Florida During World War II

Contents

A Brief History

Student Resources

Primary Source Sets

Teacher Resources

World War II was a transformative moment for Florida. About 248,000 Floridian men and women served in the armed forces. Dozens of military bases were established or expanded in the state. They hosted hundreds of thousands of military recruits who came to train for their roles in the war. Many of these people returned to Florida after the war as visitors or even new residents, fueling a major population boom for the Sunshine State.

Florida’s civilian population had an important role to play as well. They volunteered for civil defense tasks like patrolling the coastline and watching the skies for enemy aircraft. Families conserved food and collected scrap metal and other materials to be recycled into goods for the war effort. Agriculture became more important than ever, as did the state’s shipbuilding industry.

This unit uses primary sources from the collections of the State Library and Archives of Florida to introduce major themes, events and individuals related to Florida’s role in World War II.

Preparing for War

World War II got underway in Europe and Asia in the 1930s, years before the United States became involved. Americans debated whether the United States should have a role in the war. Some believed the United States ought to stay neutral and let the Asian and European nations sort out their own problems. Others, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt, believed the outcome of the war would seriously affect America’s security. He argued that the United States should build up its defenses at home and help the Allies—Great Britain and France—without actually getting into the war.

Floridians were divided on this issue. Governor Fred Cone and the state’s representatives in Congress received many letters and telegrams favoring both sides of the debate. Some citizens believed giving even limited help to Great Britain and France would drag the United States into the war. “This ‘short-of-war’ business is a snare and a delusion,” one Miami editorial read, “because it leads us step by step nearer and nearer to actual participation in the war.”

Other citizens sided with President Roosevelt’s view—that the United States’ best chance to stay out of the war was to help the Allies. Sending American tanks and ships and planes might prevent the need to send American soldiers. “The choice is plain,” wrote the editor of the Fort Myers News-Press in 1940. “If we think we may have to fight Hitler then we should join the British at once, either by active steps short of war or all the way… to keep invasion away if that be possible or give us the time we shall need to resist it successfully.” Governor Fred Cone and U.S. Senator Claude Pepper both actively supported this outlook.

Florida Answers the Call to Serve

As the threat of war increased, the United States took steps to prepare. National Guard units, including nearly 4,000 troops from Florida, were called into service. In 1940, Congress and President Roosevelt approved the first-ever peacetime draft. Men between the ages of 21 and 45 had to register for military service.

On December 7, 1941, Japanese planes attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Germany chose this moment to declare war against the United States as well. With America now at war in both Europe and Asia, many more people volunteered to join the military. Between 1940 and 1947, more than 250,000 Floridians served in the armed forces.

And it wasn't just men. Women volunteered for military service also. Some joined the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC) and served as mechanics, telephone operators, postal clerks, drivers and in other support roles. The Navy established the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) in 1942. Much like their WAAC counterparts, WAVES staffed naval stations around the country, working in health care, storekeeping, communications and clerical jobs. There were also female aviators, called the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs). Jacqueline Cochran, a Florida native, was the first director of this program. The WASPs took over non-combat flying jobs, especially ferrying aircraft between air bases as needed. This freed up male pilots for combat missions.

The military was still segregated at this time. African Americans were drafted and encouraged to enlist in the armed forces, but they were assigned to all-black units, lived in separate quarters and served almost exclusively in non-combat support roles like cooking, driving, cleaning and moving supplies from place to place. By the end of the war, many more African Americans were serving in combat roles, even as fighter pilots, but only after black leaders pressured the Roosevelt administration to order the changes. Floridians Mary McLeod Bethune and A. Philip Randolph were both strong advocates for racial equality in the military.

Training the Military

World War II forced the United States to build up its military to an enormous size very quickly. More than 170 military installations were established in Florida during the war, including major bases like Camp Blanding, Camp Gordon Johnston and the naval air stations at Pensacola and Jacksonville. The warm climate meant troops could practice their maneuvers outdoors at any time during the year. There was also plenty of open, unoccupied space that could be turned into runways, bombing ranges and other facilities.

Camp Blanding, located in Clay County, was so large that it comprised the fourth largest city in the state during the war with 55,000 inhabitants. There were also dozens of smaller airfields and special training centers all around the state, even in the Everglades.

Women service members also trained in Florida. Mary McLeod Bethune—founder of Bethune-Cookman College and an advisor to President Roosevelt on African American affairs—served on the WAAC advisory board. She helped influence the decision to locate one of the WAAC training centers at Daytona Beach. Around 20,000 women trained at the center during the war.

The federal government spent millions of dollars training soldiers in Florida. In Miami and Miami Beach, for example, the military contracted with about 300 hotels to provide housing for more than 78,000 troops. Service members also spent money in the communities where they were stationed. Family members of these troops often visited the state, which brought in even more revenue. This more than made up for the money Florida lost as wartime restrictions reduced the normal flow of tourists.

All in for Victory

American civilians took steps to support the war effort at home. One of the most important tasks was to conserve materials that were needed for fighting, especially metal, paper, construction supplies, rubber and food.

In 1942, the federal government began rationing critical necessities for the war effort, starting with rubber. Within a year, gasoline, automobiles, bicycles, many foods, shoes and even typewriters were being rationed. The government issued every man, woman and child a series of ration books with stamps that had to be turned in with money to buy restricted items. If a person ran out of stamps for a rationed item, he could not legally buy it, even if he had the money.

The government encouraged civilians to grow some of their own fruits and vegetables. Government officials and volunteers gave out lots of advice, tools and supplies for growing “victory gardens” and preserving the produce by canning it. Thousands of Floridians participated. Some local governments helped by allowing citizens to grow crops on vacant lots, or establishing community canneries where people could bring in their produce and preserve it.

Civilians also helped conserve important materials like steel, aluminum, rubber and paper by recycling. All people, even young children, were encouraged to collect scraps of these materials and turn them in to be recycled. One statewide drive in 1942, for example, produced 30 million tons of scrap metal, all collected by kids. The students who collected the most scrap metal were rewarded with a trip to Mobile, Alabama to christen the liberty ship Colin Kelly.

This effort required a lot of coordination and planning. In Florida, there was a State Defense Council and more than 130 local defense councils. Volunteers working for the local councils handled all kinds of tasks like selling war bonds, organizing carpools to save fuel, child care for working mothers, sharing information about rationing rules, and planting community victory gardens.

Defending Florida

As the name suggests, local defense councils also had a more pressing job—to prepare their communities for potential enemy attacks. Florida's position between the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean made this especially important because of the threat from German submarines and the possibility of air raids or sabotage.

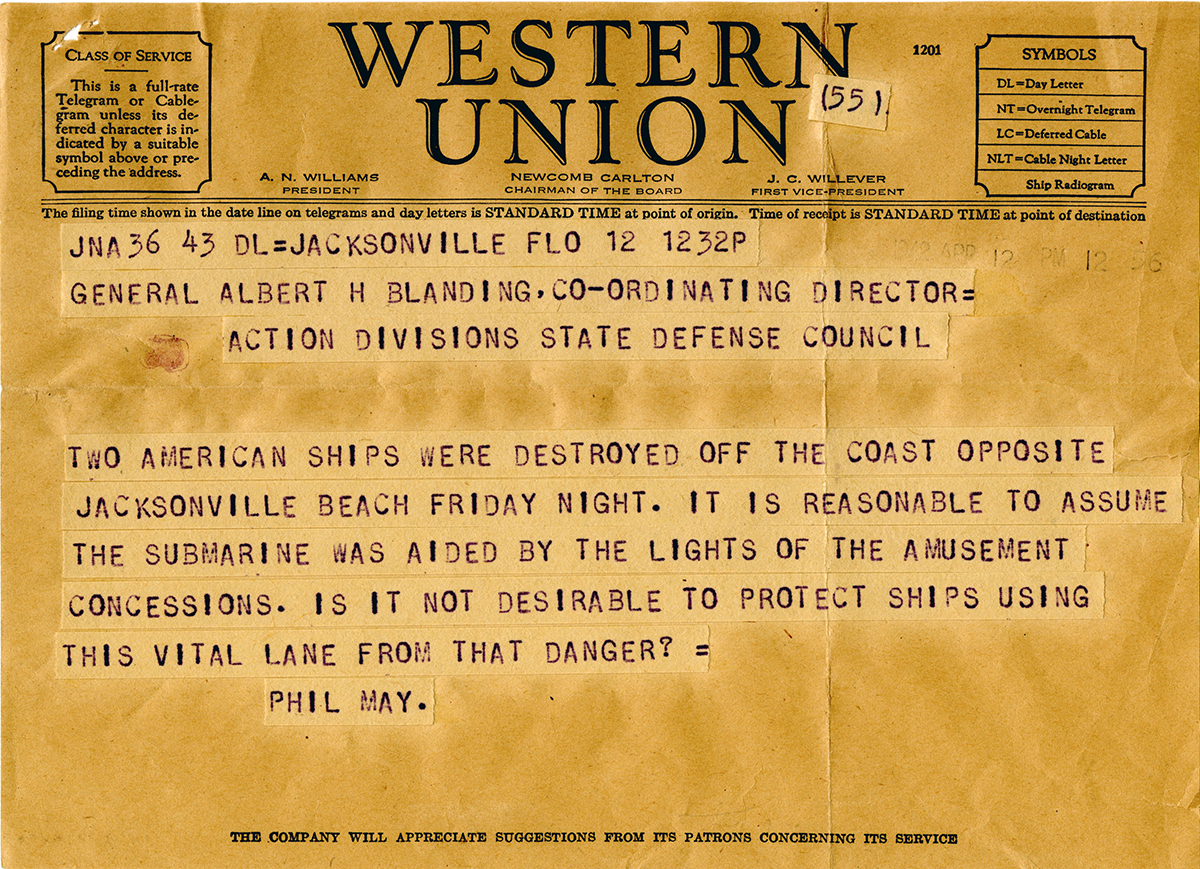

Defense councils along the Florida coast organized blackouts to make it harder for enemy submarines to attack Allied ships at night. The dark silhouettes of ships were easy to see against a background of bright lights, but with all the lights turned off it was harder for enemy submarines to know where they should fire their torpedoes. Even with the blackouts, German submarines still sank 24 ships off the Florida coast during the war.

Watching for enemy aircraft was another important defense task. Men and women of all ages—even children—volunteered their time to sit atop roofs, watchtowers and other structures to look for airplanes. Ground observers, as they were called, were supposed to identify each plane they saw and report them by telephone to a control center, which would use the information to track the plane's movement. In an age when radar was only just coming into use, this was a vital job.

Like the military, civilian defense councils were segregated. So, for example, a local defense council sometimes had two completely separate health and safety committees, one working only with white citizens, the other only black citizens.

Producing for the War Effort

Citrus fruits and other agricultural products were Florida's main exports during the war. From 1942 to 1945, the federal government bought virtually all of the fruit grown in Florida for military purposes. Two Florida scientists invented a new method for concentrating orange juice, which made it easier to transport and preserve. The high demand for this new product and traditional canned and fresh citrus led to a boom in production. During the 1945-46 harvest season, Florida's citrus farmers sold 29 million more boxes of citrus than they did during the 1940-41 season.

Finding enough labor to tend and harvest these booming crops was a serious wartime problem. Many of the men who typically worked these jobs either left to join the military or took higher-paying jobs vacated by other men. Federal and state agencies created programs to recruit women and even school-age students to work on farms, but it wasn't enough. The federal government ended up importing thousands of guest workers from the Bahamas and Jamaica to ease the labor shortage. Prisoners of war were also recruited in some cases.

Shipbuilding was Florida's biggest industry outside of agriculture. Large shipyards at Jacksonville, Tampa, Panama City and Pensacola hired thousands of workers to build the ships needed for the war effort. Panama City's Wainwright Company alone constructed 108 ships, employing about 15,000 workers.

With so many men in the military, women stepped in to do many of the jobs that men typically would have done before the war. They drove buses, welded ship parts, operated heavy machinery and ran a wide variety of businesses.

The Double-V Victory

Many African Americans served in the military, defense industries and volunteer efforts on the homefront. And they did it despite the ongoing reality of segregation and racial discrimination. The irony of the situation was obvious to many black Americans—the United States was fighting overseas to end tyranny and restore democracy, and yet racial prejudice was still commonplace at home.

Still, black leaders like Mary McLeod Bethune and FAMU president J.R.E. Lee encouraged African American Floridians to give their full support to the war effort. They believed that if black Americans demonstrated their loyalty, patriotism and willingness to serve the common good during the war, it would help people see the need to end racial discrimination and segregation. During the war, this idea came to be called the “double-V victory.” The hope was that Americans would achieve two victories in World War II—victories over both the Axis Powers abroad and racial injustice on the homefront.

These hopes were only partly fulfilled. The federal government took a few steps toward racial equality, including executive orders aimed at ending discrimination in federally funded defense industries and desegregating the military. Racial prejudice and segregation in schools and other public institutions continued, however.

After the War

News of Japan's surrender reached Florida just after 7:00 p.m. on August 14, 1945. Virtually the entire state erupted into a frenzy of celebration unlike anything in the history of Florida.

The Allies had won the war, but only at a high cost. More than 418,000 American citizens – soldiers and civilians – lost their lives as a result of World War II. Many more people received injuries that affected them for the rest of their lives.

World War II was the starting point for a major economic growth spurt in Florida. The population grew by 46 percent during the 1940s, mainly because of the war and its effects. Many soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen and nurses who trained or served in Florida later returned to the state as visitors or new residents and helped fuel the postwar economic boom.

The GI Bill was a federal benefit program for veterans returning from World War II. One of the benefits it offered was help with college tuition, and many Florida veterans took advantage of this. The University of Florida, the state's only public university for white men at that time, lacked the space to serve all of the veterans who wanted to attend. The Legislature came up with a temporary solution by authorizing a branch of the university in Tallahassee at the Florida State College for Women (FSCW). In 1947, the Legislature made FSCW co-educational, meaning both men and women could attend. The institution was renamed Florida State University to reflect this change.

Listen: The Blues Program

Listen: The Blues Program