Florida in World War I

Floridians Who Fought Over Here

While tens of thousands of Floridians committed to military service during the Great War, 900,000 additional civilians made a variety of important contributions on the homefront. The war injected a renewed patriotism into Floridians’ hearts and minds. They bought liberty loans and war savings stamps, produced and conserved food, built ships, raised county militias and volunteered with service organizations like the Red Cross. Schools emphasized military training and American traditions. The 1917 Florida Legislature passed the "Flag Law" mandating that "the flag of the United States be displayed daily" in every state government and public school building. State health officials warned that "not only a future military army, but future industrial army" depended on raising healthy children.

Out of this heightened nationalism came a closer relationship between the operations of the state and federal government, but it also brought about some domestic shifts. Anti-German sentiment swept many pockets of the country, and African-Americans, searching for better job opportunities and racial tolerance, flocked en masse to northern factories. Women suffragists leveraged President Wilson’s appeal for global democracy to expose American democracy’s own shortcomings.

Between 1917 and 1918, the material and intangible sacrifices of Florida’s civilian army aided in securing Allied victory in Europe. After the armistice, the Sunshine State’s economy simultaneously benefited from increased civilian buying power brought on by post-war deflation and Florida’s new image as an untapped source of high-return real estate investments.

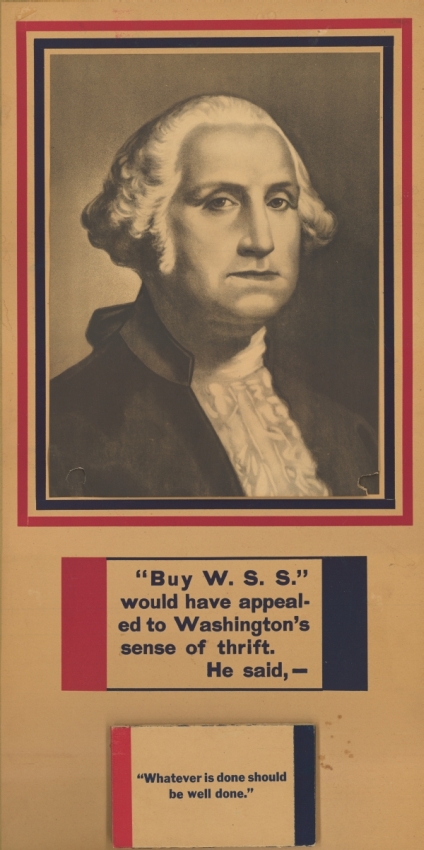

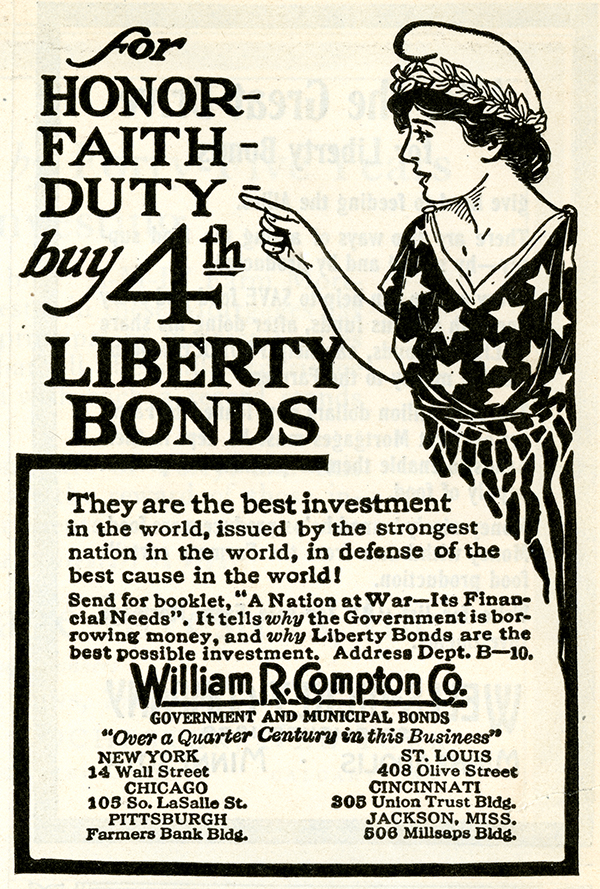

Eager to do their part for the future of global democracy, Floridians readily answered Washington’s national homefront directives — mostly through purchasing liberty loans and increasing food production. When Secretary of the Treasury William G. McAdoo introduced the liberty bond campaign as a way to involve all Americans in the war effort, Floridians, ambitious to show their support, went above and beyond in subscribing to liberty and victory bonds. The State Board of Education bought $50,000 worth of liberty bonds in 1918, but many others invested their money in the more inexpensive war savings stamps to support the Allies. May Mann Jennings, a former first lady of Florida, chaired the Women’s Florida Liberty Loan Committee, through which she oversaw and helped organize local war bond drives.

"Food Will Win the War"

Food became Florida’s most important contribution to the war. When the director of the U.S. Food Administration, Herbert Hoover, decreed that "food will win the war," Floridians responded by ramping up food production in the state. Exactly one month after the U.S. entered the Great War, Governor Catts issued the "National Crisis Day" Proclamation, imploring all Floridians to make "every practical effort ... toward the increasing of food supplies in this state and in the United States." Amid an economy saddled with inflated wartime prices of food, clothing and farm equipment, Floridians volunteered to limit their use of meat, sugar, oil, soap and gas.

Read More: Governor Catts' "National Crisis Day Proclaimation"

Just as the availability of open land in Florida supported the installation of several new military bases and airfields during the war, the state’s large tracts of resource-rich terrain supported the homefront. Officials from the Florida Department of Agriculture encouraged people to fulfill their "patriotic duty" by raising their own livestock and growing beans, corn, onions and wheat for both personal consumption and exportation. Governor Catts appointed Eartha M. M. White, a social worker and businesswoman from Jacksonville, to the Farm and Food Conservation Committee. The committee urged Americans to preserve their crops via canning. Further, the University of Florida’s Agricultural Experiment Station dispatched agents to organize home demonstrations on food preservation in each county. "The real test of your work came when war was declared," said the director of the program, Peter H. Rolfs, to his staff. Scientists also researched pest control and fertilizers in hopes of increasing food production. In order to maximize the efficient transportation of these and other supplies, U.S. Congress passed the Railway Administration Act of 1918, temporarily federalizing all railroads. This allowed for planting of crops along the railroad routes in Florida. For instance, the Seaboard Airline Railway contracted with U.S. Signal Corps to plant 10,000 acres of castor beans, which yielded oil used in the production of essential wartime products.

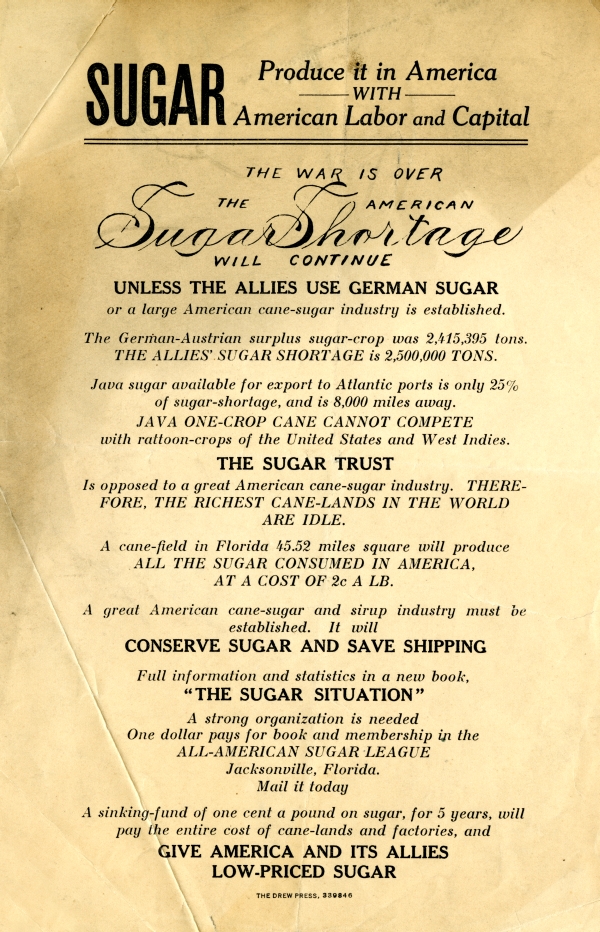

A sugar shortage during the war spurred the onset of large-scale sugar production in the Florida Everglades, though some of the biggest investors would not come until after the war. In 1915, the Southern States Land and Timber Company bought acreage near Lake Okeechobee, where they first experimented with sugarcane production. The company emerged as the primary sugar corporation in Florida during the war. In 1918, C. Lyman Spencer, president of the All-American Sugar League, declared that "Florida must become a sugar-producing state," calling on Florida investors to stop importing sugar from Cuba and Europe and "convert Southern Sunshine into foodstuffs for American and European tables!"

in Florida, ca. 1918.

Manufacturing

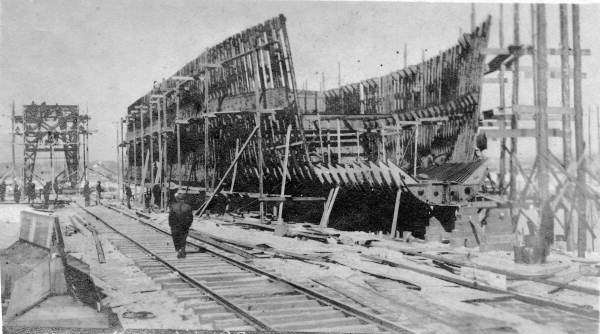

Florida lumber helped build massive defense vessels. At a shipyard in Jacksonville, laborers set to sea 23 steamships and two concrete tankers. Shipyards in Tampa turned out 24 steel ships and four wooden ships. The Millville shipyard in Bay County produced one barge. After the Germans sunk numerous steel ships, the U.S. government called on lumber mill owners to cull north Florida’s abundant pine forests for the manufacturing of wooden ships, but many of those ships eventually fell victim to enemy destruction as well.

Excerpt from an interview with W. H. Hammack, May 19, 1978. In 1916, Hammack operated a lumber mill in White Springs. During WWI he moved to Jacksonville to work in a shipyard. Hammack helped build 82 liberty ships and 9 tankers. (View full record)

Anti-German Sentiment on the Homefront

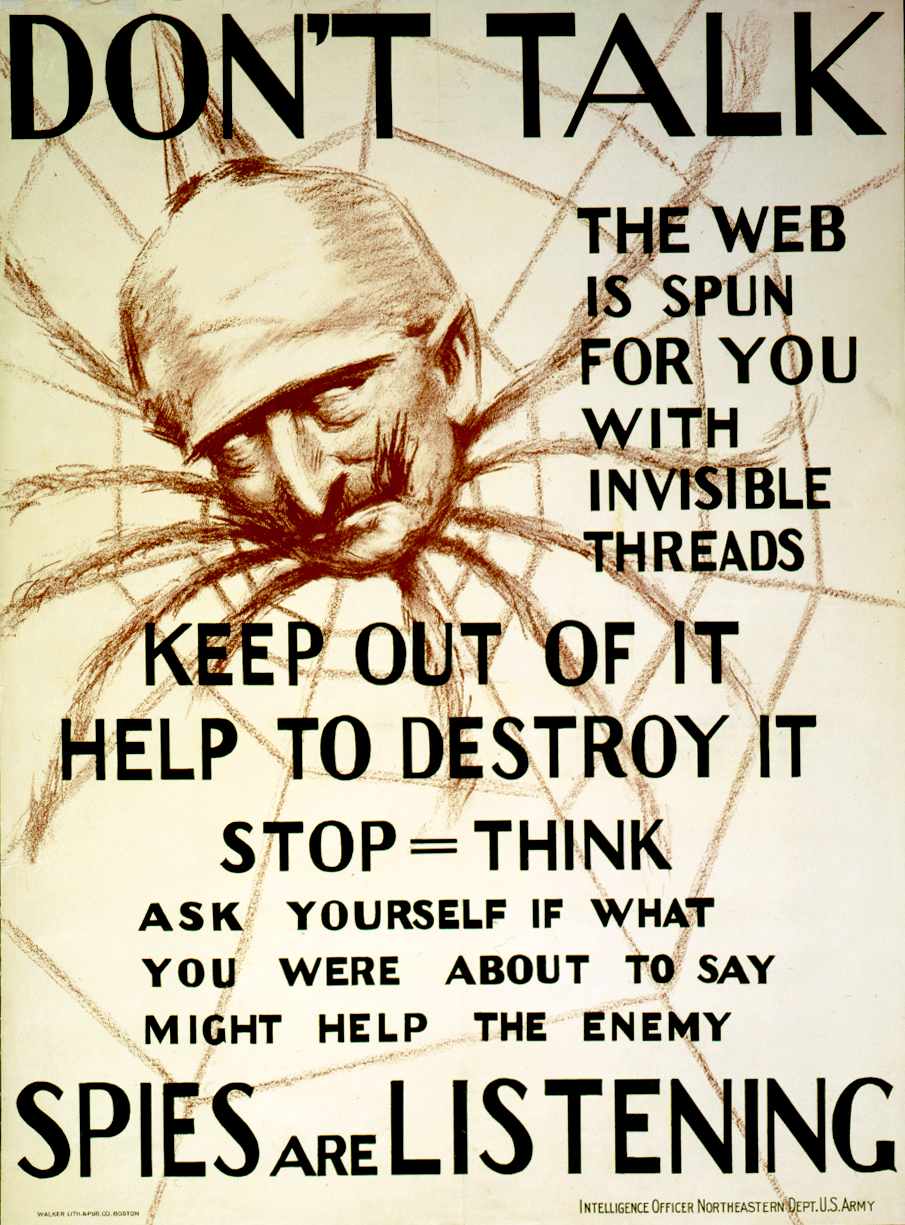

Undercurrents of social discord swelled during WWI. Fearful of German espionage, Congress passed the Trading With the Enemy Act in 1917, giving the president enormous power over foreign commerce and communications. That same year, the state legislature passed a law requiring all "aliens" to register with local police.

The profitable German-American Lumber Company in Pensacola became a target of these WWI era policies. After company president and suspected "enemy alien" H. G. Kulenkampff was arrested by authorities, his business came under control of the federal custodian of alien property, future U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. Palmer’s agency renamed the business American Lumber Company and sold its assets after the war.

In Tallahassee, the chairman of the State Board of Control called for an investigation of Florida State College for Women President Dr. Edward Conradi because of his German parentage. Hamburgers became "liberty sandwiches." Sauerkraut became "liberty cabbage." Teaching the German language, playing German music and even speaking in German were banned in some areas. Unsubstantiated rumors of German infiltration circulated through the state. One anonymous Florida poet vowed "not [to] trade with a German ship that lives by German law."

Racial Inequality During the War

Whereas anti-German sentiment came and went with the war, racism in Florida persisted. Though African-Americans were permitted to donate money at war bond drives, segregation still excluded them from social events. For example, a Jacksonville militia officer prevented a group of African-Americans from participating in a 1918 rally because a white speaker was giving an address. In 1919, a lynch mob in Pace, Florida, accused African-American war veteran Bud Johnson of raping a white woman. After they burned Johnson alive at the stake, a local African-American minister opined that he would have preferred to die in Germany "rather than come back here and die by hands of the people [he] was protecting."

For African-Americans long subjected to the economic inequality and racial violence of the Jim Crow South, increased labor needs during WWI presented new opportunities elsewhere. As early as 1916, companies like the Pennsylvania Railroad and New York Central started recruiting African-American labor in Florida. Between 1916 and 1920, over 40,000 African-Americans left Florida’s northern region, where black populations were the highest in the state. They sought higher wages and fairer treatment in northern and western industrial cities. A faction of local African-American leaders protested the migration, staying in Florida to organize for fair labor and voting rights in the South.

Guarding the Homefront

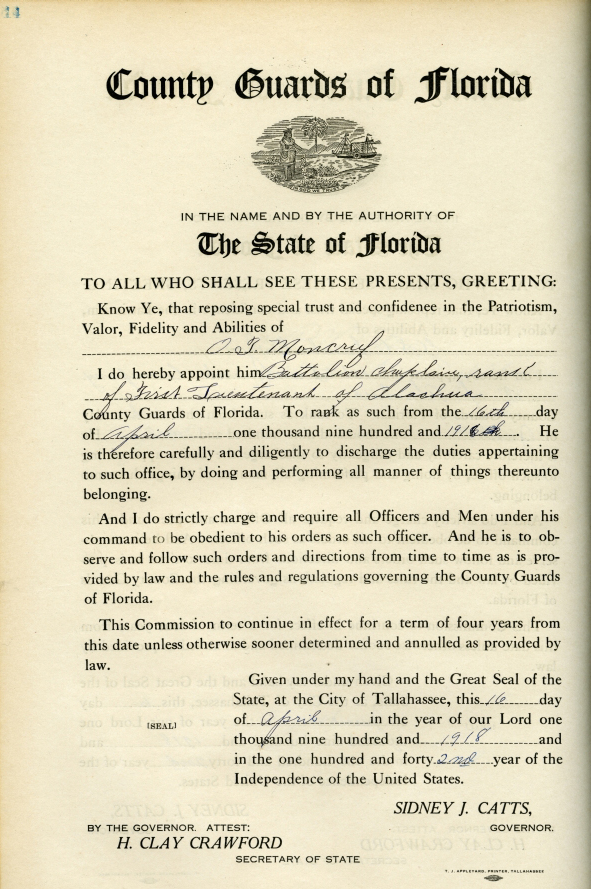

As the war carried on, tens of thousands of Floridians left the state for military service, and the charge of maintaining public safety fell on those remaining at home. After all 2,000 members of the Florida National Guard federalized in early 1917, the Legislature authorized each county to establish their own County, or "Home," Guard units as temporary reserve forces.

Document commissioning officer from Alachua County. Search the County Guard Commissions, 1917-1919.

The law stipulated that individual county governments, not the state, held authority over the militias. An additional caveat allowed only white males between the ages of 16 and 25 to join. Four hundred eighty-four men were commissioned for duty. Except for a few incidences in Hillsborough, Suwanee and Polk counties, the guards saw little action during the war and disbanded shortly thereafter. The University of Florida, the only publicly funded higher education institution for white males in the state, offered a Reserve Officer Military Training Program for the 1918-1919 school year. State lawmakers also temporarily added basic military training classes to the high school curriculum.

Women on the Homefront

While Home Guard units limited participation to white men, Florida women of all races and social strata worked and volunteered on the homefront. Though it had a little over 100 local chapters nationwide in 1916, Red Cross membership significantly expanded to meet the demands of war, and dozens of new chapters opened in Florida by 1920. Members trained as nurses, organized liberty bond drives, knitted socks and sweaters for soldiers, rolled bandages, made comfort bags and disseminated public health information. The Junior Red Cross opened numerous branches at grammar schools in Florida, giving children the opportunity to do their part in the war as well.

Every Monday, the Jacksonville chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union delivered flowers, cans and prohibition literature to soldiers in training at Camp Johnston. They did the same for the families of fallen veterans and even went so far as to provide books and other resources in support of "trench war orphan[s]." The Young Women’s Christian Association established 50 "hostess houses" at training camps throughout the country, including one at Camp Johnston and one at Carlstrom Airfield. Hostesses created a homey yet structured environment for soldiers to meet with their "sweethearts" and other family members.

The women’s club movement in Florida also organized in support of the war. Their contributions mirrored much of the Red Cross’ initiatives, though they focused less on medical training and more on social action. May Mann Jennings headed the Florida Federation of Women’s Clubs during the war.

In Tallahassee, the Florida State College for Women hired the school’s first dietician to address food shortages and develop strategies for conservation. New courses in canning, nursing and knitting were added to the curriculum, and all students participated in on-campus liberty loan drives.

Mary McLeod Bethune presided over the segregated Florida Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs from 1917-1924. Eartha White chaired this state club organization and also worked with the War Camp Community Service, which provided recreation and other services to soldiers. At a meeting of the Council on National Defense at the White House, Eartha White was the only African-American in attendance. Though met with lukewarm response, African-American women like White and Bethune organized efforts to integrate black nurses into white Red Cross units.

Prior to the war, men dominated factory and retail jobs, but with a significant portion of them deployed, women took those traditionally male positions. During this period, Florida organizers Bethune and White recognized the particular vulnerabilities of African-American women doing the "unfamiliar work of elevator girls, bell girls in hotels, and chauffeurs." The pair established the Mutual Protection League for Working Girls to advocate for the labor interests of young African-American working women during the war. Cited as a direct "byproduct of war," the Florida-based program was so successful that one observer suggested it become a model for "every city and hamlet in the country."

Fighting for Suffrage

Whether they were working for wages or mobilizing volunteers, women in Florida experienced an increased level of public visibility due to their homefront efforts during WWI. Since 1913, the Florida Equal Suffrage Association had repeatedly, but unsuccessfully, lobbied the state legislature for the vote. In the summer of 1917, 10 members of the National Woman’s Party, including Mary Nolan of Jacksonville, picketed in front of the White House. Playing into President Wilson’s WWI rhetoric of global democracy, their signs asked, "How long must women wait for liberty?" When police arrested Nolan and the other protesters, the Florida suffragist confessed, "I am guilty if there is any guilt in demanding freedom." Women from all over the country continued to agitate and organize for suffrage. In 1920, the 19th amendment became law and granted voting rights to white women — poll taxes, literacy tests and voter intimidation would effectively disenfranchise the majority of Florida’s African-American population until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Listen: The Folk Program

Listen: The Folk Program