The Florida Seminoles

Photos and History

Seminole Origins

The Creek Indians spoke the Muscogee language and lived in parts of what are now Alabama and Georgia. Their territory extended about as far south as the modern Florida-Georgia border. By the mid-1700s, some Creeks began migrating into Florida. They became known as simanolis, meaning “those that camp at a distance” in the Muscogee language. To the Spanish, they were known as cimarrons, or “runaways.” The two terms merged and became “Seminole” in the English language by the late 1700s.

"A General Map of the Southern British Colonies" (ca. 1776)

Image number: PR06652

Seminole Towns

The settlement called Cuscowilla was the largest Seminole town in the mid-1700s. It was located on the Alachua Savannah, near modern-day Gainesville. The Alachua Seminoles herded thousands of cattle on wet prairies and grasslands. In addition to herding cattle, Seminoles planted fields of corn, beans, and squash.

Many of Florida's current place-names, such as Tallahassee and Okeechobee, come from the Muscogee language.

"An Indian town, residence of a chief" (1835)

Image number: RC07272

Seminole towns with wooden houses, ceremonial ball fields, livestock, and small-scale farming were found near rivers, lakes, and streams in southern Georgia and northern and central Florida in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

Black Seminoles

Slaves escaped from southern plantations joined the Seminoles in Florida. To historians, they became known as “Black Seminoles” or “Seminole Maroons.”

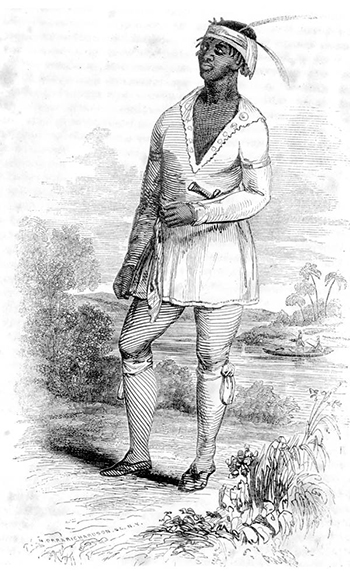

Abraham, interpreter and war leader (ca. 1838)

Image number: RC08709

Abraham escaped slavery in Pensacola and joined the Seminoles. He interpreted and provided counsel for Micanopy during the Second Seminole War.

John Horse, interpreter and war leader (1842)

Image number: RC08718

John Horse was also known as Gopher John. He provided counsel for Osceola during the Second Seminole War and led Black Seminoles into battle.

The First Seminole War

The U.S. Army fought a series of wars against the Seminoles. Conflict increased near the Georgia-Florida border in 1816 and 1817. Secretary of War John C. Calhoun ordered General Andrew Jackson to invade Spanish Florida and pursue the Seminoles. This became known as the First Seminole War.

With Jackson's invasion, Spain recognized that they were losing control of Florida. In 1819, Spain agreed to sell the territory to the United States. The transfer became official in 1821.

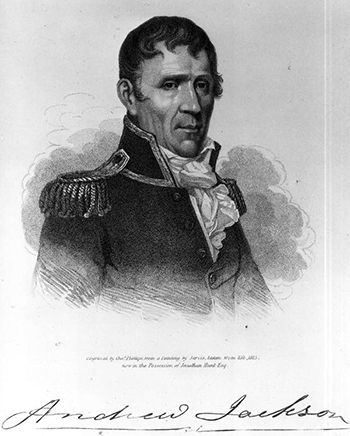

Andrew Jackson (ca. 1815)

Image number: GV000473

Andrew Jackson led an invasion of Spanish Florida in 1818. This conflict became known as the First Seminole War. Some Creek Indians were allied with Jackson and participated in raids on Seminole and Black Seminole settlements.

The Indian Removal Act

The U.S. government felt they needed to separate American and Seminole towns in Florida. In 1823, Seminole and American leaders met at Camp Moultrie. Some Seminoles agreed to move to land in central Florida. Many opposed the terms of the treaty.

In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. It required Native Americans to leave the southeast and migrate west of the Mississippi River. Each tribe negotiated a separate treaty. Most Seminoles strongly opposed removal.

Osceola, a Seminole warrior and leader

Image number: RC0-471

Osceola fought against removal during the Second Seminole War. General Thomas Sidney Jesup pretended that he wanted to negotiate a truce. Instead, he captured Osceola. The American public considered this a violation of the rules of war. Osceola went to prison in St. Augustine. Later he was moved to South Carolina. He died in prison on January 30, 1838.

Note the inaccuracy of the teepees shown in the background. Seminoles in Osceloa’s time lived in log cabins and thatched roof structures later known as “chickees.”

The Second Seminole War

The treaty for Seminole removal was known as the Treaty of Payne’s Landing. The Seminoles did not intend to abide by the agreement forced upon them.

On December 28, 1835, Major Francis Dade led troops north from Fort Brooke along the Fort King road. Suddenly, Seminole warriors ambushed Dade and his men. Within a few hours, all but three of the 110 American troops lay dead. This event was known as the Dade Massacre, or Dade’s Battle. It ignited the Second Seminole War—the longest and costliest Indian war in United States history.

The Seminoles staged a series of raids on plantations in East Florida. Warriors burned plantations and liberated enslaved Africans. This created panic along the Florida frontier. Many settlers fled to nearby forts for protection.

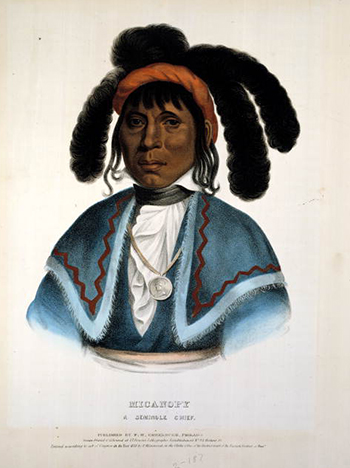

Micanopy, a Seminole chief (1836)

Image number: RC0-470

Micanopy was the principal leader of the Alachua Seminoles in the early stages of the Second Seminole War.

The Second Seminole War lasted seven years and cost the United States an estimated $40 million. In response to the initial success of Seminole war tactics, the U.S. Army changed strategy. They searched out Seminole towns. They burned villages, destroyed crops, and stole livestock. Men, women, and children were captured. The Seminoles were imprisoned at Fort Brooke. Later they were deported to Indian Territory. The United States Army dubiously captured several Seminole leaders under flags of truce, including Osceola, Micanopy, and Coacoochee.

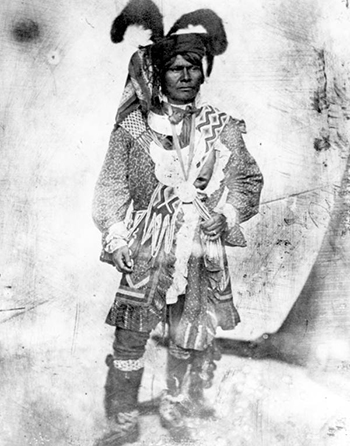

Billy Bowlegs, a Seminole warrior and head-man (1852)

Image number: RC00958

Billy Bowlegs, a head-man of the Alachua Seminoles, led Seminole warriors in the Second and Third Seminole Wars.

The Army declared an end to the war in 1842. Only 500-600 Seminoles remained in Florida. Before the war, the Seminole population was about 5,000.

Tensions persisted and nearly resulted in another war in the late 1840s. A third conflict broke out in 1855. An additional 160 Seminoles left Florida for the Indian Territory. By 1858, the Seminole population in Florida was less than 200.

Listen: The World Program

Listen: The World Program