Pestilence, Potions, and Persistence Early Florida Medicine

Midwifery

Julia (Jule) Graves

Julia Graves, One of the First Midwives Certified by the State Board of Health

In several letters sent to the past director of the Florida Midwife Program, Julia Graves described some of the most exciting stories from her early work as a nurse for the state.

In this letter, Graves describes trying to reach the community of La Belle, near Ft. Myers. There were several expectant mothers in the community in need of medical care, so Graves drove a car through a flooded swamp.

After becoming stuck on a submerged stump, Graves was rescued by another passing traveler, whose children's births she had recorded for the state some time before.

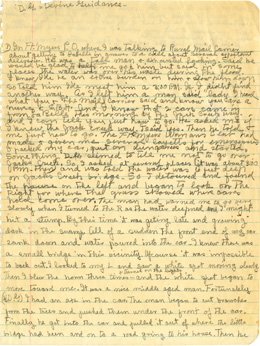

"Divine Guidance," September 4, 1933

In manuscript pages written by Julia Graves, the long-term nurse and midwife for the State Board of Health described some of the most harrowing experiences she had while trying to provide health services to isolated areas of the state or areas suffering emergencies.

She described trying to get from Live Oak to Jacksonville and the Board headquarters in order to begin traveling to West Palm Beach to help people during a hurricane in September 1933.

As a "state nurse," she had to use whatever means necessary to reach those in need, including travelling during dangerous weather conditions and even hitchhiking.

During the hurricane, Graves and other nurses witnessed the work of "death squads" that collected dead bodies, and she described the difference in smell between a dead human and a dead animal. The State Board of Health, through its employees like Julia Graves, faced seemingly insurmountable tasks during environmental and health crises. Graves’ stories reflect both the daunting conditions and situations she and others faced, and the heroism exhibited by so many health workers.

In these pages, Graves also revisits a story about trying to reach the community of La Belle outside of Ft. Myers when the Caloosahatchee River had overflowed. Graves credits "Divine Guidance" for her decision, contrary to local advice, to not attempt to use the "Jack's Creek" route to get to La Belle. She later learned that the route was six feet under water by the time she would have made it there. Divine Guidance also helped her survive after her car was swamped, and she was still able to assist the pregnant women in the La Belle area.

In another recollection, Graves described the questions she asked of rural African-American women about "baby catchers" and "conjurers" who had treated patients in the area. Graves helped compile a list of midwife superstitions and traditions that the certification program would later use in training, and she shows in her stories her ability to access that information in order to communicate with patients and families in rural communities.

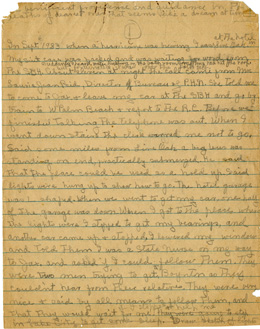

Doll Drawings

Julia Graves, an early participant in the Florida Midwife Program, designed a series of mother and baby training dummies after practicing as a nurse-midwife and instructor for years. She submitted her designs for patent registration.

Graves was able to have working full-size and miniature training dummies produced after having her ideas patented.

Midwife being trained in proper diapering technique (194-)

Image number: SBH0150

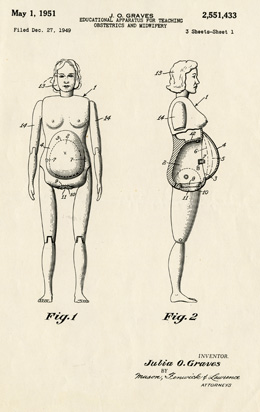

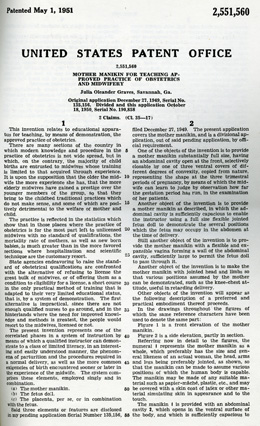

Patent Certificate

Julia Graves received her patent for "Mother Manikins for Teaching Practice of Obstetrics and Midwifery" on May 1, 1951.

Seventy years old at the time, Graves worked on her design for decades before having her designs patented.

Patent Drawing and Descriptions

For the patent application, submitted December 27, 1949, Graves included an additional diagram of her invention and extensive descriptions of all the features and functions of the "Educational Apparatus for Teaching Obstetrics and Midwifery."

In an original application and subsequent revision, Graves described the mechanical innovations present in the doll and its usefulness in demonstrating techniques.

Graves emphasized the importance of training midwives in order to reduce infant and maternal mortality, since it was impractical to eliminate the practice of midwifery altogether.

The invention represented "one of the correlated phases in a system of instruction by means of which a qualified instructor can demonstrate to a class of limited literacy, in an interesting and easily understood manner" normal delivery procedures and types of emergency situations. The system included a mother mannequin, a fetus doll, and a placenta.

Patent Rights for Dolls

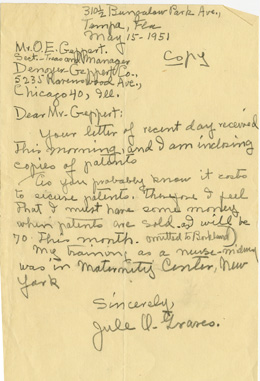

In a letter to Mr. O. E. Geppert of the Denoyer-Geppert company on May 15, 1951, Julia Graves discussed the possible transfer of patent rights to the company, which produces medical and scientific training models.

Miss Julia Graves at the State Board of Health headquarters: Pahokee, Florida (1928)

Image number: N031889

L-R: M. Safan(?), sanitary inspector, Miss Julia Graves, nurse, Dr. H. Mason Smith.

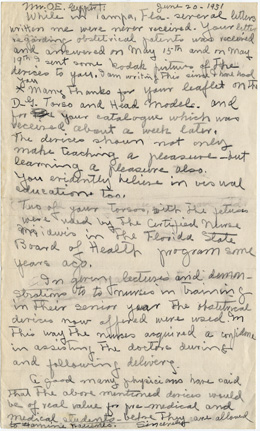

"Of Real Value," Graves Letter of June 20, 1951

The letter from 1951 to Mr. O. E. Geppert for the Denoyer-Geppert company explains how very useful the different training mannequins used by the Midwife Program were, and how some physicians had suggested that they would be helpful for training doctors as well, before the students were introduced to real patients.

"Why the Doll Had Been Made"

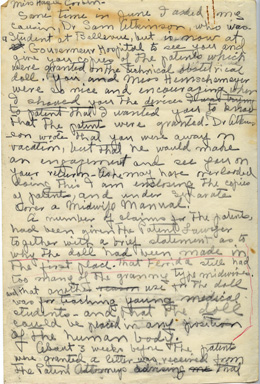

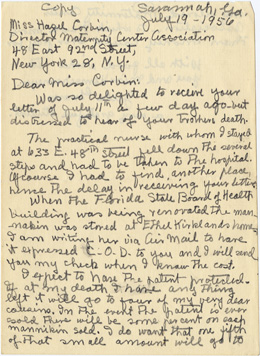

Julia Graves wrote this letter to Hazel Corbin, a midwife instructor, telling Corbin about the patent for the instructional mannequin and the reasons Graves initially designed it.

She described the process of getting the patent drawings and accompanying documents approved and the ongoing need to train new midwives and remove "granny midwives" from practices, and thanked Miss Corbin for the training she had received years before at the Lobenstein Clinic and Maternity Center.

The Fate of “Miss Chase,” the Obstetrical Mannequin

Writing to Hazel Corbin in New York, Julia Graves explained the fate of "Miss Chase," the obstetrical mannequin. The mannequin was being held in a private home after the State Board of Health Building had been renovated.

Graves also expressed her intention to have the patent royalties for her invention be divided among her relatives upon her death.

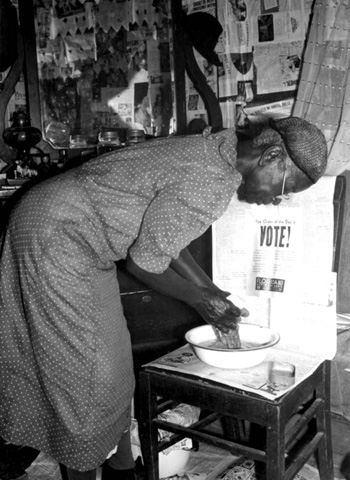

Midwife washing her hands prior to examining patient (1944)

Image number: RC18518

Listen: The Blues Program

Listen: The Blues Program