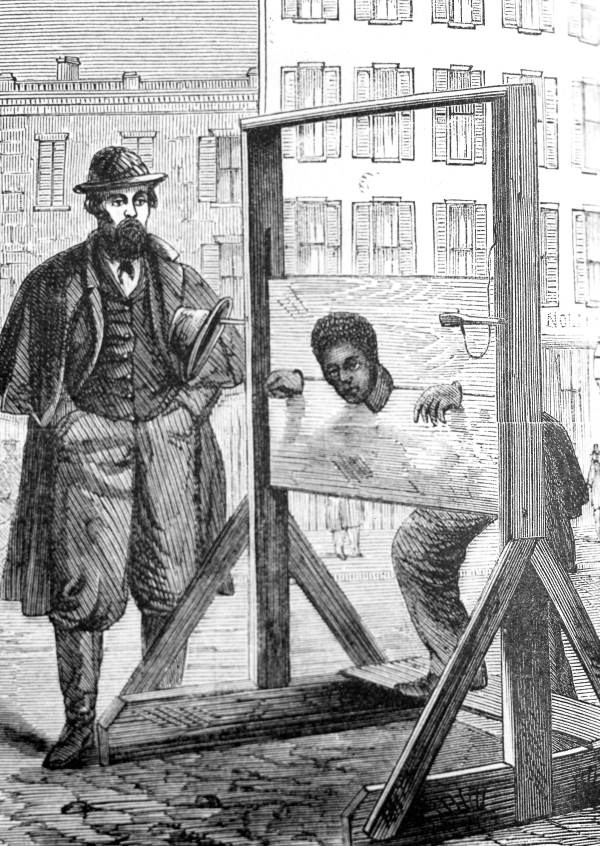

Despite the advantages of living and working in Apalachicola, Black people in the city still faced many hardships there. Prior to the Civil War, city officials in Apalachicola used a variety of methods to control free Black populations in the city. Black sailors could not leave their ship when docked at the port. White patrols maintained a strict curfew for both enslaved and free Black people in the area. After the Civil War ended, Apalachicola’s government enforced numerous legal and social restrictions on Black residents. By the 1890s, decades after slavery had ended, Black citizens still faced cultural and economic restrictions that severely limited their lives. Even with these restrictions, the Black population of Apalachicola grew steadily in the 19th century. At the end of the Civil War, Black people had represented around 28 percent of the total population of Franklin County. By 1890, Franklin County contained just over 3000 people according to that year’s census data with Black people making up 41 percent of that number.

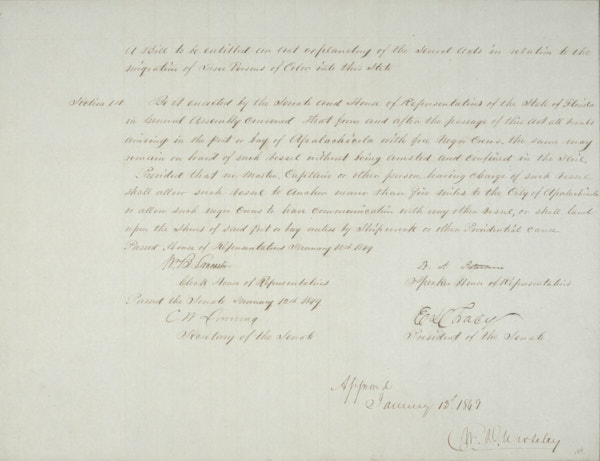

A Bill to Be Entitled an Act Explanatory of the Several Acts in Relation to the Migration of Free Persons of Color into This State, January 13, 1849

A Bill to Be Entitled an Act Explanatory of the Several Acts in Relation to the Migration of Free Persons of Color into This State, January 13, 1849By the end of the 19th century, three major mills existed in Apalachicola. The Kennedy Lumber Company mill, the Kimball Lumber Company mill, and the Cypress Lumber Company mill were all located along the river. There were also multiple smaller mills scattered across Franklin County. Steamboats and clipper ships still brought in fish from deeper waters. Dock workers still hauled goods to and from the wharves. Oystermen and women continued to gather and shuck their wares into piles that dotted the periphery of the port city. In all of these spaces, Black laborers comprised a large percentage of each industry's workers. More than any other industry, the timber trade’s expansion into Apalachicola brought new opportunities for Black resistance and empowerment In some cases, such as the Apalachicola General Strike of 1890, that power would be shown in specific ways. Black workers would protest and strike for better working conditions and wages at the lumber mills. But more broadly, the timber boom of Northern Florida in the late 19th century gave Black laborers a louder voice in Florida society. This voice didn’t just come from their economic value as workers, but also because of the communities they formed in the lumber camps and Black neighborhoods of the Apalachicola River basin.

Further Reading

Lumbermen and Log Sawyers; Life, Labor, and Culture in the North Florida Timber Industry, 1830-1930 by Jeffrey A. Drobney.

African American Sites in Florida, Chapter 18: Franklin County, by Kevin M. McCarthy.

Southern Prohibition; Race, Reform, and Public Life in Middle Florida, 1821-1920, Chapter 6: “Good Order:” Local Option in Franklin County by Lee L. Willis.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "The Apalachicola Timber Boom and the Rise of a Black Floridian Working Class." Floridiana, 2023. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/350838.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "The Apalachicola Timber Boom and the Rise of a Black Floridian Working Class." Floridiana, 2023, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/350838. Accessed February 14, 2026.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2023, March 3). The Apalachicola Timber Boom and the Rise of a Black Floridian Working Class. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/350838

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program