A Guide to Civil War Records

at the State Archives of Florida

The purpose of this guide is to identify and describe the state, federal, and private records pertaining to Florida’s Civil War era (1860-1865) housed at the State Archives of Florida. We hope this guide will assist and promote research into this time period.

Florida and The Civil War: A Short History

By Dr. R. Boyd Murphree

Florida’s role in the American Civil War spanned the entire conflict. From the earliest days of secession in January 1861, when war threatened to break out in Pensacola, to the final surrender of Confederate forces in Florida in May 1865, Floridians experienced all aspects of the war that the South faced as a whole: economic hardship, naval blockade, internal dissension, battle, and final defeat. The purpose of this guide is to identify and describe the Civil War collections and publications available to researchers at the State Archives of Florida and the Florida Collection of the State Library. The following short history provides an overview of the Civil War in Florida and the service of Floridians in the war outside of the state.

Florida Secedes

The catalyst for the secession of Florida was the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency of the United States in November 1860. Fearful that Lincoln and the Republican Party would seek to abolish slavery and thereby destroy the traditional economic and social order of the South, Florida secessionists, led by Governor Madison Starke Perry, called for the state to arm itself in preparation for secession from the United States and the creation of an independent Southern confederacy. The legislature met in regular session on November 26 and voted to call for the election of delegates to a state convention that would convene in January 1861 to decide for or against secession. Every delegate elected to the Convention of the People of Florida [Series S 540] that assembled at Tallahassee on January 3, 1861, supported secession. Their main concern was not whether to secede, but when. The more moderate delegates, known as “cooperationists,” wanted to delay secession until several southern states were ready to leave the Union together. Radical or “fire-eater” delegates demanded Florida’s immediate withdrawal from the United States. The radicals won the debate: the convention passed an ordinance of secession on January 10. The next day, the convention assembled at the state capitol to sign the Ordinance of Secession, which declared Florida’s decision to dissolve its association with the United States and become “a Sovereign and Independent Nation,” making Florida the third state to leave the Union behind South Carolina and Mississippi.

Military Preparations

Military concerns dominated state affairs from the earliest days of Florida’s secession. Even before the formal declaration of secession Florida moved to prepare its defenses. During an extended session from November 26, 1860, to February 14, 1861, the legislature passed a bill to reorganize the state militia, agreed to raise two infantry regiments and one cavalry regiment, and appropriated $100,000 for the purchase of arms and ammunition. On January 4, 1861, the first day of the secession convention, radical members of the convention met in private to authorize Governor Perry to seize federal military sites within the state. Governor Perry ordered state troops to seize the federal arsenal at Chattahoochee and Fort Marion at St. Augustine. Florida troops easily occupied the two undefended installations but failed to secure the more strategic federal positions at Key West, Dry Tortugas, and Pensacola, where Union troops remained in possession of Forts Taylor, Jefferson, and Pickens respectively.

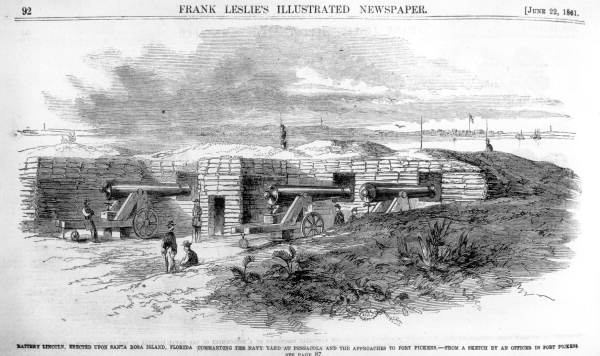

Fort Pickens became the focus of particular concern between North and South as secessionist troops from Alabama and Mississippi rushed to Pensacola to reinforce the small force of Florida militia opposing the Union garrison at the fort. Similar to the situation at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, the military confrontation at Fort Pickens threatened to unleash civil war. The fact that the first shots of the war did not come from Florida was due to the South’s lack of a national government to coordinate strategy among the seceding states (the Confederate government did not exist until February 1861) and the hope that negotiations might secure Fort Pickens for Florida without bloodshed. When war finally came at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, the standoff at Fort Pickens continued, but receded in importance as the focus of the war shifted to the front in Virginia. Despite a Confederate assault on Santa Rosa Island—the site of Fort Pickens—on October 9, 1861, the fort remained in Union hands throughout the war.

Florida Becomes a Confederate State

As Southern militias gathered in Pensacola during the first weeks of the siege of Fort Pickens, Florida, as one of the early seceding states, sent delegates to the constitutional convention that assembled on February 4, 1861, in Montgomery, Alabama, to establish the Confederate States of America. The convention produced a provisional constitution and government headed by Jefferson Davis of Mississippi as president and Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia as vice president. On March 11 the convention made the constitution permanent and the provisional government, which relocated to Richmond after Virginia seceded, dissolved within a year. Davis and Stephens, who were reelected to their offices in November 1861, were inaugurated as the chief executives of the permanent Confederate government on February 22, 1862.

By the end of 1861, some 5,000 Floridians had joined the military forces of the Confederate States.

Florida participated in all of these political developments. On February 26, 1861, the secession convention in Tallahassee approved the passage of the provisional Confederate constitution and ratified the final version on April 13. The convention also endorsed the ticket of Davis and Stephens as the Confederacy’s chief executive officers and revised Florida's constitution to recognize Florida's membership in the Confederate States.

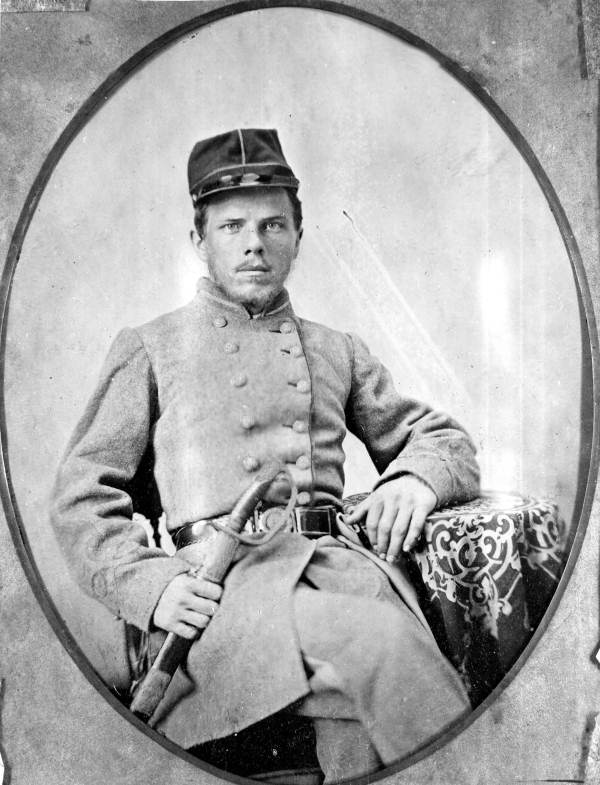

The First Florida Regiments

Weeks before the convention ended, however, enthusiasm for secession in Florida produced thousands of volunteers for the newly created state units and the Confederate army, which quickly absorbed the state regiments for service in and outside of Florida. The First Florida Regiment was Florida’s initial infantry regiment and the first Florida unit to enter Confederate service when it joined Confederate forces in April 1861 in their siege of Fort Pickens at Pensacola. In July, the Second Florida Regiment formed and left the state for Virginia. Florida produced two more infantry regiments, a cavalry battalion, and a number of independent infantry, artillery, and cavalry companies in 1861. By the end of the year, some 5,000 Floridians had joined the military forces of the Confederate States. While the vast majority served in the Confederate army, a small number served in the Confederate navy, which was headed by Stephen Russell Mallory, one of Florida’s prewar senators. Mallory served as Confederate States Secretary of the Navy for the duration of the war.

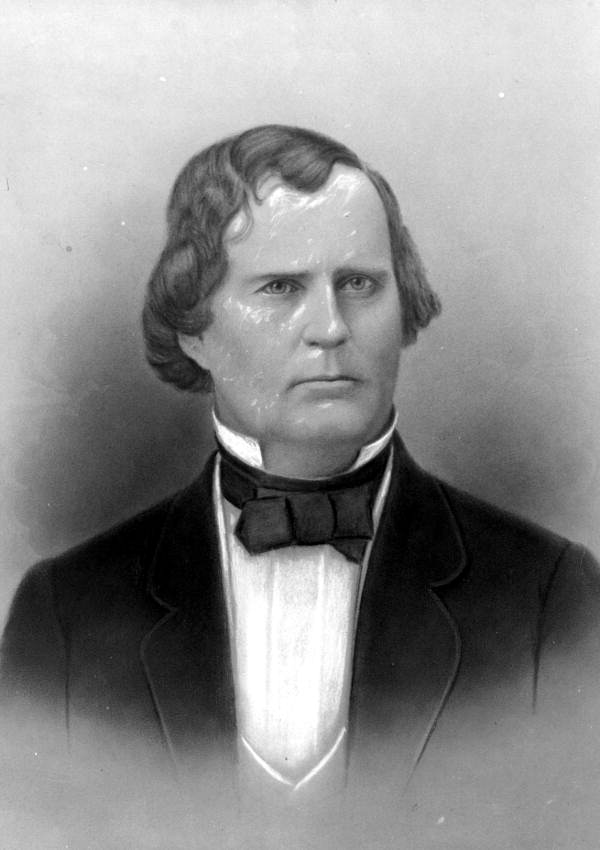

Governor Milton

Executive leadership of the war in Florida passed to John Milton, who succeeded Madison Starke Perry as governor on October 7, 1861. Although elected in October 1860, Milton, a successful lawyer and planter from Jackson County, could not assume his office for a year as called for by an amendment to Florida’s 1838 constitution, which was still in force when Milton ran for governor. When he did take up his office, however, Milton proved to be energetic chief-of-state who took seriously his role as commander-in-chief of Florida’s military forces.

During the first months of his administration, Milton bombarded the Confederate government with complaints about Richmond’s seeming indifference to the poor state of Florida’s defenses and the Confederate War Department’s willingness to accept individuals and volunteer units into the Confederate army without obtaining prior permission from the state. Milton saw this practice as a violation of states’ rights. He protested that direct national recruitment ignored Florida’s prerogative to raise and control its own military forces as well as his authority as commander-in-chief to command those forces. While Milton continued to protest any Confederate actions that he believed infringed on Florida’s sovereignty, he grew to temper his objections with the realistic attitude that while Confederate policies such as conscription, for example, violated states’ rights, such policies had to be tolerated in order for the seceding states to secure a common victory in the war for their independence. Jefferson Davis and successive Confederate secretaries of war repeatedly praised Milton for his loyalty and willingness to sacrifice his state’s resources for the Confederate cause.

The Union Attacks Florida

Those sacrifices intensified in 1862 as the Union launched its first attacks on Florida. The U.S. Navy wanted to control ports in Florida to support a naval blockade of the South. Federal troops landed on Amelia Island and captured Fernandina on March 4, 1862. A week later, St. Augustine fell to the North, whose troops then occupied Jacksonville on March 12. All of these actions were unopposed as Confederate forces withdrew from the state’s east coast under orders from General Robert E. Lee [telegraphic dispatch from 1861], the commander of Confederate forces along the Atlantic coasts of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida. Lee, who was not yet a famous or popular general, believed that an interior defense was the only viable strategy given Union naval superiority and the small number of Confederate troops available for the defense of Florida’s immense coastline.

In any case, Lee had little choice in the matter. The Confederate War Department ordered the withdrawal of virtually all of the Confederate troops in Florida for duty in the West, where the Confederacy had suffered serious defeats in February 1862 with the loss of Forts Henry and Donelson in Tennessee. The withdrawal of Confederate forces from Florida to other theatres, combined with the limited nature of the Union landings in Florida, created stalemate in East Florida for the next two years. Less than a month after they landed, the Federals evacuated Jacksonville; however, they remained in Fernandina and St. Augustine for the rest of the war. Union troops returned to Jacksonville three more times during the war: October 6-9, 1862, in the wake of a successful Federal effort to reopen the St. Johns River to Union gunboats; March 10-29, 1863, when a Federal force consisting of the 1st and 2nd South Carolina regiments, U.S.C.T. (United States Colored Troops) occupied Jacksonville as part of a campaign to free slaves and encourage Unionism in East Florida; and finally in February 1864 during the Federal offensive that ended in the battle of Olustee, which, despite being a Union defeat, left Jacksonville in Federal hands until the end of the war.

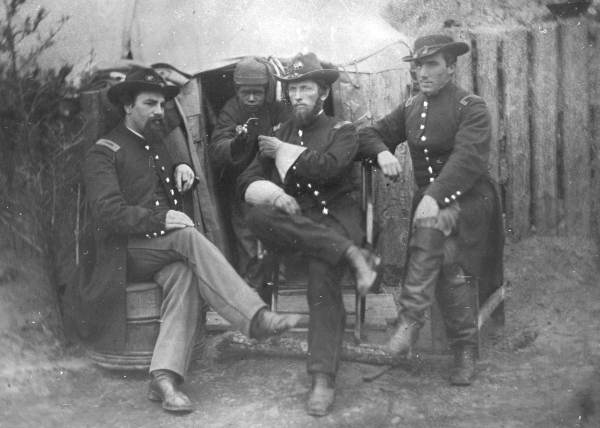

Florida Regiments and the War in the East

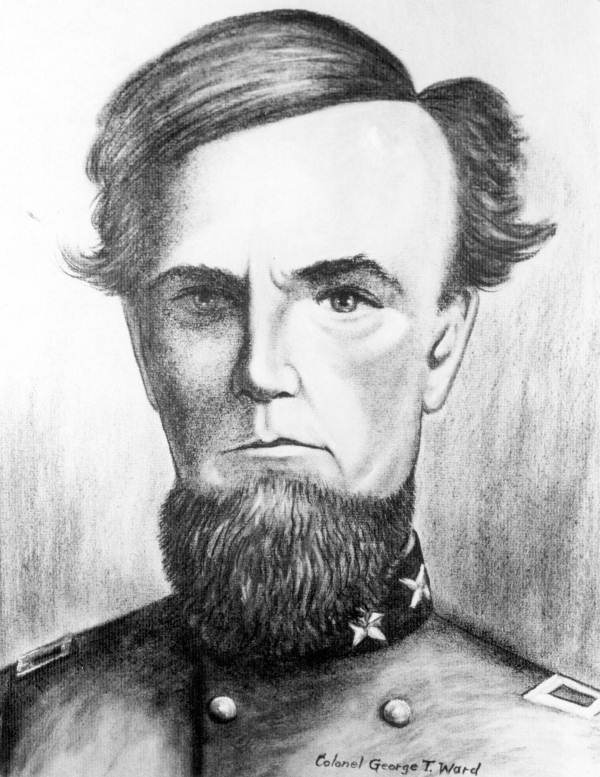

Florida met the Union incursions of 1862 to 1865 with only a handful of state and Confederate troops. Most of the state’s Confederate soldiers never fought on their home soil. Instead, their regiments served in the Confederate armies deployed in the major theatres of operations in Virginia and the West (Tennessee, Mississippi, and Georgia). The Second Florida saw its first actions in Virginia as one of the defending regiments in the siege of Yorktown in April 1862 and in May during the Battle of Williamsburg, where the regiment lost its commander, Colonel George T. Ward, who was killed during the fighting. Following the Confederate withdrawal from the Virginia Peninsula and the ensuing battles on the outskirts of Richmond, the Second Florida was joined in Virginia by the Fifth and Eighth Florida infantry regiments. All three Florida regiments fought in the Second Battle of Manassas (or Second Bull Run) in August 1862 as part of the Army of Northern Virginia under General Lee. In September, the Florida regiments moved with Lee’s army into Maryland and engaged in what has been called the bloodiest single day in U.S. history, the Battle of Antietam, on September 17, 1862.

After the Antietam defeat, Lee reorganized the Army of Northern Virginia, including the three Florida regiments, which now formed a single brigade under the command of Brigadier General Edward A. Perry, a future governor of Florida. During 1863, the “Florida Brigade” participated in the Army of Northern Virginia’s greatest triumph and its worst defeat: the Battle of Chancellorsville on May 3 and the Battle of Gettysburg on July 1-3 [letter describing Florida Brigade's retreat from Gettysburg]. Decimated in the fighting at Gettysburg, the Florida Brigade remained a unit on paper but battlefield losses reduced the brigade to little more than the size of one regiment.

In 1864, the Ninth, Tenth, and Eleventh Florida infantry regiments joined the Florida Brigade in Virginia. The reinforced brigade, now under the command of General Joseph Finegan, fought in the battles of attrition that characterized General Ulysses S. Grant’s campaign against the Army of Northern Virginia in the summer of 1864. Retreating with the remnants of Lee’s army after the collapse of the Confederate positions around Richmond, the surviving members of the Florida brigade surrendered along with the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox on April 9, 1865.

Florida Regiments and the War in the West

The hard-fought service of Florida units in Virginia had its counterpart in the West, where six Florida regiments fought as part of the Confederate armies engaged in battles for control of territory ranging from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River. Consisting of one cavalry regiment and five infantry regiments—about 6,000 out of the total of 15,000 Floridians who fought for the Confederacy during the war—the following Florida units saw service in the West: the First, Third, Fourth, Sixth, and Seventh infantry regiments, and the First Florida Cavalry Regiment. Men from the First Florida Infantry participated in the Battle of Shiloh on April 6-7, 1862, and the defense of Corinth, Mississippi, in May. All of the Florida units in the West during 1862-1863 eventually served with the Army of the Mississippi (later designated the Army of Tennessee) under General Braxton Bragg or in the Department of East Tennessee headed by General Edmund Kirby Smith, a native of St. Augustine, Florida.

The First and Third Florida infantry regiments participated in the Confederate invasion of Kentucky in August 1862 and joined with the Fourth Florida as part of the Army of Tennessee in the Battle of Murfreesboro from December 31, 1862, through January 2, 1863. A defeat for the Confederacy, Murfreesboro marked the beginning of a series of Union victories over the Confederate forces in the West during 1863. The Florida Brigade of the West (the combined First, Third, and Fourth infantry regiments) made up part of the Confederate army that failed to relieve the Confederate force besieged at Vicksburg, Mississippi: the city surrendered to General Grant on July 4, 1863, a disaster which severed the South west of the Mississippi from the rest of the Confederacy.

All of the Florida regiments stationed in the West participated in one or more of the battles that raged around Chattanooga, Tennessee, from September through November 1863. The Sixth and Seventh Florida and the First Florida Cavalry joined the rest of the Florida Brigade at Chickamauga and fought alongside the Florida First, Third, and Fourth infantry regiments at Missionary Ridge.

During the last year of the war, the Florida units in the West continued to serve with the Army of Tennessee as it fought in the defense Atlanta, attempted to recapture Nashville, and finally retreated into North Carolina, where General Joseph E. Johnston, the commander of the Army of Tennessee, agreed to surrender his forces to General William T. Sherman. The remnant of the Florida Brigade of the West laid down its arms with the rest of General Johnston’s army on May 4, 1865, at Greensboro, North Carolina.

Florida’s Civil War Newspapers

Floridians followed the campaigns of the Florida brigades in the pages of their newspapers. At the beginning of the war, all Florida newspapers gave their support to the Confederate cause. Tallahassee was the site of the state’s most prominent Democratic and Whig newspapers. The Floridian and Journal, a Democratic weekly, was an ardent advocate of secession and the war for Southern independence. Although more cautious about secession, the Tallahassee Florida Sentinel supported the war and the policies of President Davis. Other notable Confederate newspapers in North Florida were the Fernandina East Floridian, the St. Augustine Examiner, and the Cotton States in Alachua County.

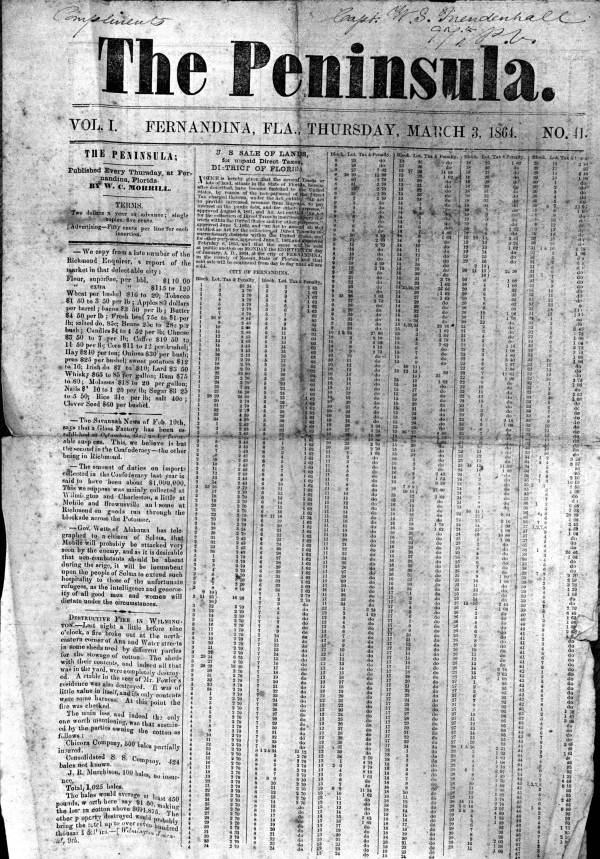

In South Florida, the Key of the Gulf, a Key West newspaper, was staunchly secessionist; however, its advocacy ended in May 1861 when the Federals, who remained in control of Key West, established martial law on the island. The Federal authorities shut down the Key of the Gulf and replaced it with the pro-Union New Era, which remained the principal newspaper in South Florida for the rest of the war. Other Florida Unionist newspapers arose as a result of Federal military successes in the state. Federal occupation of Fernandina and Jacksonville allowed Unionists to eventually establish newspapers in both towns. The Peninsula began publishing in Fernandina on April 18, 1863. In 1864, the Florida Union established itself as a successful weekly and continued to publish after the war as a daily.

Florida Unionists

While Federal troops in Fernandina, Jacksonville, Key West, Pensacola, and other coastal towns provided a secure environment for the operation of the Unionist press in Florida, the continued publication of Union newspapers in Florida reflected the existence of substantial enclaves of Unionist sentiment in the state. The presence of Federal troops on Florida soil combined with growing public dissatisfaction with Confederate conscription and impressment policies to encourage desertion. Several Florida counties in the Panhandle and southwest area of the state became havens for Florida deserters as well as deserters from other Confederate states. Deserter bands attacked Confederate patrols, launched raids on plantations, confiscated slaves, stole cattle, and provided intelligence to Union army units and naval blockaders.

The Union army formed two regiments in Florida: the First Florida U.S. Cavalry and the Second Florida U.S. Cavalry.

Although most deserters formed their own raiding bands or simply tried to remain free from Confederate authorities, other deserters and Unionist Floridians joined regular Federal units for military service in Florida. The Union army formed two regiments in Florida: the First Florida U.S. Cavalry and the Second Florida U.S. Cavalry (Series S 1280). Recruitment for the regiments began in December 1863 and continued into the summer of 1864. The First Florida (US) was organized in Pensacola and operated in West Florida and South Alabama. Meanwhile in South Florida, the Second Florida (US) was organized principally from enlistments at Key West and joined in Union operations along Florida’s western Gulf coast from Key West in the south to St. Andrews Bay in the north. In addition to the First and Second regiments, independent Union units organized in Florida included two company-sized units (the Florida Rangers and the First East Florida Cavalry) as well as several bands of deserter-irregulars.

The War at Home

The deserter issue was one of many internal problems that confronted Confederate Florida during the war. Faced daily with the possibility of receiving news of the death or wounding of a family member or friend, Floridians on the home front also had to cope with constant shortages of food and domestic goods, higher taxes, the possibility of abandoning or losing their homes due to military action, Confederate impressments of agricultural goods, and Federal confiscation of property, including slaves. Before the war, Floridians, like most Americans, had little interaction with government beyond the local level: taxation was minimal, government services few, and military service limited to irregular musters of the state militia.

Civil war brought dramatic change to Americans’ relationship with their state and national governments. In Florida and the other Confederate states, destitution brought on by shortages and the loss of fathers and sons to the battlefront left countless small farm families (the vast majority of the white population) with little means of feeding and clothing themselves. Florida’s state government reacted to the crisis by implementing unprecedented policies to assist the ever increasing number of needy families. The state enacted legislation to allow county governments to raise property taxes to pay for the relief of indigent families of soldiers in their respective jurisdictions. Relief money was used to provide food and clothing for women and children as well as clothing and provisions for the men of poor families who had been called up for military service.

Governor Milton and the legislature also encouraged planters to turn more of their plantation fields to the growth of edible crops rather than cotton, in order to increase food production. One unforeseen consequence of the subsequent rise in corn crops was an increase in alcohol distillation, which some farmers turned to in order to reap profits from the increased wartime demand for whiskey. In 1862, the state, concerned that so much corn was being drunk rather than eaten, banned alcohol production in Florida. Only licensed producers, who found a lucrative market for their product through sales to the Confederate government, could continue to supply alcohol for medicinal purposes and the relief of the South’s overburdened soldiers and sailors.

Conscription and Impressment

Conscription became law in Florida when the Confederate government passed the first of three conscription acts on April 16, 1862.

While many poor Floridians doubtless welcomed state and local assistance, national government policies often met popular resistance. The two Confederate policies which caused the most unrest were conscription and impressment. Conscription became law in Florida when the Confederate government passed the first of three conscription acts on April 16, 1862. The first act called for the enrollment of all white males between the ages of 18 and 35 in the military service of the Confederate States for a period of three years. While most Southerners seemed to accept the military necessity of conscription, just as many resented the inequalities of the first act, which allowed substitution (wealthier men could pay poorer men to serve for them) and allowed planters to exempt overseers on plantations that held twenty or more slaves. By the time the Confederate government organized conscription in Florida (during the summer of 1862), most white males of conscription age in the state were already serving in the Confederate forces.

Given the few men who remained eligible for the draft, Governor Milton believed it would be better if the Confederate government exempted Florida from conscription. Although he expressed this view to President Davis, Milton made it clear to the Confederate president and to the Southern public that he would make every effort to comply with the draft laws. During 1863-1865, Confederate conscript officials scoured the state for eligible men but only managed to obtain a few hundred draftees: the rest of the men (most) were either already in military service or avoiding the draft by hiding out in Florida’s vast, under populated countryside.

The Confederate impressment policy was just as unpopular with Southerners as conscription. In March 1863, the Confederate government passed an impressment law intended to ensure the adequate supply of its military forces. The law authorized impressment agents to locate foodstuffs and other supplies and established fixed prices for the necessary items. Farmers across Florida and throughout the South protested the impressment system, which deprived them of their produce and livestock for payments in increasingly depreciated Confederate scrip.

Wealthier planters also decried impressment when it entailed the loss of valuable slaves to Confederate service. Although the impressment act required agents to pay owners at least thirty dollars a month for each slave employed in work for the Confederate government and called for the reimbursement of owners should a slave be injured or lose his life while working in Confederate service, slave owners were reluctant to give up their slaves for war work: the slaves would no longer be producing for the plantation, and owners might lose expensive slaves to injury or death during their employment on Confederate military projects. The Confederate government, however, was not reluctant to forcibly impress slaves if owners refused to provide slaves for war work.

Slavery in Wartime Florida

In Florida, Confederate authorities used slaves as teamsters to transport supplies and as laborers in salt works and fisheries, two industries that were vital for the continued provisioning of the Confederate army and the survival of civilians at home. Many Florida slaves working in these coastal industries used opportunities presented by the presence of Union blockading vessels and frequent coastal raids by Federal troops to escape bondage. The Union employed many of these escaped slaves on ships or received them into service as soldiers and sailors in the U.S. military.

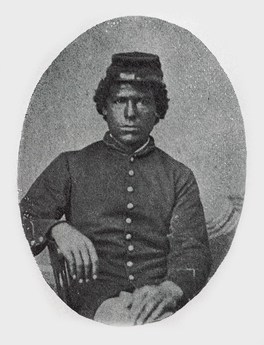

On January 1, 1863, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared freedom for all slaves in Florida and the rest of the South that remained under Confederate control. There were over 61,000 slaves in Florida in 1861. The vast majority of the slave population (70 percent) resided in the counties of Middle Florida (most in Gadsden, Leon, Jefferson, and Madison counties) and one West Florida county (Jackson), where their labor accounted for 85 percent of the state’s cotton production as well as a wide variety of other agricultural crops. In East Florida, most slaves lived in Alachua and Marion counties, where plantations also produced significant cotton crops. The number of slaves on plantations varied from small plantations (less than 500 acres and fewer than 20 slaves) to large plantations that ranged in slave populations from 20 to over 200. Beginning in 1862, Union military activity in East and West Florida encouraged slaves in those areas to flee their owners in search of freedom. Of those slaves who reached the relative safety of Union controlled enclaves, more than a thousand enlisted in the military service of the United States. Escaped and freed slaves provided Union commanders with valuable intelligence about Confederate troop movements and passed on news of Union advances to the men and women who remained enslaved in Confederate controlled Florida. Planter fears of slave uprisings increased as the war went on.

Florida and the War in 1864

By 1864, however, there was little difference in the military situation in Florida from what it had been in the spring of 1862. The Union continued to control Key West, Pensacola, St. Augustine, and Cedar Keys—Federal troops occupied Cedar Keys as early as January 1862. Confederate strategy in Florida remained concentrated on blocking Union access to the interior, protecting the coastal salt works, and ensuring the supply of Florida beef cattle to the Confederate army. It was Florida’s importance as a food source for the Confederacy and its burgeoning significance in Northern presidential politics that led to the Union’s decision to launch what would prove to be its largest military expedition in the state during the war.

On February 7, 1864, Federal troops once again captured Jacksonville. This time, however, the Federals were determined to hold the city and push into the interior. The objectives of the Union campaign were to gain control of agricultural resources (especially cotton, timber, lumber, and turpentine) in East Florida, recruit slaves for service as troops, interrupt the supply of Florida beef cattle to Confederate armies out-of state, disrupt the Florida railroad system, and facilitate the restoration of Florida to the Union. The last objective was the result of Florida’s potential as a source of electoral votes in the upcoming presidential election of 1864. If Florida could be restored to the Union before the Republican nominating convention, either President Lincoln, who would be running for reelection, or Secretary of the Treasury William P. Chase, who hoped to secure the Republican nomination himself, could benefit from Florida’s votes.

The Union’s East Florida Expedition

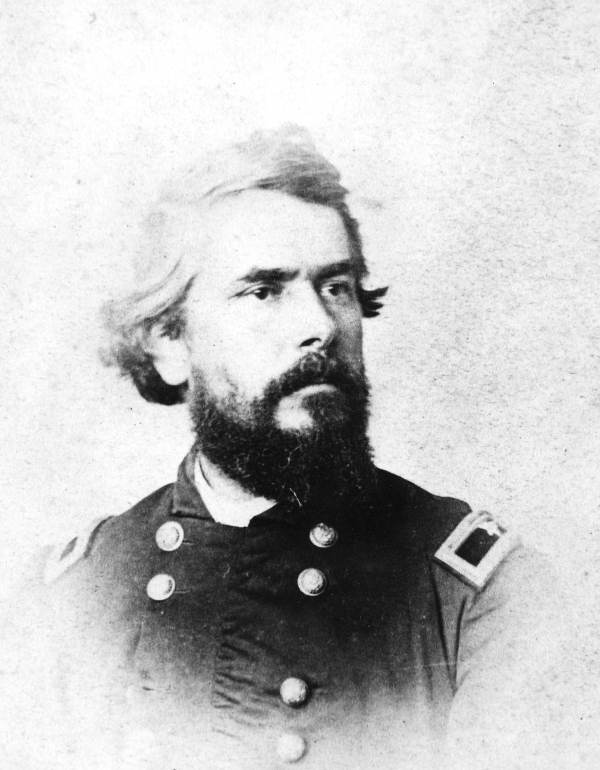

Major General Quincy A. Gillmore, the commander of the Union army’s Department of the South, which was the headquarters responsible for Federal operations in Florida, gave the command of the East Florida campaign to Brigadier General Truman B. Seymour, who led the Federal expedition that landed at Jacksonville on February 7. Seymour’s command consisted of some 6,000 troops organized into four brigades (three infantry, one cavalry) and supporting artillery units. After occupying Jacksonville, Federal cavalry conducted raids towards Lake City and Gainesville. The raiders reached the outskirts of Lake City on February 11 but retreated after encountering Confederate forces blocking their advance to the west.

Cautious after the Federal repulse at Lake City, General Seymour consolidated his position around Jacksonville, which included control of the important railway junction at Baldwin, a community about twenty miles west of the port. Now confident that Jacksonville was securely under Federal control, Seymour decided to move the bulk of his small army, about 5,500 men, from Baldwin towards Lake City. He hoped to push past Lake City to destroy the railroad bridge of the Pensacola and Georgia Railroad at Columbus on the Suwannee River. Seymour’s force began its march for Lake City on the morning of February 20.

The Union landing in Jacksonville and subsequent advance against Lake City created panic in Tallahassee. Governor Milton telegraphed the Confederate war department that “all will be lost” in Florida unless Richmond immediately dispatched reinforcements to the beleaguered state. At the time of the Union landing in Jacksonville, there were only some 1,200 Confederate troops in the Department of East Florida, the Confederate command responsible for the defense of Florida east of the Suwannee River. Brigadier General Joseph Finegan, the Confederate commander in East Florida, ordered his scattered forces to concentrate at Lake City, where he planned to block the Union advance. If he had been forced to rely solely on the few troops available to him in Florida, however, Finegan would not have been able to withstand the Union advance.

Luckily for Finegan, General Pierre G. T. Beauregard, who had overall responsibility for the command of the Confederate Atlantic Coast south of North Carolina, recognized the threat the Union expeditionary force posed to the continued supply of food from Florida to his and other Confederate armies and potentially to Florida’s future in the Confederate States. Both Beauregard and Governor Milton feared the Union advance from Jacksonville might be only one wing of a Union offensive against Florida. They saw the potential for disaster should the Union follow up the Jacksonville landing with a landing on the Gulf at St. Marks and an attack on Tallahassee. Beauregard therefore rushed reinforcements from South Carolina and Georgia to East Florida.

The Battle of Olustee

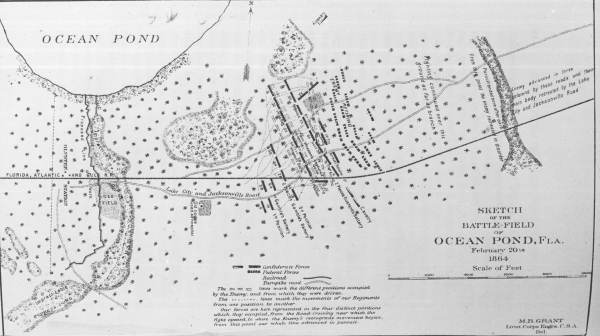

The Battle of Olustee (or Ocean Pond) was the largest and bloodiest battle fought in Florida during the Civil War.

When Seymour’s brigades began their march on the morning of February 20, Finegan had over 5,000 troops assembled at Olustee, a station of the Florida, Atlantic and Gulf Central Railroad located ten miles east of Lake City. Most of the Confederate force consisted of two brigades of Georgia troops under the command of Brigadier General Alfred H. Colquitt and Colonel George P. Harrison. Finegan positioned his force in a mile and a half long line running from Ocean Pond (a large, bowl-shaped lake) in the north to a large swamp south of the railroad. When his cavalry reported the Union advance on the morning of the 20 th, Finegan ordered a portion of Harrison’s brigade and eventually all of Colquitt’s brigade plus supporting artillery to advance towards the oncoming Federals, engage them, and draw them towards the prepared defensive positions at Olustee.

Colquitt and Harrison’s men were fully engaged with Seymour’s troops by the afternoon. The Georgians were unable to fall back to the Confederate defensive works at Olustee. Instead, the battle occurred in an open pine barren flanked by swamps about two miles east of the main Confederate defensive works. During the first stage of the battle, confused orders exposed two Union regiments to intense Confederate musket and artillery fire that resulted in heavy Federal casualties and the rout of Colonel J. R. Hawley’s brigade, the first infantry brigade in the Union line of advance. The breakup of Hawley’s brigade allowed a Confederate advance all along the line. Union resistance stiffened, however, and hard fighting continued into the late afternoon. By this time, the rest of Finegan’s army arrived on the battlefield and managed to push back the Union flanks.

Faced with renewed Confederate pressure, General Seymour decided to withdraw his exhausted force. He deployed his reserve brigade, which consisted of the famous 54th Massachusetts regiment as well as the 35th U.S. Colored Infantry. The two black units managed to delay the Confederate advance long enough for Seymour to execute his withdrawal. As night fell, the Union army was in full retreat towards Jacksonville. A poorly executed Confederate pursuit failed to hinder the Federal retreat. All of Seymour’s army reached the Federal lines around Jacksonville by February 22.

The Battle of Olustee (or Ocean Pond) was the largest and bloodiest battle fought in Florida during the Civil War. Given the small numbers of troops involved, overall casualties for the battle were high: the Confederates lost 946 men (93 killed, 847 wounded, and 6 missing); the Federals lost 1,861 men (203 killed, 1,152 wounded, and 506 missing). Based on the percentage of loss (29.9 percent) for the force involved, the Union casualty rate at Olustee was one of the highest for any battle of the war. The large number of Union missing included dozens of wounded or captured black soldiers, whom the Confederates, angry at seeing former slaves fighting as Union soldiers, killed out of hand. Although the Federal expedition succeeded in recruiting a number of slaves for the Union army and disrupting the movement of Confederate foodstuffs out of Florida, the defeat at Olustee ended any Union plans to bring Florida back into the United States in 1864. For the South, the battle temporarily boosted morale in what was otherwise a bleak winter for Confederate military fortunes. Florida remained in the war but returned to its pre-Olustee status as a low priority area for the Confederacy.

Further Fighting in Florida

Olustee may have been the largest Civil War battle fought in Florida, but it was not the last. In September 1864, Brigadier General Alexander Asboth, the commander of Union forces in West Florida, led a raid from Pensacola to Marianna in Jackson County. Aware of the Federal raiders, the local Confederate command hastily assembled a “Cradle and Grave Company” of militia composed of boys under 16 and men over 50 to defend Marianna. The resulting engagement was brief but intense: Confederate losses included 10 killed and over fifty captured, while the Union force suffered 8 dead and 19 wounded, including General Asboth, who was shot in the face.

The last significant battle of the war in Florida came in March 1865, when a Union force landed on the Gulf and threatened Tallahassee. After landing near St. Marks on March 4, 1865, Brigadier General John Newton and some 600 Union troops marched to the town of Newport with the intention of crossing the St. Marks River and attacking the port of St. Marks and its Confederate-held fort from the rear. Confederate forces in the area destroyed the bridge at Newport which prevented a Union crossing of the St. Marks at that point. The next day, General Newton and his force marched to Natural Bridge, where they hoped to cross the river and proceed to St. Marks. On the morning of March 6, Newton tried to move across the St. Marks at Natural Bridge, but a Confederate force positioned on the opposite bank blocked his crossing. The Confederates, commanded by Brigadier General William Miller, consisted of a motley collection of regulars, militia, and a company of cadets from the West Florida Seminary—one of two state military academies in Florida (the East Florida Seminary was in Gainesville)—in Tallahassee, which was about twelve miles north of Natural Bridge. Miller’s Confederates prevented several Union attempts to flank their position. Unable to dislodge the Confederates, Newton withdrew from Natural Bridge and retreated to the coast, where the Federal flotilla evacuated his force.

The Last Days of Confederate Florida

Although Confederate Florida proclaimed Natural Bridge a great victory, celebration in Tallahassee was short-lived. Three weeks after the battle, on April 1, 1865, Governor John Milton took his own life at his plantation home in Jackson County. While he left no explanation for his suicide, Milton was physically and mentally exhausted after leading his state during three and a half years of war. The prospect of Confederate defeat and Union occupation of Florida was too much for him. A week after Milton’s death, on April 9, 1865, General Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to General Grant following the Union general’s capture of Richmond. The end of the Confederate experiment was now at hand. For Florida, the end came on May 10, 1865, when Union Brigadier General Edward M. McCook arrived in Tallahassee to accept Confederate Major General Samuel Jones’ surrender of all Confederate forces in Florida. In a formal ceremony held in Tallahassee on May 20, McCook ordered the United States flag to be raised over the Capitol. Florida’s civil war was over.

Dr. R. Boyd Murphree, in addition to his work as a reference archivist at the State Archives of Florida, is a Florida historian and specialist on the Civil War. He received his B.A. from Stetson University, and his M.A. and Ph.D. from Florida State University.

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program

Listen: The Bluegrass & Old-Time Program