A Guide to Researching the Territorial Era

at the State Archives of Florida

This guide describes the variety of published and unpublished resources available for researching Florida's tenure as a United States territory prior to statehood (1821-1845). Some of the resources have been fully digitized and are available online. Others may be viewed by visiting the State Library & Archives' research facility in Tallahassee. Contact us with any questions about the collections discussed in the guide.

A Territorial Era Primer

Florida was ceded to the United States by the Adams-Onis Treaty, signed February 22, 1819 by representatives of the U.S. and Spain at Washington. Following ratification of the treaty by both parties, U.S. military authorities proceeded to Pensacola and St. Augustine and took official possession of the territory in July 1821.

Florida was a large addition to the U.S., strategically placed at the gateway to the Caribbean. It came with some challenges, however. Although the Spanish had maintained settlements in Florida since the 16th century, they had created very little infrastructure to support a local economy. The only towns of any consequence in this new province of over 60,000 square miles were located at Pensacola, St. Augustine, and Fernandina. Much of the interior was inhabited mostly by Native Americans.

These challenges nothwithstanding, American settlers began moving into Florida, eager to take advantage of the abundant inexpensive land. Plantations, farms, and the businesses necessary to support a fledgling frontier society began appearing across the northern part of the territory. Enterprising local leaders planned capital improvements such as canals and railroad lines to facilitate commerce. In 1826, Congress appropriated $20,000 for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to study routes for a canal connecting the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. Neither this nor another attempt in 1832 led to any tangible progress on a canal plan. Florida's first steam-powered railroad opened between St. Joseph and Lake Wimico in 1836; a mule-powered line was completed between Tallahassee and Port Leon the same year.

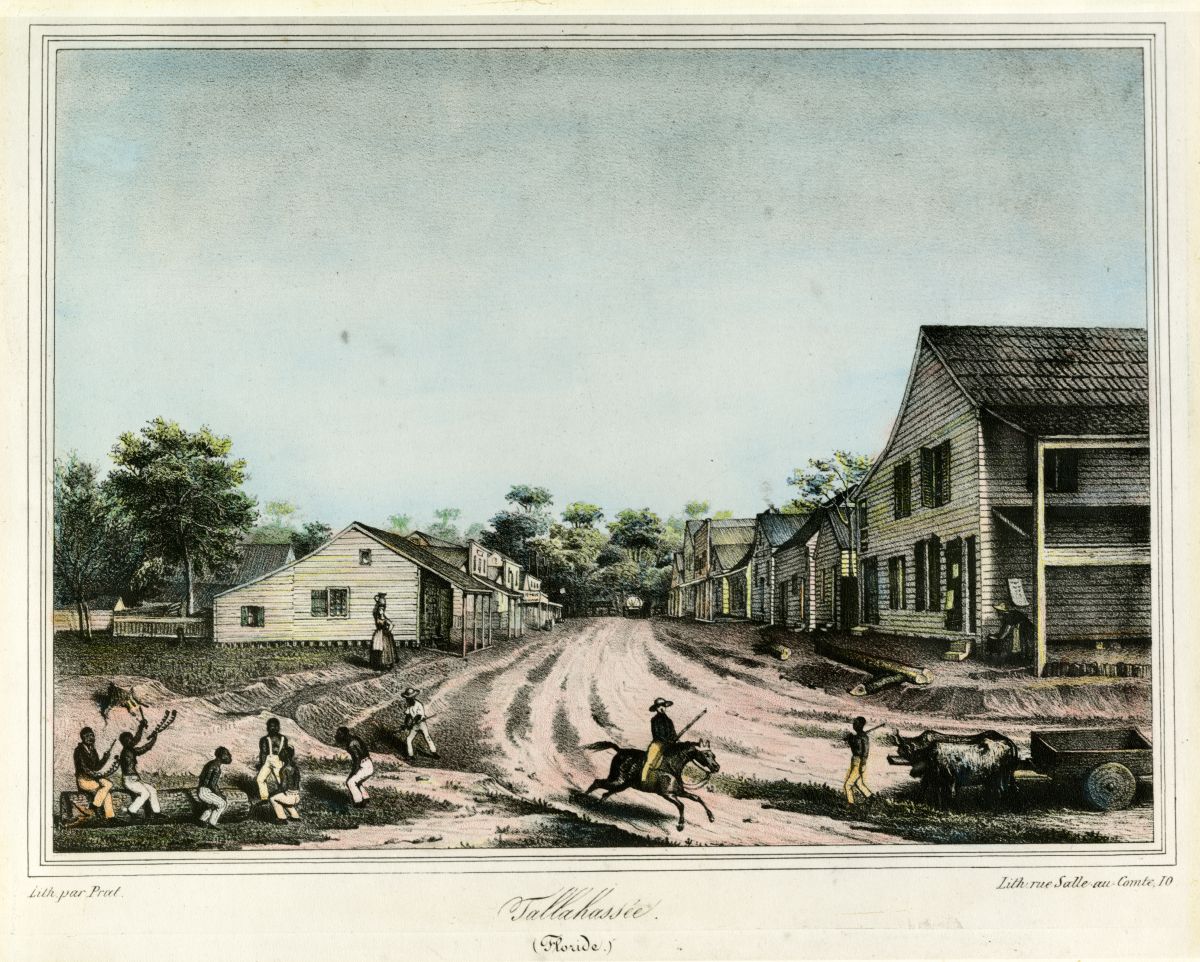

Meanwhile, the territorial government had plenty of administrative challenges to occupy its time. Pensacola and St. Augustine were separated by almost 400 miles, connected only by the primitive Old Spanish Trail. Most travelers chose to go between these two points by boat rather than over land. In 1823, Governor William Pope DuVal appointed Dr. William H. Simmons of St. Augustine and John Lee Williams of Pensacola to select a site for a new territorial capital somewhere between the Suwannee and Ocklockonee rivers. The two commissioners ultimately recommended a former Native American settlement at Tallahassee, and Governor DuVal proclaimed this the new territorial capital in 1824.

Attracting settlers and preparing to sell them land was another governmental priority. The United States had agreed to recognize the hundreds of land grants given to private individuals by the Spanish government during its tenure in Florida, but that still left millions of acres of land in the public domain. Government surveyors quickly began surveying the territory into a uniform grid system, using a starting point southeast of the Capitol in what is now Tallahassee's Cascades Park. As land was surveyed into townships and sections, it was made available for sale or auction at government land offices in Tallahassee and elsewhere.

As with any new government, the territorial legislature had its share of questions to resolve over policies regulating commerce, education, and social institutions. Banking was perhaps one of the most contentious issues facing the assembly. Members of Florida's planter class were eager to expand their farms and develop new infrastructure, but they needed capital to do it. The nearest banks of any consequence were in New Orleans and Charleston, which made financing new projects difficult. The solution, many Floridian planters believed, was for Floridians to establish their own banks. Disagreements emerged between legislators and the governor over how to support these banks, and the Panic of 1837 complicated matters even further.

The ultimate goal for Florida's territorial government was for the new province to be admitted into the U.S. as a state, which would mean better representation in Congress and immense grants of public lands for internal improvement. Floridians were deeply divided, however, over the terms on which they would join the Union. Some citizens hoped to wait until Florida's population was large enough to form two states. This, they hoped, would aid the South in its Congressional battles over slavery and other regional concerns. Some Floridians in the Panhandle favored annexing their territory to Alabama rather than becoming a new state altogether. Citizens in both eastern and western Florida disliked the costs of supporting a state government, which could only be met by an increase in taxes. Militating against these concerns was the spectre of the Second Seminole War, which underscored Florida's dependence on the federal government for protection.

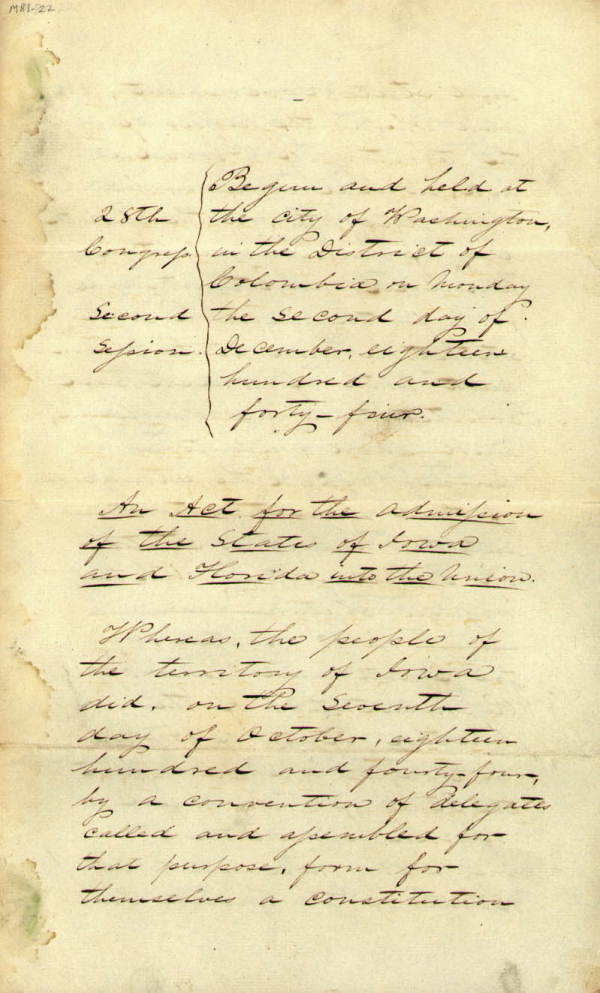

Sufficient support existed by 1838 to call a constitutional convention. Delegates met at the enterprising young seaport of St. Joseph on the Gulf coast to hammer out the details of Florida's first state constitution. On January 11, 1839, the delegates completed their work and sent the finished document up to Congress with a memorial asking that Florida be admitted as a state. Congress did not act immediately, owing in part to mixed signals from Floridians on both sides of the annexation issue. The tipping point came in 1845 when the governor, territorial delegate to Congress, and legislative council all lined up behind a pro-annexation stance. Southern anxieties over the prospect of Iowa being admitted to the Union as a free state played no small part in prodding Florida's annexation. Congress passed a bill admitting both Iowa and Florida as states, which President John Tyler signed on March 3, 1845.

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program

Listen: The Assorted Selections Program