Distant Storm: Florida's Role in the Civil War

A Sesquicentennial Exhibit

Florida’s Role in the Civil War

Before 1861: Florida’s Journey into Civil War

Sectionalism

Although abolitionists and the tariff were major irritants to Southern planters and slave owners, the spark that ignited the sectional controversy between North and South that would eventually lead to civil war in 1861 was the reopening of the question of the expansion of slavery during the war with Mexico (1846-1848), and the subsequent American acquisition of vast Mexican territories in the West.

A majority of voters and politicians on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line favored a compromise that would extend the Missouri Compromise line of 1820 to the Pacific (the line allowed slavery below latitude 36°30 and outlawed it above), or allow settlers in the territories to vote for or against slavery (popular sovereignty).

However, extreme pro-slavery adherents in the South led by Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina denounced any compromise as a violation of the states’ constitutional right to have slavery. Calhoun called on the southern states to stand united in favor of the expansion of slavery, resistance to compromise and support for the right of secession.

In 1849, Mississippi led the call for a pro-slavery convention of all the slaveholding states to be held in Nashville in June 1850. Florida was one of nine Southern states that sent delegations to Nashville.

By the time the convention opened, however, the South was less enthusiastic about the idea of confrontation and was moving towards compromise: the Compromise of 1850 became law in September.

The majority of the delegates favored moderation as well. They passed a resolution which endorsed the constitutional right to slavery and agreed to a separate resolution calling for the extension of the Missouri Compromise line to the Pacific, but failed to pass language in support of secession. Since Congress was still debating a compromise solution when the convention met, the delegates decided to adjourn and resume their deliberations in November, when they could respond to congressional action.

The Compromise of 1850, which among its elements brought California into the Union as a free state and allowed the possibility of slavery in the Utah and New Mexico territories, quickened the fading enthusiasm of the majority of delegates for a reassembly of the Nashville Convention.

When the convention reconvened on November 11 it contained fewer but more radical delegates, most of whom opposed the Compromise of 1850, supported secession and favored the organization of another larger convention to protect Southern rights.

The preamble to the resolutions makes clear that race and slavery were the core issues of the convention: the delegates proclaimed that differences between whites and blacks “forever forbid their living together on terms of social and political equality,” and argued that the demise of slavery would “end in convulsion, and the entire ruin of one or both races.”

While neither incarnation of the Nashville Convention had much immediate impact, the idea of southern nationalism would linger and enable secessionist views to re-emerge more powerfully and fatefully in a future November, that of 1860.

Charles J. McDonald, a former governor of Georgia, presided over the November 1850 session of the Nashville Convention. As presiding officer, it was McDonald’s duty to forward a copy of the convention’s “Preamble and Resolutions” to every governor of a slaveholding state for presentation to their respective legislatures.

Governor McDonald sent the following copy to Governor Thomas Brown of Florida. A Whig and firm Unionist, Governor Brown opposed secession and, it seems, never presented the document to Florida’s General Assembly.

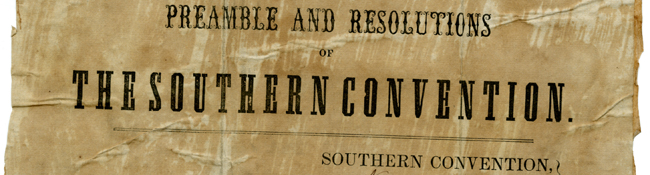

Preamble and Resolutions of the Southern Convention

PREAMBLE AND RESOLUTIONS OF THE SOUTHERN CONVENTION

SOUTHERN CONVENTION

Nov OCTOBER 18TH, 1850

The following Preamble and Resolutions were reported by the Committee on Resolutions, and adopted by the Convention:

We the delegates assembled from a portion of the States of this Confederacy, make this exposition of the causes which have brought us together, and of the rights which the States we represent are entitled to under the compact of union.

We have amongst us two races, marked by such distinctions of color, and physical and moral qualities, as forever forbid their living together on terms of social and political equality.

The black race have been slaves from the earliest settlement of our country, and our relations of master and slave have grown up from that time. A change in those relations must end in convulsion, and the entire ruin of one or both races.

When the constitution was adopted, this relation of master and slave, as it exists, was expressly recognized and guarded in that instrument. It was a great and vital interest involving our very existence as a separate people, then as well as now.

The States of this Confederacy acceded to that compact each one for itself, and ratified it as States.

If the non-slaveholding States, who are parties to that compact, disregard its provisions and endanger our peace and existence by united and deliberate action, we have a right, as States, there being no common arbiter, to secede.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which once again opened the issue of the expansion of slavery into the West, and the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision of 1857, which declared slaves property and called for the enforcement of fugitive slave laws in the North, increased sectional tensions and brought the political struggle over slavery to a new level of crisis.

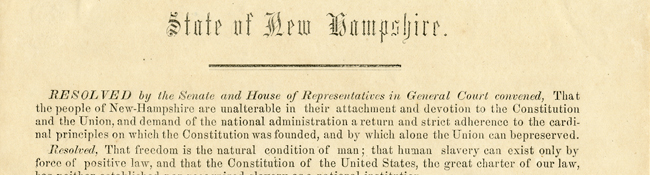

In these resolutions, which Florida’s governor condemned as “offensive and incendiary,” the State of New Hampshire reconfirmed its stand against the expansion of slavery, Dred Scott, and Southern slaveholding interests (other northern states passed similar resolutions).

Note: Compare the New Hampshire resolutions to the “Preamble and Resolutions of the Southern Convention.” A reading of both documents makes it clear that the growing divide over slavery was unlikely to be bridged by moderation from either section.

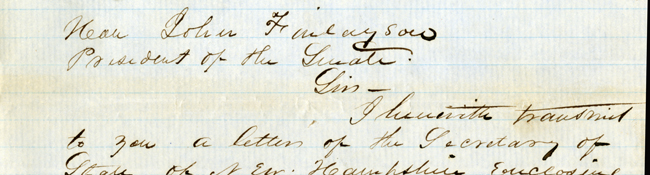

Governor Madison Starke Perry to John Finlayson, forwarding anti-slavery resolutions from the State of New Hampshire to the State of Florida, December 1, 1858

(Series 2153, Territorial and Early Statehood Records, 1821-1878)

Executive Department

Tallahassee Dec 1st 1858

Dear John Finlayson

President of the Senate

Sir

I herewith transmit to you a letter of the Secretary of State of New Hampshire, Enclosing Certain Resolutions adopted by the State which you will please communicate to the House over which you preside.

I have not acknowledged the receipt of those Resolutions, because of their offensive and incendiary character but do not feel authorized to withhold them from the General Assembly.

Very Respectfully

M. S. Perry

Anti-slavery resolutions from the State of New Hampshire to the State of Florida, December 1, 1858

(Series 2153, Territorial and Early Statehood Records, 1821-1878)

State of New Hampshire

____________

RESOLVED by the Senate and House of Representatives in General Court convened, That the people of New Hampshire are unalterable in their attachment and devotion to the Constitution and the Union, and demand of the national administration a return and strict adherence to the cardinal principles on which the Constitution was founded, and by which alone the Union can be preserved.

Resolved, That freedom is the natural condition of man; that human slavery can exist only by force of positive law, and that the Constitution of the United States, the great charter of our law, has neither established nor recognized slavery as a national institution.

Resolved, That the recent attempts of the national government by promises and threats, to coerce the people of a territory desiring to be admitted into the Union, to the introduction and support of human slavery, are unprecedented and atrocious, and merit universal reprobation.

Resolved, That the legislation of the country and the expenditures of its resources, being directed mainly for the benefit of the slaveholding minority of the inhabitants, it is the imperative duty of the immense majority of freemen whose interests are disregarded, and whose rights are violated, to combine in political action to insure their own protection and security.

Resolved, That the action of the state department of the United States in refusing to grant passports to persons of African descent, contrary to previous practice, and of the treasury department in refusing to grant them registers for their own vessels with the right to navigate them as masters, and of the interior department in refusing them the right of entry upon the public domain to become purchasers, is an unjust and illegal denial and invasion of the rights of citizens of New Hampshire.

Resolved, That we are compelled to believe that these invasions of the rights of our citizens are the result of the Dred Scott decision coupled with a desire on the part of the national administration to favor and strengthen the slaveholding interests, which will continue so long as slavery remains a ruling element in the government of the country.

Listen: The World Program

Listen: The World Program